You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingShould song lyrics ever be called poems? Clémence Sebag explores the murky world of musicians who claim poet status.

What do Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, Jarvis Cocker, Ian Dury and Paul Simon and Paul Muldoon have in common? These singers have all had lyrics published in collections which essentially present themselves as poetry.

If, like me, you were one of 15,000 or so shouting “Leonard! Leonard!” or “I’m your woman” at the London leg of Leonard Cohen’s Old Ideas tour in earlier this month, you might already know why these singers transition from poetry to lyrics or vice versa. If not, you might be in the camp of those who are furious that The Independent has put a Canadian songster on the same pedestal as an English romantic poet: “If an alien race wanted to understand human obsession, the pungent words of Keats and Cohen (“Many loved before us/ I know that we are not new”) would probably be the best place to start.”

Here I should point out that Cohen is a poet is his own right. But what about the others? These “lyrical collections” are evidence of the increasing converging of poetry and lyrics, with lyricists sometimes taking a leaf from poetry for lyrical inspiration. But while with developments like spoken word and sound poetry, poetry is oral and musical; “poetic” lyrics are growing silent – with singers wanting to add “poet” to their curriculum vitae switching the music right off from their songs.

“Sort of like poems”

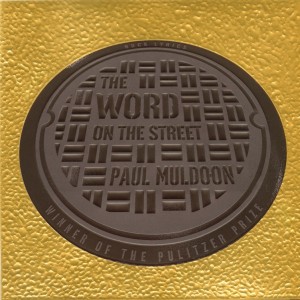

Irish poet and musician Paul Muldoon is the latest to join the “lyrical collection” ranks with The Word on the Street, published by leading poetry imprint Faber in February this year (there’s also “music inspired by these lyrics” – not the other way around).

Muldoon told The Guardian: “these things are not quite poems, and yet they are sort of like poems.” This is precisely the imprecise position of publishers of collections of lyrics – how otherwise could you justify publishing lyrics stripped of music? If you were convinced they could not stand up against the thundering silence it would simply be a cynical money-making enterprise. The Word on the Street isn’t Muldoon’s first collection of lyrics either; there was General Admission in 2006 and last year’s Songs and Sonnets, in which, as the name suggests, Muldoon looked at the links between verse and song. Muldoon in The Guardian again: “At school we studied […] Gaelic poetry, which we were often taught as songs. Yeats wrote a fantastic number of poems with the word song in the title, and used, as I myself have been using, the refrain.” Evoking the blur between the two, Muldoon says: “I think I’ll be back to poetry next, but I can’t help thinking that I might just continue to do both.”

Dylan’s a poet and he knows it

But when it comes to blurring the lines between poetry and lyrics, Bob Dylan (who stage-named himself after Welsh poet Dylan Thomas) remains the most talked about example, by scholars and writers alike – to the confusion of some and fury of others who see the publication of Dylan’s collected Lyrics 1962-2011 as immensely cynical.

But when it comes to blurring the lines between poetry and lyrics, Bob Dylan (who stage-named himself after Welsh poet Dylan Thomas) remains the most talked about example, by scholars and writers alike – to the confusion of some and fury of others who see the publication of Dylan’s collected Lyrics 1962-2011 as immensely cynical.

Much is made of the fact that Dylan has been tipped as a Nobel Prize winner every year since 1996. Yet with only one memoir and one prose and poetry collection (Tarantula, 1971) – which received a rather mixed reception – to his name, it’s a fair bet that those putting money on him as a literary man are counting his collected lyrics as part of his literary oeuvre. Poet Allen Ginsburg wouldn’t disagree. According to Ginsberg, in Dylan’s 1975 Idiot Wind (“Idiot wind, blowing like a circle around my skull, / From the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol”), the metaphorical relation between the head and the head of state, both of them domes, and the “idiot wind” blowing out of Washington from the mouths of politicians, make it the “great disillusioned national rhyme”.

This is from Dylan’s album notes to The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan back in 1963: “Anything I can sing, I call a song. Anything I can’t sing, I call a poem.” Then again, the lyrics vs. poetry picture is clearly a blurry one for Dylan who once claimed his favourite poet was (singer) Smokey Robinson, only to later change his answer to French poet Rimbaud. There’s definitely Another Side of Bob Dylan and he flags it up in his 1964 album title as well as on the track I Shall Be Free No. 10, with a jesting reference to the eternal debate: “Yippee! I’m a poet, and I know it / Hope I don’t blow it”.

Dylan himself tired of the debate and, in 1965, broke the spell of ambiguity, telling journalists: “I think of myself more as a song-and-dance man.”

