You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

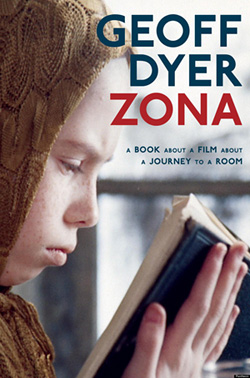

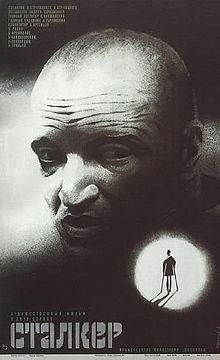

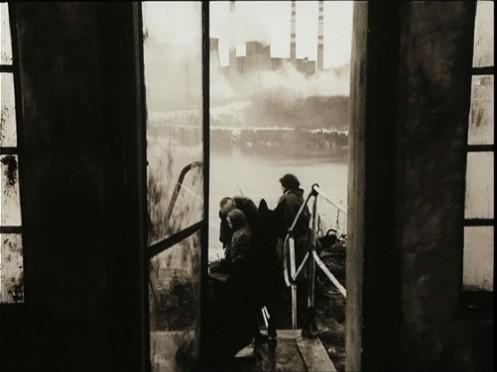

I’m on page 25 when I decide to watch Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker, to which the British author and essayist Geoff Dyer has dedicated a whole book, Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room—not a summary, but “an amplification and expansion”, taking us from scene to scene. It is not enough simply to read about it, I want to see for myself when Dyer describes Tarkovsky’s trademark long shots and the “slow contracting or expanding slightly” of the frame, “almost as if the film were breathing”. I want to hear for myself when he describes the “dripping” and “creaking and other spooky noises that are not easy to explain”, and the “sounds that emphasise the lack of other sounds”. I want to see if the barman really exhibits all the characteristics that Dyer attributes to him, and what the “sexualised fits” of the eponymous Stalker’s wife look like. Once I do, it’s like a bulb comes on—and does not blow out, unlike those in the film, set in a country with a dank and gloomy post-industrial landscape that is never named, “but wherever we are it seems that getting reliable lighting might be a problem.”

This is how I continue: I read a section from the book, then play the corresponding scenes from the film (on Youtube, which Dyer would scoff at), and then I read and watch them both alongside each other again. I make this time-consuming effort because I want to experience the book on its own merits first, though it soon becomes clear that the text takes on more meaning for me after I watch the film, and I enjoy it much more when I go back to read it again—which begs the question: can anybody enjoy Zona? In an interview with The Believer, Dyer says yes, “whether you’re a Tarkovsky nut or you’ve never even seen the film.”

My experience as someone who has never heard of or seen Stalker has been that the book and the film serve as necessary companions to each other. Just as Stalker guides Writer and Professor (we never know their names) to and through “the Zone”—created by a “meteorite” or “alien visitation” about twenty years ago and now cordoned off by barbed wire to keep people out—at the heart of which lies “the Room” where a man’s deepest wish will come true, so Dyer guides us through Stalker. If Stalker is the cinematic equivalent of Ulysses then I doubt I would have been able to get through it without Dyer’s commentary, especially since I watched it without subtitles. Then again, Dyer admits to finding the film boring when he first saw it in his twenties, so perhaps there’s hope for me yet. Because Stalker is a movie that defies our normal expectations of time—nothing really happens; there is no “climax”, no pay off. Dyer says the film can be summarised in two sentences, and I’ve already done that in the preceding paragraph. It is, very simply, a film about a journey—but what does it all mean?

Many allegories have been offered up for Stalker since its inception, which reportedly reduced Tarkovsky to “a state of fury and despair”. It has often been interpreted as a metaphor for life under Soviet communism: the grim topography, Stalker’s zek haircut resembling a Gulag inmate, the problems with electricity, and the vocabulary—the most dangerous part of the Zone is called “meat-grinder”, also the term Gulag prisoners used to refer to repressive procedures: arrests, interrogations, forced labour, unnecessary deaths, etc. As Dyer points out, however, Stalker is not only retrospective, it has also become a sort of prophecy in light of the true, tumultuous events that came after: the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, September 11.

But this is not the only way to “see” Stalker. As Dyer writes, “I am struck by the film’s reach, it’s ability to bathe events—both actual and cultural—in its projected light.” You might describe Zona as part commentary, part memoir. Dyer brings many of his life’s experiences, both profound and trivial, to bear on the film: his yet-unfulfilled desire for a threesome, his wife’s resemblance to the actress Natasha McElhone, his hankering for his missing Freitag bag—because, as Tarkovsky once said, “[T]he zone is the zone, it’s life, and as he makes his way cross it a man may break down or he may come through.” Some of Dyer’s personal anecdotes are interesting, some of them irrelevant, but as a whole it is a fresh way of commenting on the culture we consume—as Dyer explains, “Not to judge objectively or critically assess these works but to articulate their feelings about them with as much precision as possible.”

