You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingThis book is about Michael Stipe’s shyness, Jarvis Cocker’s brown-cord genius and Pete Burns’ left testicle peeking out from his leotard for the entire duration of a gig he did at the Palais (in the “Bowie’s Nose” chapter: “The front row was in stitches, man. Burns was oblivious.” An apt metaphor for the rise and fall of Britpop perchance?). But mostly this book is about Flamingoes, a band active during Britpop’s high-watermark years in the nineteen-nineties, and a Proustian scratch ’n’ sniff tour through their musical influences down the decades.

This book is a veritable who’s who of the alternative music scene of the nineteen-seventies up to the late nineties, when, according to the author, James Cook, it all fractured into subgenres like a brick through a plate-glass window or a “Les Paul through a Marshall stack.” Apparently it was all Suede’s fault. Suede: “an amalgamation of the Smiths and David Bowie… They had successfully repackaged the seventies for the nineties… Glam, refracted through an indie sensibility.” This book is best read in front of a full-length mirror wearing 28″-waist white Levi’s, a bottle-green Brett Anderson blouse and lashings of eyeliner. If not, you’re obviously one of them.

I’d never heard as much as one note from this band before reading this book, and I still haven’t managed to Google a sample, but the fact is there’s no need, you’re in safe hands, because from the range of influences cited and the writing within, it’s quite a simple task to imagine their sound. At this stage to actually hear one of their songs through the build-up of wax I have would be a crushing disappointment. The music could never do justice to what I’ve already seen and heard. However, reviewing this book seems like a Dick Dastardly and Mutley laugh of a thing to do after reading the ideas sausage-sizzling between its covers.

Like Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher before him, the author posits that the future has been cancelled. It’s over. Go home. Crawl to the coal-shed under the stairs, get into the foetal position and die, motherfunkster, die. Obviously it’s all Thatcher’s fault but in alt-music terms the author points the finger squarely at Britpop, the period when it all seemed to go kerboom bang-a-bong: “Thus the Britpop moment was when the injunction to generate new ideas and push upward into unexplored territory, was finally abandoned.” Which makes me feel like a traitor to all our futures, musical or otherwise, by reviewing a book that had already been written and looks so often to the past. It feels wrong. And it’s all the author’s fault, because what he argues cogently throughout holds true. For me at least. You’d really want to be reviewing books that haven’t been written yet, books that are mere concepts, twinkles in the milkman’s eye, to be getting anywhere ahead of yourself. Be tomorrow here now. Because I’ve seen the future and the future of music is silence – and conceptual. No instruments. No craft. No tuning. No keys. Unspoken word perhaps. But maybe not even that. Five negatives make a positive. Zilch is the new year zero.

In the age of austerity, music is permanently superglued to the hands of the privileged, no quarter or solvent given. The author posits early in this book that in the future “Lennon, Page, Bowie and Ferry, who all trained as artists, might be painters, or sculptors, conceptualists, Mike Scott a poet or a novelist. Possibly some wouldn’t be artists at all. Richie Edwards might be an academic.” Not musicians. Definitely not musicians. Not in an X-Factor-Britain-America-Europe’s-Got-Talent new world order. Hardly anyone can be a functioning musician these days. It’s not feasible anymore. The exception proving the rule. The author points out the genius of Jarvis Cocker’s song “Disco 2000”, in which he managed to look backwards and forwards at the same time without pulling a muscle or ripping his trousers up the arse. “Nowadays it’s uncanny to come across the yellowed spine of ‘Disco 2000’ on the CD shelf, the future already part of the past.” But should we always be belting off like hares into the horizon? is probably the main question this backwards and forwards narrative poses constantly throughout its chapters.

Simon Gilbert was a drummer with Flamingoes who went on to play with Suede. On their first single, “The Drowners”, Simon’s “Pretty Vacant” drum solo intro was “there to identify his allegiance to punk (and also appropriately enough Adam Ant’s ‘Press Darlings’)”. A nice segue into the past before roaring full steam ahead into outer space with Bernard Butler’s “massively slurred A-major chord”. A time of “schizo-simultaneity”, as Mark Fisher might say, when past, present and future are conflated and compressed together in a retro yet modernist blender.