Black and white vision

As God and/or Dylan suggests, (Dylan: “Man gave names to all the animals / In the beginning”), the first step to taking ownership of something is naming it, in other words defining it. The Oxford and Cambridge dictionaries agree that a poet is “a person who writes poems”, suggesting that the mere act of defining oneself as a poet suffices to make one a poet. Patti Smith fits this bill: her first love, long before the seminal Because The Night, was poetry. When she started out in music, she described herself as a poet, who happened to be performing poetry to music.

Don’t tell that to poet, critic and poetry professor Glyn Maxwell (On Poetry) who would happily build a wall to keep the musicians out – with Bob Dylan topping his hit list. There’s a place for poets and there’s a place for musicians, he says, and they shouldn’t play together: “Bob Dylan and John Keats are at different work. It would be nice never to be asked about this again.” For Maxwell, it’s all pretty, well, black and white: “Poets work with two materials, one’s black, one’s white”. “You want to hear the whiteness eating? Write out the lyrics of a song you love … If you strip the music off it, it dies in the whiteness, can’t breathe there.” Writing about Paul McCartney’s 2001 effort Blackbird Singing: Poems and Lyrics 1965-1999 (published by poetry imprint Faber), John Kinsella somewhat less poetically Observe[s]: “Reading the song lyrics, you can’t help singing them in your head, which detracts from the poetic experience in some way, where the language generates its own music”.

Don’t tell that to poet, critic and poetry professor Glyn Maxwell (On Poetry) who would happily build a wall to keep the musicians out – with Bob Dylan topping his hit list. There’s a place for poets and there’s a place for musicians, he says, and they shouldn’t play together: “Bob Dylan and John Keats are at different work. It would be nice never to be asked about this again.” For Maxwell, it’s all pretty, well, black and white: “Poets work with two materials, one’s black, one’s white”. “You want to hear the whiteness eating? Write out the lyrics of a song you love … If you strip the music off it, it dies in the whiteness, can’t breathe there.” Writing about Paul McCartney’s 2001 effort Blackbird Singing: Poems and Lyrics 1965-1999 (published by poetry imprint Faber), John Kinsella somewhat less poetically Observe[s]: “Reading the song lyrics, you can’t help singing them in your head, which detracts from the poetic experience in some way, where the language generates its own music”.

In fact, Maxwell and Kinsella are in good company, although it might not be the company they expected; there are musicians who complain about the mix-up too. Paul Simon doesn’t take kindly to being called a poet: “The lyrics of pop songs are so banal that if you show a spark of intelligence they call you a poet. And if you say you’re not a poet then people think you’re putting yourself down. But the people who call you a poet are people who never read poetry. Like poetry was something defined by Bob Dylan. They never read, say, Wallace Stevens.”

Is it for lack of good (and accessible) poetry that we turn to lyrics and call them poems? In a poem from his collection Hay (1998), the poet (and rock band lyricist) Paul Muldoon seems to agree, writing of Leonard Cohen; “his songs have meant far more to me / than most of the so-called poems I’ve read”.

Renaissance man

While Muldoon merely compares Leonard Cohen‘s lyrics to poetry, the reference is telling. Cohen started out writing poetry (the serious sort, the sort that was never set to music), and indeed never abandoned literature, writing poetry and lyrics as separate entities, as well as adapting five of his own poems into song lyrics (e.g. Suzanne). In fact, The Independent, reviewing Cohen’s 2012-2013 tour, refers to him as “The Canadian poet”, while The Telegraph paraphrases poet Dylan Thomas’ famous villanelle (perhaps in reference to Cohen’s own musical Villanelle For Our Time) to describe Cohen: “Nobody is raging against the dying of the light more spectacularly than Leonard Cohen.”

For Cohen the two arts feed off each other: the name of his album, Death of a Ladies’ Man (1978) is also the title of one of his poetry collections.

Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (1993) is a venture illustrating Cohen’s un-partitioned vision of art, containing over two hundred poems, several novel excerpts, and close to sixty song lyrics.

Poetry.org notes that “his fans continue to embrace him as a Renaissance man who straddles the elusive artistic borderlines. After nine books of poetry and more than 15 music releases, Cohen seamlessly re-institutes that ancient notion of the lyric as belonging to both verse and song.” The Independent seems to agree, with its headline: Leonard Cohen – The 78-year-old troubadour enjoys a mournful waltz. Because what is a troubadour? One of two things: “a French medieval lyric poet composing and singing in Provençal in the 11th to 13th centuries, especially on the theme of courtly love” or “a poet who writes verse to music”. Cohen is Canadian, not French, so it must be the former.

