You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

In Western thought, literature has often been separated from politics. Plato founded this tradition when he famously banished the poet from the city with the resounding words, “Not pleasure and pain, but law and reason shall rule in our state.” According to Plato the poet is, at best, politically ignorant and untried–he imagines asking Homer “tell us which state has been better governed because of you?–and at worst, a spurious manipulator of emotions threatening the polis. Much, much later, in the 19th century, the Aesthetics would also separate art and politics, but for diametrically opposed reasons: rather than wishing to protect the polis from the irrational or morally degenerate artist, they wished to protect the artist, to free him from the shackles, compromises and conventions of social-political responsibility. ‘Art for art’s sake’ became the well-known aphorism of their movement, a war cry for the free pursuit of the beautiful and conceptual that echoed and continues to echo in the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century.

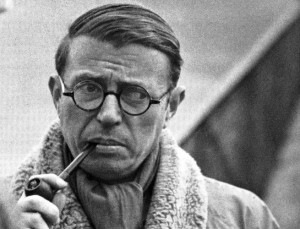

One of the most famous contestations to the separation of literature and politics–and critique of the modernist desire to rise above the fray of history–is articulated by French philosopher and writer Jean-Paul Sartre (photo above). In the late 1940s, after witnessing the spread of fascism and two World Wars, Sartre publishes What is Literature? Described by Susan Sontag as “the most intelligent version of the theory of literature’s obligation to be socially committed,” Sartre not only argues that every act of writing is political, but champions literature’s ability to awaken the critical faculties and social consciousness of its readers. In his discussion of littérature engagée, or ‘committed literature,’ he posits that good literature engages the free individuality of the reader, urging them towards self-reflection and change.

Interestingly, as demanding of literature as he might be, Sartre absolves one form of literary production from political commitment on the basis of its relationship to language: poetry. According to Sartre, poetry’s use of language is a-social, a-referential, self-enclosed and even inhuman, completely different from the “essentially, utilitarian” nature of prose that treats words as “loaded pistols” to fire into the world. Sartre says the poet turns language “inside out,” making words themselves, rather than the world, the objects of contemplation. In the 1930s, partly trying to protect the ideological purity of poetry, partly commenting on its nature, W.H. Auden pithily says, “poetry makes nothing happen.”

And yet, poetry continues to rendezvous with politics. Three movements or ‘genres’ of poetry–bearing in mind these are inorganic classificatory systems– that put social commitment at the heart of their aesthetic work are the American Language poets, “poetry of witness” and Documentary Poetics. The Language Poets were a group of avant-garde, theoretically sophisticated poets in the 1960s and 70s who were interested in how poetry might be used to explore the political ramifications of language. “Poetry of witness,” a term coined by the poet Carolyn Forché, describes poetry written in exile, war or imprisonment. Forché argues the witness poet defies the comfortable categories of political/private, social/individual by re-integrating the individual voice back into the social. And Documentary Poetics is what poet Mark Nowak describes as poetry aspiring to “a more objective third person documentarian tendency.” To give a sense of what Documentary Poetics is in practice, in his collage-montage work Coal Mountain Elementary he combines the culled language of miners and mine rescue crews with photographs to both educate and testify to their experience. Widely varying in their ambitions, processes and products, these movements are a few examples that nonethless ask us to reconsider: Why use poetry? Could there be something about poetic form that actually makes it a powerful tool for social change?

If anything connects these three different movements in their use of poetry, it’s paradoxically what they don’t share. Or rather, they share the flexibility of poetry. A form that is a non-form. Poetry can be contentedly free and deviated from normal speech unlike prose, which generally still has to respect a certain degree of convention. Sartre argues in What is Literature? that even prose works that defy these normal patterns of speech are not changing the nature of prose, but simply adopting poetic pretensions. The poetic and the prosaic could be construed as modalities of greater or lesser verbal freedom.

To summarize the political implications of freed, poetic speech, I turn to Juan Goytisolo, Spain’s arguably greatest living writer, who says: ‘the negation of an intellectually oppressive system necessarily begins with the negation of its semantic structure.’ In Goytisolo’s own novel Reivindicación del conde don Julián–which could perhaps more accurately be described as a prose-poem–he battles the oppressive system of Francoism by breaking down language into disconnected fragments separated by colons. He parodies, de-contextualizes and juxtaposes different registers of speech to expose the ideology hiding behind the naturalized rhetoric of the regime. His tactic is similar to the work of the Language Poets not only in that it looks to dredge up the political consequences of language, but in how it alters the relationship, inevitably a political one, between reader and writer. If poetry is freed language, the poetic encounter is also a freed reading experience. The reader isn’t directed as she is in prose. Without becoming too enamored of postmodern fetish concepts like ‘ambiguity,’ ‘possibility’ and ‘open-endedness,’ the reader has to make her way herself with her own judgment as guide.

I love Sartre’s enthusiasm and idealism, but I find his exclusion of poetry from politics hasty. Certainly poetry doesn’t need to be committed, but it can be. In an age which thinks all speech is politically, socially or ideologically implicated in some form, turning our attention to the density and opacity of language that only pretends to be translucent could be one of the greatest political acts of all, a way of giving the reader tools for their own political freedom. At the very least, what the resurgence of poetry of witness and Documentary Poetics tells us is that the politics/poetry debate initiated by Plato is far from over.

About Haley Stewart

Haley Stewart is from Portland, Oregon and a graduate of Williams College in Massachusetts. Currently, she's continuing her Comparative Literature studies at the University of Cambridge. She's a lover of prose and poetry alike, a fluent Spanish speaker, trying to learn French and an avid traveler.