The author, James, and his twin brother and fellow band member, Jude, moved bravely from the Hertfordshire town of Hitchin, where they grew up, to London in the eighties to make it as a band. It took a fair whack of blood, sweat, tears and time to get to where they eventually ended up, making a decent album in the mid-nineties before the future closed in on them like a noose. Like it did on us all. Luckily, as stated above, the future was cancelled shortly thereafter, so complete strangulation did not occur, although damage was done to the throat and windpipe areas, rope hanging loosely around the neck still. Each chapter and memory song we gallop through in this book is a veritable treasure trove of information and analysis on the alt-music scene that held their hands, heads and hearts through almost everything they went through. There’s a sharply dressed madeleine on every page if you want to get all Proustian about it. But don’t blame me if your stomach bloats and trouser-button pops into someone’s eye by the time you get to the end of the book, overindulged.

The two brothers got into Cambridge University but didn’t take up the offer, plumping instead to concentrate on making it as a band in London – death or glory. The belief and determination of the Cook twins is truly astonishing. Who has the balls to do such a thing at that age? Turn down Cambridge for indie. To make such a momentous decision. Who? Obviously excluding Pete Burns, who probably did a whole European tour with his left testicle hanging out of his leotard, while giving everyone the nail-varnished finger in purple. Well it didn’t work the first night man, so I’m keeping it out there till the end of the tour, so that it can keep on not working for the next six months.

A line on the first page of chapter one propelled me right into the action like a flicked elastic band. The author writes about the stark choices facing the Cook brothers: “…Proper job versus an insane artistic project that has become increasingly indefensible to friends, girlfriends and every other member of the family.” Amen to that. One of the factors in deciding to turn Cambridge University down was that the author “had an uneasy feeling that Cambridge would be bad for the street cred. All the musicians that mattered to me were from ordinary backgrounds like myself. Not many had gone to university, let alone Oxford or Cambridge.” That’s how I remember the spirit of the times too, despite zombie Thatcher stalking the lands and hobgoblining the streets. All the big-hitters doing anything remotely interesting and challenging were working-class. John Lydon, Morrissey, Mark E. Smith, Richie Edwards to name a mere four. The list is endless. The biggest insult of the times was to be called a middle-class tosser. Joe Strummer went to extraordinary lengths to hide his very privileged education. It’s all so very different nowadays. I’m gonna cry thinking about it. As Owen Jones says in his book Chavs, Franz Ferdinand and a rake of other subsequent “floppy-fringe-flicking critics’ bands” feel it quite free and easy nowadays to write lyrics that threaten violence on the lives of the working classes. With absolute impunity. Portray them as animals. Thick, lazy and beyond all redemption. Chavs. Basically, racist hate speech. “You are lazy. You are thick. You are beyond all hope and you should be shot” is racist when said to a black person. And it’s racist when said to a chav too (chav – the dog-whistle racist term for the working classes nowadays). Rather than feeling obliged or morally compelled to show solidarity with the not-so-privileged like back in the indie hey hey heyday, modern bands flop their fringes in the other direction. One minute these privileged flopily-doppilies are lecturing people about racism and the next they’re being racist and writing racist anti-ordinary people lyrics with catchy tunes and winning minimalist non-glittery awards. More or less condoning racist behaviour by practising it themselves elsewhere in another format. How strange the change from vinyl to CD. They’re definitely not turning down an offer from Cambridge University to be down with the home boys righteous and proud. Like the twins from Flamingoes. I read Lol Tolhurst from The Cure’s recent biography and anytime he mentions the working classes in passing he constantly uses terms like stupid wankers, chavs and Nazi skinheads. This is The Cure – a great band. It’s all so terribly disappointing. I still want to cry. Apologies if my own left testicle, metaphorically speaking, came loose there for a while and flapped about in the breeze. I’ll tuck it back in immediately so that we can all move on and rejoin the caravan of love. Just don’t look back. Let it go.

One of the artists the author writes quite eloquently about is Mike Scott of the Waterboys. Described as a portal artist, providing you with links to important works in other art forms. “‘This is the Sea’ alludes to among others Yeats, Joyce, the nineteenth-century English artist William Strutt, and Silvia Plath. And the Waterboys, I was delighted to discover, derived from Lou Reed’s Berlin.”

Bowie. The Velvets. The Smiths. The Pogues. Joy Division all did the same. Provided doors into other books, artworks and films that are never on the syllabus of any ordinary wallpaper-covered textbook education. I hope a few current bands do the same sort of thing today, but I doubt it. Louis Walsh would definitely not like it. “You’re not allowed!” I hope I’m wrong.