Openly following in Cohen’s footsteps, Paul Muldoon exemplifies the artist for whom a single label simply will not do. He has a Pulitzer Prize for poetry and is a T. S. Eliot Prize winner, former Oxford Professor of Poetry, and poetry editor at The New Yorker, but also the lyricist for several bands (currently the Wayside Shrines). He was described in the New York Times as “a shape-shifting Proteus to readers who try to pin him down”. It is telling that those selling his latest effort, The Word on the Street, just like those reporting on it, cannot seem to decide how to describe it, referring to it alternatively as printed rock lyrics and as a poetry collection. Describing the product, Amazon writes: “A vibrant new collection of poems—that also double as rock songs—from the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet. In his new book of rock lyrics, Paul Muldoon goes back to the essential meaning of the term “lyric”—a short poem sung to the accompaniment of a musical instrument. These words are written for music most assuredly, with half an ear to Yeats’ ballad-singing porter drinkers and half to Cole Porter”.

Openly following in Cohen’s footsteps, Paul Muldoon exemplifies the artist for whom a single label simply will not do. He has a Pulitzer Prize for poetry and is a T. S. Eliot Prize winner, former Oxford Professor of Poetry, and poetry editor at The New Yorker, but also the lyricist for several bands (currently the Wayside Shrines). He was described in the New York Times as “a shape-shifting Proteus to readers who try to pin him down”. It is telling that those selling his latest effort, The Word on the Street, just like those reporting on it, cannot seem to decide how to describe it, referring to it alternatively as printed rock lyrics and as a poetry collection. Describing the product, Amazon writes: “A vibrant new collection of poems—that also double as rock songs—from the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet. In his new book of rock lyrics, Paul Muldoon goes back to the essential meaning of the term “lyric”—a short poem sung to the accompaniment of a musical instrument. These words are written for music most assuredly, with half an ear to Yeats’ ballad-singing porter drinkers and half to Cole Porter”.

Meanwhile, the marketing of the thing itself sends mixed messages: as the Irish Times reports: “Unpunctuated, right-justified and printed in a bold and blocky font, the lyrics look like more like a CD insert than a book of poems.” However, for the cover image “what looks initially like a single in its sleeve [the dimensions essentially match that of a CD] is in fact an embossed manhole cover that bears the book’s title and is set against a gold-flecked road surface – literally, the word on the street”.

What does Muldoon have to say about his “product”? Even he isn’t too sure: “The tradition of reading lyrics on a page is a little bit iffy. Some of us of a certain age will remember lyrics on album sleeves … One took them somewhat seriously, but maybe not completely seriously. I’m a bit conflicted myself.”

What’s in a name?

If composer and lyricist are not one and the same, the lyrics of a song are likely to have been created separately from the tune. If the lyricist once thought the lyrics looked good naked, it isn’t such a stretch to think they might look good un-dressed again. So the fact that some lyrics share many traits with what is considered poetry in the stricter sense may have something to do with the birthing process. Other lyrics die a horrible death without their other half, and I have to agree with Maxwell that it’s an ugly divorce when you separate Beatles’ lyrics from their spouse (think: “love me love me dooo”).

So can lyrics be considered poetry? Muldoon talked to the Guardian about “popular stuff that lived in a sort of netherworld between poetry and song” and dedicated The Word on the Street to Paul Simon (singer) and Leonard Cohen (poet and singer) just to keep us guessing. Essentially, the answer to that question is high up on a fence. God (and Maxwell) may be bent up on naming things, but at the end of the (sixth) day, in the words of the bard of Avon himself: “That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.”

Cohen’s creativity is cleared fuelled by fluidity between genres, and, at the later stage of reception of his art, this same fluidity has certainly played a part in his early poetry reaching a wider audience. In my case, it was love of Cohen’s songs that led me to discover his poetry. And if any one of the remaining 14,999 people at the O2 on Sunday were still in the dark about Cohen’s poetry credentials, he made sure to correct that by putting several of his poems on the three-hour set list. Call it poetry, call it reading poetry, call it spoken word, call it what you will, but 79-year-old multi-talented Cohen can certainly draw a crowd. Rules and walls were made to be broken. So perhaps where Maxwell is missing the point is how much the blurring of poetry and lyrics can do for each of them. Black and white are not colours. Grey is.

Read the first part of this series on the relationship between music and poetry here.

About Clémence Sebag

Clémence Sebag is roamer, she started out as a West Londoner, worked her way up North, then ventured down South until all that was left was East. She tried Rio and Buenos Aires but couldn't get used to the weather. By day she works as a literary translator, by night she writes book reports for a literary scout. She wants to be a writer when she grows up and everybody knows Paris is where writers live. Fall-back career: literary groupie. She Blames Bridget Jones for not having gotten around to penning the 10th draft of her 31st novel. Meanwhile, you can find some flash fiction from her Goldsmiths Creative Writing MA here. She also dabbles in poetry and you can find her in the anthology The Dance Is New. Best place to find her: Café de Flore. If Paris is too far, Tweet her @clefranglaise or follow her blog.

Paul McCartney calls his “poems,” “naked poems” (supposedly without music); Paul Simon (in his song lyrics) refers to himself as a “poet.” What are lyricists, other than poets to music (refer to other poets and their comments on songs/music) being the cummulation of the best of both?