You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingI was interested to read today that Marvel Entertainment has decided to kill Spiderman. Although Columbia Pictures have rebooted the Spiderman film franchise, with The Amazing Spiderman set to be released in July 2012, in Marvel’s Ultimate universe it seems that Peter Parker’s days are numbered.

Writers are the controllers of their own fictional universe, with the power to sculpt and structure every facet of the inhabitants’ lives, but despite this god-like power, many writers are reluctant to lay waste to their literary creations. Killing a major superhero is a bold move and it is by no means an easy one; indeed, Brian Bendis openly admits to composing the story “with tears in my eyes like a big baby”. Spiderman’s death makes me wonder: should authors avoid the deaths of their heroes and heroines at all costs?

Certainly, it’s less of a problem knocking off a few minor and irrelevant characters, but killing a major protagonist is a risk and can have some serious consequences for a writer and their work. It is not a decision to take lightly. After chronicling every nuance of feeling and obscure physical attributes of our creations, one becomes emotionally attached. It’s not uncommon for an author to “fall in love” with a character they’ve created, going as far as to change the entire story just to spare their hero a grisly and unpleasant end.

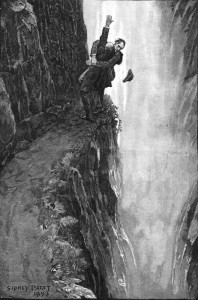

Of course, there are some authors who have little or no attachment to their characters at all and cannot wait to be rid of them, plotting the demise of their central figures with a sort of homicidal glee. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, for example, found eventually that he had very little time for Sherlock Holmes, accusing his most famous creation of taking “his mind from better things” and complaining to his mother that he was weary of the detective. And so, there was no other way around it: Holmes must die and, in December 1893, Conan Doyle published The Adventure of the Final Problem in Strand Magazine, in which Holmes and his nemesis Moriarty plunge to their death from the Reichenbach Falls. Conan Doyle may have thought he had seen the last of the world’s only private consulting detective but what he hadn’t anticipated was the uproar following the death of Holmes. Over 20,000 people cancelled their subscription to Strand Magazine and Conan Doyle faced an onslaught of appeals to bring Sherlock back to life. It was only after eight years that he conceded a little, writing The Hound of the Baskervilles but making clear at the same time that it is a posthumous tale, set in the years before Holmes’ death. Such was the immense pressure from readers and publishers, however, that Conan Doyle had to resurrect Sherlock Holmes from the dead in The Empty House.

As Conan Doyle found out the hard way, killing off a main character can seriously anger and alienate your readership. Many a novel has been discarded in sheer frustration after the discovery of a beloved character’s death, with some readers giving up entirely on their favourite authors or series in protest. As a reader, you invest yourself emotionally in a character and, whilst watching their lives unfold, you grow to care about their wellbeing. To have all that snatched away is cruel and readers often find it hard to forgive an author who has effectively wasted their time and “betrayed” them.

Killing a character, however, is sometimes a fundamental part of the story and, when handled properly, can have the potential to elevate a tale from being merely pleasant to read to becoming moving and memorable. So just how can one kill a main character without arousing the hatred of the reading public? Below are a few tips and tricks I’ve garnered from the resources of the world wide web in order to make the murder of your heroes and heroines as smooth as possible.

- Make the Death Matter. If the protagonist dies in a futile and obscure accident with little relevance to the plot, it can make one question the point of the entire story in the first place. Major character death should never be treated as an irrelevant afterthought. If, however, the hero dies for a greater good—whether to save a loved one or repent for irreconcilable evils—readers can respect and even admire the decision to give up a life for something more important.

- Keep A Balance. Don’t go overboard and massacre everyone (unless you’re writing a dark and twisted horror story!) Also, if you are dealing with multiple character deaths, try to keep a balance of how everyone dies. Don’t have every death as a dramatic, emotional climax with an angst-ridden soliloquy at the end, or the reader will quickly become bored.

- Foreshadow a Death. In the prologue of “Romeo and Juliet”, we are warned that the protagonists are “star-crossed lovers”, cursed and doomed from the very beginning and, throughout the play, hints are dropped to remind us that “violent delights have violent ends”. Although you want to surprise your reader, leave subtle warnings that a death is on the cards so that after the shock, the reader can go back, find the clues, and it will all make sense. Furthermore, sometimes knowing which way a story is heading, and being able to prepare for the death of a main character, will heighten the suspense and intensity of emotion when the final moment eventually arrives.

Killing a major character is by no means a requirement of great literary fiction. If you are writing a light-hearted tale or a children’s novel, I would advise against traumatising any unsuspecting reader and killing for the sake of it. Mostly, readers like happy endings but we are not totally naïve; we know that the world we live in is not all hearts and flowers and, sometimes, our favourite fictional heroes must die. It can be a good idea, however, to add an affirming note after the death. If we are to accept a death, it can be a comfort to many readers to know that there is a silver lining behind the dark cloud. In my opinion, when thought out properly and written for the right reasons, a character’s death can affect and resonate with a reader a hundred times more than a perfect, happy ending could.