There’s also a nice smattering of quirky appearances of guest stars and their appendages in this book. The author delineates David Bowie’s nose as chameleon in an early chapter. A nose that sneezed with such provocation that people are still living under the influence of its slow-drying Martian snot to this day. With multiple popup appearances by Jarvis Cocker’s song-writing prowess dressed up in “a dagger-collared red shirt, brown cord trousers, large Jackie Onassis sunglasses, Cuban heels, and a black astrakhan fur coat”. There’s plenty of arsey-flamboyance on offer to keep your fingers flicking through the pages cool as fuck-ily. Richie Edwards of the Manics also makes a striking appearance paying himself full-price into a Flamingoes gig yet still challenging every man jack and jackie in the room “to question the culture we take for granted” in ways the author is best left to explain himself.

Ian McCullough is in there too calling “All Apologies” by Nirvana the last great honest song. This book helps unpick this assertion so you can decide for yourself whether that particular Bunnyman was yanking anyone’s chain or not.

When I was growing up I could never quite remember the name of the band with yerman Page and yerman Plant in it. I blanked it out entirely every time I tried to recall it. It wasn’t until I was about thirty-five years of age that I could remember it without chin-stroking intensely for two or three minutes. Thank you very much, punk. This is where I probably don’t agree with some of the musical madeleines talking from the psychiatrist’s couch of this book. But I won’t discuss it any further as I’ve already forgotten what point I was going to make.

Finally, if there’s one band that sums up the memory songs described in this book it’s The Triffids. Everybody has that one special album. Not your favourite record but you were at some stage obsessed by it to the point of madness. For the author of Memory Songs that album was Born Sandy Devotional. The band itself seems to sum up the scene in all its earnestness. A time when music meant something and “you had to take a side, it wasn’t just another leisure option as it is now”. A glorious period when “the charts were the enemy, but we knew we had God, or at least Morrissey on our side.”

Flamingoes, a band of happy thieves, went at it full-force, 24–7, to the point of starvation and destitution, bent nose pressed up to the windowpane, snot dribbling in rivers down their chin, like that “Don’t do it” poem by Charles Bukowski, “So you want to be a writer?” They made one album that they were extremely proud of, while they were young. It was critically acclaimed. They lived the dream and I don’t mean that in any ironic sense whatsoever. They did. No tinsel.

The author’s summing up of The Triffids not only sums up this little-known Australian band but seems to sum up the entire culture and philosophy of the times, the power of creativity, Flamingoes themselves, and whatever kitchen sink you’re having yourself. I needn’t say any more. Pass the hankie.

Born Sandy Devotional till I die! (Even though my Born Sandy Devotional was Reading, Writing and Arithmetic by The Sundays.)

“The Triffids ‘failed’. They are a testament to the futility of being in a band, but also to the nobility, to do all that careful work, to commit your life to music, when so few groups are remembered.”

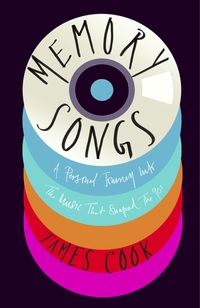

Memory Songs is published by Unbound.

About Camillus John

Camillus John was bored and braised in Dublin. He has had writing published in The Stinging Fly, RTÉ Ten, The Lonely Crowd and other such organs. You may know him from such fiction as The Woman Who Shagged Christmas, The Rise and Fall of Cinderella’s Left Testicle and, Throwing A Sausage Back and Forth for Five Minutes Without Letting it Drop. His fictionbook, Groin Frosties With Jazzy Hand – The Pervert’s Guide To Modern Fiction, and his poembook, Why The Privileged Need to Read Literature, are available to purchase from Amazon. He would also like to mention that Pats won the FAI cup in 2014 after 52 miserable years of not winning it.

It’s not very often such a well written memoir comes along with as much enthusiasm for the author’s passion but this is definitely one of a select few.

(Think Clive James’ Unreliable Memoirs’,Nick Hornby ‘Fever Pitch’ or Samantha Ellis’ How to Be A Heroine’).

The author traces both his childhood through music and film(John Barry,Bond and The Beatles) and his youth(via Led Zeppelin,Roxy Music,The Clash and more)taking us to the 1990’s not just through what he was listening to(Pulp,The Manic Street Preachers,and Nirvana) but in his band-Flamingoes-who released an album themselves-the folks at the major record label mentioned should have been kicking themselves for not signing the band and giving the music to a wider public -and toured extensively.