You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

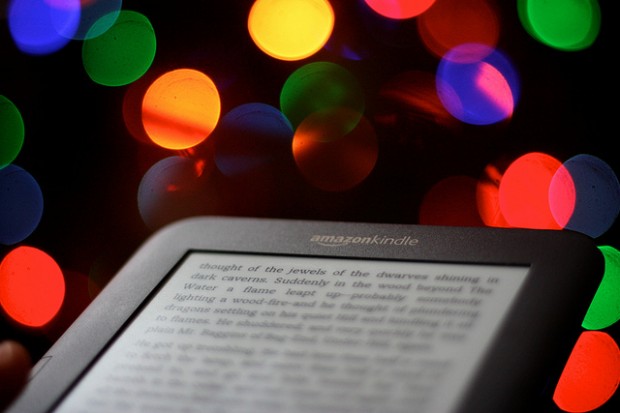

My favourite present this Christmas was a Kindle.

No, really. I’ve come a long way since the moment I announced, a year ago, that while some people might find a use for an e-reader, I could never be persuaded to make the move away from real books.

You know when you remember a past statement and just wish you could put it back into your mouth and swallow it for ever? Yes. That turns out to have been one of those.

I’m a serious reader. My addiction is incurable. The walls of my flat are lined with books, so many of them that they have overflowed their shelves and now stand in towering installations around the living room. It’s a weird week when I don’t read at least one book, maybe two, probably three. So I should be championing the importance of the printed word and denouncing those dangerous e-book pretenders, right? Well, that’s what I used to think.

But then, sometime during 2012, my opinion changed. Maybe it was the fact that so many of the other people speaking out in favour of print books were doing it in a way that I can only describe as embarrassing, grading to insane. First there was the (serendipitously titled) Slate article, ‘Out of Touch’, which argued that

If books are essentially vertebral, contributing to our sense of human uniqueness that depends upon bodily uprightness, digital texts are more like invertebrates, subject to the laws of horizontal gene transfer and nonlocal regeneration. Like jellyfish or hydra polyps, they always elude our grasp in some fundamental sense.

This pretentious piece overlooks a pretty obvious fact that I couldn’t help but notice – that e-readers are actually physical objects. When you read with one, you may not be holding a sheaf of paper, but you’re still holding an item with words on it and taking those words into your brain. The same words, incidentally, as you would take in with a paper book.

Not that fanatical e-book detractors will admit that. They behave as though the act of passing precious words through an electronic device somehow makes them less valuable. Last month I went to an event at which several of the UK’s most prominent critics talked about e-books and e-readers as though a Kindle had personally come into their houses and killed their families. “They’re terrible!” cried one. “They’re ruining the country’s reading culture!” complained another. A woman in the audience nodded in agreement. She, she told the room, feared for the children who were unlucky enough to grow up using these dreadful devices. “But how many of you have one?” asked the first critic suspiciously. There was a pause, and then three quarters of the room put up their hands. After that, the discussion became much more subdued.

If even these snobs were hiding secret e-reading habits, the format must, I thought to myself, have something to it. After all, what could really be so bad about the act of e-reading? The words are the same, and it’s the words that really matter. Paper is lovely to touch, covers are beautiful to look at and there’s a special acquisitive joy about owning a physical object that any bookworm will recognise immediately, but a book is made up of words, and that’s what an e-reader offers: the chance to get to grips with those words, just in a different medium.

And what e-books lack in packaging they more than make up in additional features. Instead of just reading you can also listen to audio, watch a video or look at photographs to enhance your experience of the text. Random House’s recent A Clockwork Orange app includes interviews with critics and a scan of the original manuscript. Looking at it from this point of view, the idea of owning an e-reader suddenly seemed extremely attractive to me.

So now I’ve got one. What’s my verdict?

You may be surprised to hear it, but the words still look like words. They still go together to make stories, and those stories are just as good, or as bad, as they would have been if I’d been touching pages instead of my rather fancy leather Kindle cover. Even the technical issues I was worried about turn out not to matter: I’m surprised by how similar flicking from screen to screen feels to the physical turning the page motion I’m used to, and I realise that what I found less immersive about reading on a computer was its ability to switch between multiple procrastination methods rather than anything about the scrolling text. Reading a book on my Kindle still feels like I’m, well, reading a book. The medium alone can’t make a reading experience invalid. I haven’t ‘read’ Trilby, I’ve read it, and there’s nothing any nay-sayer can do that’ll convince me otherwise.

Has my Kindle put me off physical books? Since I went out last week and bought seven newly-released paperbacks, I don’t think so. On the contrary, it’s given me access to an additional treasure trove of out-of-copyright, and therefore free, classics. As a fan of eighteenth century and Victorian literature, this is a huge attraction: my e-reader has given me the ability to get my hands on books that (aside from fortuitous discoveries in second-hand bookshops) simply don’t exist for me to buy in physical format.

Then there’s the weight issue: I can read Little Dorritt on the train without putting out my shoulder trying to haul a physical copy of it around in my bag. And if I find a title that I fall in love with and know that I want to read again and again in future – well, I’ll buy a beautiful physical copy to keep on my shelf. Conversely, I no longer have to worry about wearing out my favourite copy of an old and much-loved novel. Instead, I’ll just buy the e-version so I can read it on holiday while it’s still sitting safely on its shelf – the literary equivalent of having my cake and eating it too.

Of course, I need to point out that the e-book is not a trouble-free product. There are e-book detractors – and these are the ones that I do listen to – who point out their concerns about low pricing models. They also (with good reason) remind digital fanatics that the current e-book licensing method means that readers do not own the e-books that they buy. They are merely renting them from the distributor, a rental that can be brought to an end at the distributor’s discretion.

But are those things enough to damn e-books and e-readers? Of course not. And are people who predict the paper book’s demise correct? I don’t think so either. E-books are not paper book replacements, nor are they really being marketed as such. They should be seen as a handy alternative, a useful add-on that’s more likely to improve and expand reading culture rather than kill it off. E-books can do things that print books can’t, and vice versa – but what stays the same, no matter the medium, are the words themselves. And aren’t those words what we’re all here for?

About Robin Stevens

Robin started out writing literary features for Litro and joined the team in November 2012. She is from Oxford by way of California, and she recently completed an English Literature MA at King's College, London. Her dissertation was on crime fiction, so she can now officially refer to herself as an expert in murder (she's not sure whether she should be proud of that). Robin reviews books for The Bookbag and on her own personal blog, redbreastedbird.blogspot.co.uk. She also writes children's novels. Luckily, she believes that you can never have too many books in your life.

Also got my Kindle as a present once and can’t get enough of it since then. It’s got so much potential these ebook. Although I guess now they are getting beaten by tablets (and to be honest I’m also thiking of getting one).

I guess sometimes I miss the feeling of holding a regular book in paper, cause I like the covers and smell…but I’m trying now to at least spice up my Kindle too with cases. Got quite a funky one from ‘caseable’ so I’m happy :-)

I’ve got an absolutely beautiful leather cover! It almost makes my Kindle as nice to touch as a paper book. I do keep trying to check the front of it to see what I’m reading, though…

@KimBru49 Haven’t read this one yet: https://t.co/9ArKxG0z. But it sounds like what happened to me. I started reading the classics.