In short, Zona is a personal reaction to Stalker, and so also to the universal question of human existence: what would make us happy? Except in Stalker‘s world, your “deepest” wish—only one—could actually come true, just by stepping inside the Room. So, what do we want most? Dyer points out, “We think we have huge goals in life but actually, when it comes to it, we’ll settle quite happily for something trivial that we’ve had all the time and which made our lives bearable.” What if what we really want is not what we think we want? Worse, what if what we really want reveals a truth about ourselves we are loathed to confront? The inherent unknownness of the human heart, even to oneself, is nicely explored through the very act of travel, of life as a journey. In a long sequence in the film, Stalker, Professor and Writer are on a diesel-powered trolley rolling down a railway track, the landscape blurring past in the background. Dyer writes:

These are the faces—the expressions—of travellers anywhere […] They’re taking everything in even though they’re not sure if what they’re seeing is any different from what they’ve already seen or where they’ve just been. Frankly, they’re not entirely sure that what they’re taking in is worth taking in…

Dyer first watched Stalker when he was in his twenties, and claims that the greatest films, for him, will always be those he watched at that time of his life because he was “at the point of maximum responsiveness or aliveness, when my ability to respond to the medium was still so vulnerable and susceptible to being changed and shaped by what I was seeing”. I would agree. Even now, in my later twenties, I often have the feeling that though I hear some great songs these days, they cannot usurp the space in my memory that have been imprinted on by the songs I listened to while I was still at university, the songs that were my firsts in many ways, since our twenties are often emotionally tumultuous as we perch precariously on the cusp of adulthood. In part, it’s the nostalgia that holds you back so strongly; you want to go back to a time when you are still vibrating with possibility, when a song, or a book, or a movie can still change your life. It is harder, and more ridiculous, to say that as you get older.

It seems right, too, that someone such as Dyer, who is old enough today to have watched movies in a way we no longer do, should write this book. Could someone who grew up in our hyper-technological world, who hasn’t had to “suffer” to watch a film, write something as insightful? These days it’s so easy to watch a movie; we can buy or rent a DVD, or even better, stream it online. Back then, you had to make the effort to go to the movies, since home video only advanced in the 1980s. Just as with music, if you really liked a band you would have to go and watch them at a concert, keep your ears peeled for their song to come on the radio. These days, consuming culture is no longer an act of sacrifice. Your boast that you found Arcade Fire first before they became big would sound hollow, since now you can go on Youtube and immediately hear a song, and decide just as quickly whether you like them.

Still, Dyer keeps to old habits. Even today he forces himself to watch Stalker only in cinemas or at festival screenings so that it will forever retain its specialness, each viewing of the film different according to where he watches it. Some would call him a film snob because he insists “great cinema must be projected”, not merely seen on television, and offers up the idea of “cinematic pilgrimages”, where people would go to a small cinema screening only one film for the entire year, to pay respects to the cinema greats of the past. It’s a beautiful, if quaint idea—and not out of place in this increasingly brave new world where we often yearn for the old, the vintage, holding Prohibition-themed parties and the like.

What really changes our way of appreciating and consuming culture, however, is the concept of time, which has changed over the decades. On one end there’s “Tarkovsky-time”, and on the other “moron-time”, ticking on heedlessly in the 21st century where “no one can concentrate on anything longer than about two seconds”. Zona is an antidote to today’s heedless consuming of culture and our immediate retweeting and “liking” of everything on Facebook, which is all that is asked of us; there is no longer any need to be able to articulate why you like something or why it has such a hold on you, to put into words something we feel but cannot say. This is precisely why we should be grateful for writers like Dyer, and books like this.

In a droll admission, Dyer likens himself to Writer, who wants to go to the Zone to find inspiration:

Man, I know how he feels. I could do with a piece of that action myself. I mean, do you think I would be spending my time summarising the action of a film almost devoid of action—not frame by frame, perhaps, but certainly take by take—if I was capable of writing about anything else?

Of course, this is merely a conceit. What he means to say is that he “summarises” Zona because he can. Dyer has written across several genres, often blurring the lines between them. He can write about anything, or nothing. In fact, he can turn what is for other authors a non-subject into a subject. His book Out of Sheer Rage, which was supposed to be an academic study of the English novelist D. H. Lawrence, turned out to become a memoir of his failed attempt to write a study about Lawrence. You’d think that writers who write like Dyer would invite criticism for being too self-indulgent, and though I think this may sometimes apply to sections of Zona, as a whole that cannot be said to be true of the book, nor of Dyer. Admirably, he has made himself an exception to many rules.

There are a lot of cultural references to swallow in Zona, and I found many of them alienating, simply because I am not as well read or as exposed to films, and because some of them happened before my time. Luckily, most of them are contained in the footnotes, some of which run several pages long; and in any case, Zona is not a book you read once and get over with. It contains many ideas, and in time I imagine I will visit some of those quasi-extraneous things Dyer mentions and come back again to their passages, and perhaps I will start to care about them as I’ve come to care about Stalker. Every time you come back to Zona you will see it anew as your experiences continue to shape you, but it also works the other way: Zona reminds us that good culture—books, movies, music, etc.—have the ability to shape the way we see the world that comes after it, each in a tiny, often imperceptible way.

Published 2 Feb 2012. Available in hardback and ebook. Thanks to Canongate for providing a review copy.

If you’ve never read Geoff Dyer’s work and would like to have a taster, please download this app; Canongate has said that the app will be continuously updated with new content as they become available.

Geoff Dyer joined us recently at Litro Live! on 14 July at the Serpentine Pavilion in Hyde Park to celebrate the launch of Litro #117: America.

About Emily Ding

Emily joined Litro in April 2012 as Literary Editor & Web Designer. She made over the website and introduced new developmental and editorial features to strengthen Litro's online presence. She left her position in January 2013, taking a backseat as Contributing Editor to concentrate on writing. She is a freelance journalist with a special interest in travel writing and foreign reporting (with an inclination for Asia and Latin America), and is now based in Malaysia. English is her native language, but she also speaks Mandarin and Spanish, having spent 2007-08 travelling in Central America.