You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping“I don’t understand this book.” A friend stated rather huffily, giving back the thick embossed book I lent to him. “It has no words.”

“What don’t you understand about it? Didn’t you read it?” I asked, baffled. To me, The Arrival made more sense than any literary or graphic novel I had read in a long time. There is a sequential, visual logic to it that justifies its semantic silence.

“I tried to,” he says, now hesitant. “But I think I was reading it wrong.” I give him back the book and tell him to take his time. I’ve seen many people take the book from my hands, flip through it in two seconds and say “that was interesting”, not really grasping the profound meaning behind the images when pored over in chronological order. I know what they’re all looking for: the words. But there aren’t any in The Arrival, not a single identifiable letter.

“I tried to,” he says, now hesitant. “But I think I was reading it wrong.” I give him back the book and tell him to take his time. I’ve seen many people take the book from my hands, flip through it in two seconds and say “that was interesting”, not really grasping the profound meaning behind the images when pored over in chronological order. I know what they’re all looking for: the words. But there aren’t any in The Arrival, not a single identifiable letter.

“There’s always a set time with words, with the way you’re reading them from left to right. Looking at pictures, however, is a little like map-reading. There isn’t an end or a beginning,” Shaun Tan tells his audience at his inaugural launch event in Waterstone’s. “I find that when you pair text with image, people will always believe the captions first instead of looking at the images.”

So begins almost two hours of conversation; for all of the hauntingly sparse, emotionally loaded words/images in his works, Shaun Tan is chatty and warm: he delivers his anecdotal speeches with eloquence and humour.

“From an early age, I loved words. I figured out how to avoid being bullied at school just because I was good with words. At telling jokes.”

He’s worried about being mistaken for a fine arts academic though. “I love art – but I hate not understanding a lot of it. I do like going to galleries but then I’ll see a painting that requires a PhD to fully understand it. That’s not what I want to achieve in my own work. I want it to be universally accessible; that’s why The Arrival doesn’t have any words in it. Even when I do use words in my work, they’re pared down. I wanted someone without any formal education to be able to understand it as well, because immigration is such a universal theme.”

Born into a Chinese family in Australia, Shaun and his brother grew up as second generation immigrants in Perth. Shaun recalls his fondness for science fiction and writing from a very early age. “I kept writing all these Bradbury-esque short stories at the age of 14 or 15 that were all rejected by the magazines I sent them to. Then I started tacking on illustrations to these stories, hoping that it would get them noticed a bit more. What happened instead was that the publishers would still reject my stories but then ask me to illustrate other people’s stories.”

From there, Shaun went on to illustrate various science fiction stories throughout his college years and then naturally progressed to writing and illustrating his own books post graduation. Since then, he’s won an Oscar for his animated short The Lost Thing and several literary awards. His books could be called ‘children’s books’ but they’re not simply books for children. The strongest case in point for this is The Red Tree, a book showing a series of paintings presenting a dark fragmented journey through a strange alien world. The book is widely loved in Australia and is used by psychotherapists and psychiatrists.

“Creativity is a kind of depression in itself,” Shaun says. “But the worst thing about it was that it felt like such a wasteful experience and I wanted to make something out of it. The Red Leaf is about loneliness and I think everyone, child or adult, can identify with that.” It also helps that Shaun views children as ‘people from another culture’ rather than underdeveloped adults.

The Arrival is almost synaesthetic in its deliverance; we hear things, words, although we are only using our sense of sight. Shaun Tan has seemingly broken into another dimension – neither literature nor comic – that allows for an awareness of language when there is none. He has taken the spatial freedom in the art form of comics (it’s clear that each box, each double page spread, has been carefully thought out in what Mikhail Bahktin calls ‘the chonotope’: how space-time relation integrates to create another language) and paired it with associative symbolist-semantics (we see a picture of hands touching, a symbol for love and reassurance). Sometimes it takes two pages for the protagonist to land on the ground; other times a single silent image expresses an entire wealth of emotion.

The Arrival is almost synaesthetic in its deliverance; we hear things, words, although we are only using our sense of sight. Shaun Tan has seemingly broken into another dimension – neither literature nor comic – that allows for an awareness of language when there is none. He has taken the spatial freedom in the art form of comics (it’s clear that each box, each double page spread, has been carefully thought out in what Mikhail Bahktin calls ‘the chonotope’: how space-time relation integrates to create another language) and paired it with associative symbolist-semantics (we see a picture of hands touching, a symbol for love and reassurance). Sometimes it takes two pages for the protagonist to land on the ground; other times a single silent image expresses an entire wealth of emotion.

Shaun Tan’s inexperience with comics and lack of formal art training is unique for an artist of his status and talent. He’s a novice, excited by the journey he’s taking in discovering new work. “I was in this bookstore in Perth, and saw this book I had never heard of before that had been published in a special edition, and picked it up,” he chuckles to himself. “It was The Snowman.” He makes comparisons between The Snowman and a few of his novels; a recurrent theme in his works is discovery, finding the unusual in the ordinary.

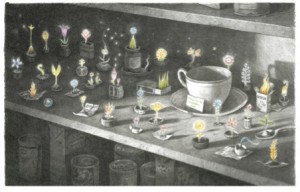

“There’s a bit in The Snowman that really resonated with me, because it was basically what I had done in a lot of my work. The snowman goes into the house and becomes fascinated with appliances what we take for granted: the fridge, the washing machine. There’s a scene in Eric which is exactly like that.” Shaun shows us the picture. “For example, here he’s wondering if the drain is meant to look like a flower.”

Eric questions various ordinary things he finds in the house

The audience laughs and Shaun confesses: “Actually, that’s what I thought when I was little, that drains were supposed to look like flowers.” Eric is a little exchange student/thing who comes to stay with an Australian family for a while. Shaun wrote the story as a response to his own experience with a Finnish exchange student who came to stay with his family a while ago. “We were always worrying about whether he was having a good time or not. But then when we went to visit him in Finland a year later, he showed such enthusiasm about the trip, enthusiasm that we really hadn’t seen in him during the trip. So maybe I thought it was because he couldn’t express himself properly, that he was just so overwhelmed and needed time away from us to collect his thoughts.”

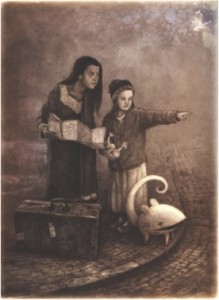

Shaun shows us the last page of Eric, where Eric himself has left his host family (without saying goodbye, no emotional finale: he just sails out the window unnoticed) and they’ve gone to look for him in the kitchen, where he likes to sleep. They find this:

It’s a faultless ending. “Endings are the easiest part of creating a book for me.” Shaun says. The evening ends with him signing everyone’s book, pleasant as ever after a long day of talks and signings. Even his ‘signature’ is not a signature: it’s a symbolic stamp plus a little drawing of the animal he created in The Arrival. Shaun takes his time talking to his audience, from the 70 year old man in front of me to the 10 year old boy behind. It’s refreshing to see that, despite the Oscar and the awards and the acclaim, he’s still in touch with what makes his novels so poignant: human relationships.

Ysabelle Cheung