You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingMoney and sport go together. In the last few weeks, as the credibility of cricket wobbled under allegations of corruption and match-fixing , I’ve been reading the funny and satirically scathing baseball stories of Ring Lardner, whose naive ball-players, obsessed with cash and celebrity, sound strangely familiar.

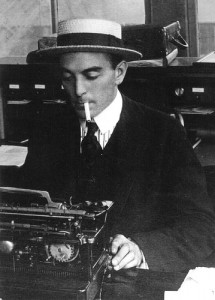

Regarding himself as a sports journalist first and a fiction writer second, Lardner started writing stories about baseball to fill newspaper column inches in the early 20th Century. He was off-hand about the critical acclaim his work received from peers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, or Dorothy Parker, who described the ‘strange and bitter pity’ of his stories. He was a modest writer, who saw himself as a hack rather than a literary genius. When his stories were first collected together as a book, Lardner had to write to the magazines who had published them to ask for copies, as he hadn’t bothered keeping any himself. When he died in 1933 at the age of 48, he had a memorable but tiny body of literature to his name.

Lardner’s best-known work, You Know Me Al, is a series of letters written by the fictional Jack Keefe, a bush-league ball-player who’s just made it up to the ‘big show’, the major leagues. Jack writes home to his old friend Al, reporting back on the contracts he gets, the games he plays and the people he meets: pitchers, strikers, left-handers, coaches, managers and hangers-on.

Lardner was brilliant at recording the American vernacular as it was really spoken. Before Lardner, cod-American speech had been used by writers like Mark Twain or Harriet Beecher Stowe, who tried to write speech as they imagined their characters spoke it, but their ‘La sakes’ and ‘looky yonders’ sound twee today. Lardner on the other hand, had the knack of writing American as someone like Jack Keefe truly spoke it. You Know Me Al, written with Keefe’s terrible spelling, dodgy grammar and sports slang, holds your attention even if you don’t know the first thing about baseball. This is Keefe telling Al about a recent game.

‘Well I come up in the eighth with two out and the score still nothing and nothing. I had whiffed the second time as well as the first but it was account of Evans missing one on me. The eighth started with Shanks muffing a fly ball off of Bodie […] Callahan says Go up and try to meet one Jack. It might as well be you as anybody else. But your old pal didn’t whiff this time Al. He gets two strikes on me with fast ones and then I passed up two bad ones. I took my healthy at the next one and slapped it over first base. […] I felt so good after the game that I drunk one of them pink cocktails. I don’t know what their name is.’

Keefe writes (and spells) as he speaks, and the words leap off the page in his slow but insistent voice. It’s subtle, funny and engaging, and Lardner’s ear for spoken language is perfect. The journalist H. L. Mencken wrote that he’d once used the word feller in a conversation with Lardner, who asked him “where and when … did you ever hear anyone say feller?” Mencken realised Lardner was right. No matter what literary types might put between their speech marks, the ordinary American pronounced the word fella.

Over the course of You Know Me Al, Lardner’s Jack Keefe emerges as a childish, naive, stingy and semi-literate buffoon, conceited, not half as talented as he believes, blind to his own faults and unaware that he’s the butt of his teammates’ jokes.

But despite all this, you can’t help rather rooting for Jack Keefe, caught up in a world far more sophisticated than he is; a world obsessed with winning, peopled by players chasing paycheques and women out to take the gullible star of the moment for all he’s got.

It’s a world where money corrupts the knowing and the innocent alike. Jack Keefe is obsessed with how much he’s worth, and how much he’s paid. As he gets embroiled with drinking, gambling and girls, Keefe goes from resentment over spending fifty cents on a meal to worries about keeping his new wife happy with ‘mohogenny’ furniture for their flat. In nearly every letter he agonizes over his finances, begging never-to-be-repaid loans from his friend Al or setting out the costs of his wedding, down to the flowers and candy at 50 and 30 cents respectively.

Ring Lardner’s Keefe is as relevant a character now as he ever was – substitute football for baseball and Wayne Rooney for Jack Keefe and You Know Me Al is a very modern set of stories. Sport has always been populated by men who have the brawn and talent but maybe less of the brains or self-awareness, who are suddenly exposed to adulation and more money than they’ve seen in their lives before, and the effects can be devastating. 18 year old cricketer Mohammed Amir’s glittering career, ruined through naivety, George Best or Gazza, brittle and delicate shadows of themselves – in the big show, sport raises its champions high and brings them down hard.

Larder was no stranger to the sports scandal. As a sports reporter and close associate of the Chicago White Sox baseball team, Larder was devastated when it emerged in 1919 that members of the team had taken bribes from gangsters to throw matches and lose the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds, in what became known as the Black Sox scandal. It shook Lardner’s faith in his friends and associates, and in sport itself.

The American judge Earl Warren once said “I always turn to the sports pages first, which records people’s accomplishments. The front page has nothing but man’s failures.” Ring Lardner would surely have disagreed: his fiction reveals that the sports pages are as full of human failure as any other part of the paper.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.