You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

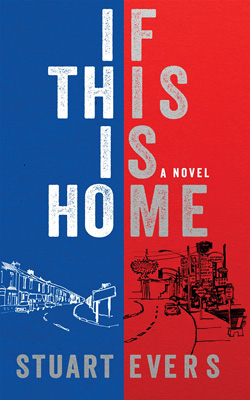

About half way through Stuart Evers’s cinematic debut, If This is Home, it becomes clear that the author has pulled one over us: this is not only an old-fashioned mystery novel, but also a postmodernist exploration of writing itself.

The novel focuses on Mark Wilkinson, a young British runaway to America, and to a past he feels compelled to return to. The crux of the book is its approach towards memory and the past – two things which are not necessarily comparable. The truth, or what composes objective reality, is what Evers is concerned with: the nature of dreams and the way storytelling can heal. In many ways, this draws comparisons with Paul Auster, particularly his novel The New York Trilogy, but Evers’ prose is less anchored than Auster’s, and often, especially in his depiction of Las Vegas, he loses a sense of time or place.

This, however, is not necessarily a criticism, as the whole of America seems to be deliberately placed on the horizon: a shimmering, partially translucent dreamscape that is never wholly occupied by Mark, the narrator, even though he has lived there for over ten years. Dreams, and their inherent unreality, are crucial to the appreciation of the novel. We first meet Mark, under the guise of Josef Pietr Novak pretending to be Mr. Jones, “selling a dream’ in that eternal city of lies, Las Vegas, to rich men who desire ‘a holiday from oneself.” Valhalla, Mark’s centre of operations, never really feels whole, but instead becomes almost maze-like as the characters make their way around it. Las Vegas, and America by proxy, is cast as a place unattainable by dreamers, a violent, grotesque reality of drugs and fakes contrasted with the childish desire to escape into a dream. Evers is at his strongest when he approaches this head on; one particular passage, via Bethany when she had ostensibly never reached those shores, captures New York wonderfully, calling it “haphazard, beautiful, maddening.”

Evers’ prose is incredibly consistent and thoroughly readable, transforming a tale which, in lesser hands, could have been depressing into something lithe, enjoyable and, occasionally, hilarious. A darkness resides within the novel, however, but it is to Evers’ credit that he balances both the reality of his story with the fictional. Saying any more would ruin the story for others.

At the heart of the novel is the youthful love story between Mark and Bethany Wilder, two people brought together by their dissatisfaction with the rainy north west of England and their shared delusions: “I love you because you share the same dreams. Because when I’m with you, I feel like a different person.” The majority of the novel is Mark’s attempt to recapture that moment, that sense of otherness provided only by a fulfilment of a dream or a love, and there is a deep knowingness presiding over most of the prose. As the reader is told, “It takes nothing for things to turn to shit.” Mark is drawn back to his hometown by a desire to see the truth, maybe even for the first time.

Evers’s minimalism is noteworthy because it is at once superficial and fast, and what it lacks in emotional punch it makes up for with its ability keep the momentum going. By the second half of the book the pages practically began to read themselves. The strength of the writing also vastly improves by the second half, which suggests the author (or, indeed, the character of Mark) is more comfortable describing his native Britain than America. In the first half, displays of certains emotions may have seemed unearned, but the second half contains some truly moving passages.

The final hundred pages also increase the complexity of the narrative, which adds a welcome layer to the story, and Evers should be congratulated for presenting a potentially alienating literary device in a wonderfully simple way. What may have appeared as a story about “how a sleepy town awoke into a modern world” reveals itself to be something else entirely. It is a story that pretends to be an example of realism, but is in fact keenly aware of the dangers of artifice. “Everything is flooding through,” Mark says during one particularly violent moment in Valhalla. And we should believe him. By the climax, Mark has become the detective of his own life and the detective, lest we forget, is the archetypal postmodern reader: “It was a notebook, a life, written in optimism: not real.”

First published 5 July 2012. Out in hardback and ebook.

Thanks to Picador for providing a review copy.

About David Whelan

David Whelan is a fiction writer and journalist based in London, England. He was formally Litro's Reviews Editor and Fleeting Magazine's Interviews Editor. Currently, he writes for Vice's food vertical, Munchies. He is one of Untitled Books's "New Voices" and his fiction has also appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Shortfire Press and Gutter Magazine, among others. He holds an MA in Creative Writing from UEA.