You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

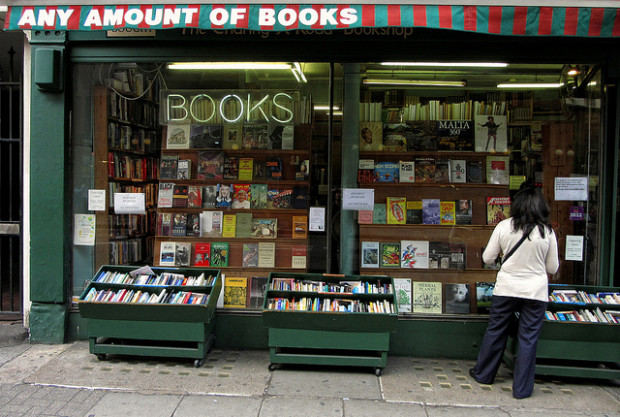

“Looking for something in particular?” The shopkeeper peers over his glasses.

“Just browsing, thanks.”

He clears his throat. Or was it a murmur? No matter, there is a world of old books – some rare, some as common as pigeons – to negotiate. I am in a second-hand bookshop and my life for the next hour or two will be a kind of dusty daydream. Yes, I am looking for something in particular but I’m not sure what it is. I’ll know it when I see it.

Exploring the musty alcoves of a second-hand bookshop, out of the fresh air, away from the glare and grimace of the world, its crass vicissitudes, has something of an illicit flavour. I imagine this is how a young wizard of the baize must feel when bunking off school to hone his craft under the sickly lights of a snooker hall. The dedicated bibliophile seeks out dim-lit dens filled with the old and the rare, the forgotten and the cherished; we feed on the unread, the unsold, the unfashionable and the unwanted.

From the locked cabinets of Cecil Court in London (where first editions flaunt themselves in designer jackets) to the hurly-burly of the Manchester Bookbuyers stall on Church Street (Seek and Ye Shall Find, urges a scrawled sign above the jumble of 50p bargains), the second-hand bookshop is more than a storeroom of yellowing paper and mouldy calfskin, it is a space permeated with memory, loss and yearning. Here, among all these books, one feels the accumulation of silent hours, of thoughts, dreams and private smiles; we are surrounded by spirits of the readers who once possessed (and loved or despised) the contents of the shelves we so keenly inspect. Listen carefully, and you will hear the tick of the clock in the gloomy school library from which Susan Pigott of 4B borrowed Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1954; listen again and you will hear the beating of her heart as Hyde goes on the rampage. And that’s the creak of the leather armchair in which PL Marshall read GK Chesterton’s The Victorian Age in Literature (Williams & Norgate, 1925), a decent edition with deckle edges and sun-faded spine. The handwritten inscription on the front free endpaper reads: PL Marshall May 1968 Woodham Mortimer. I used to think that Woodham Mortimer was a stout but tweedy gent with a plush moustache, Marshall’s friend or colleague perhaps, but it’s actually a village in Essex.

There are stories in bookshops, and not all of them between covers. Writers are readers. With a nose full of dust and sneezes, we inspect the shelves, following the procession of names – Hanley, Hardy, Harrison – hunting for that singular gem, the elusive edition, and feeling deflated when it does not appear.

All readers dream of the perfect bookshop, a lair full of curious volumes (at curiously reasonable prices): uncommon beauties; obscure and frightening treatises on the occult; novels with dapper jackets by Mozley, Rowland or Woodcock; obsolete medical guides with bizarre illustrations; snazzy bright American paperbacks from the 1960s. Now there is the internet – the global dream or nightmare of endless commerce. You can buy any book you desire, provided you have enough money or credit. Click: the Collected Works of JM Synge in four smart volumes (Oxford University Press). Click: William Sansom’s Among the Dahlias whose protagonists according to the flyleaf “are involved in strange encounters and wryly comic predicaments”. (My copy smells of burning.) I love the speed of buying books online, skimming through a writer’s entire output, but I remain loyal to the bookshop, to the unexpected delights of the shelf.

On entering a favourite and frequently visited second-hand bookshop, your eye picks out the new acquisitions almost immediately, vivid against the tired, uninspiring spines. Some books refuse to be bought, by you or anyone else; they are always there, the great unsold, as permanent a fixture in the shop as the creaking floorboard in the photography section.

In my early twenties I was stalked by the hardback edition of Kingsley Amis’s The Riverside Villas Murders. It had an attractive greenish spine on which the author’s name appeared in three sections, KING, SLEY and AMIS, its jazzy blue lettering easily readable from a distance. It turned up in every bookshop I visited, sometimes in pairs or triplets, and it never failed to attract my attention. Even to this day it still jumps out at me from a shelf. I’ve never bought it, never read it. Perhaps I should, to break the curse. Perhaps the truth I’ve been searching for is in that book.

Behind the till, almost in camouflage, lurks a character that might be made of glue and dust. There’s the intoxicating smell of old paper and dry bindings, a civilised fug, as aromatic to the reader as hops to a toper. And always there is a sense of discovery, anticipation, even in the most familiar den.

Visiting a bookshop for the first time, one feels obliged, in a pleasant way, to inspect every shelf, especially those dusty alcoves packed with books on topics one generally overlooks. That’s part of the fun of the second-hand bookshop: finding unexpected treasure. (It is also a drawback – you can’t guarantee to find what you’re looking for. That’s why it’s best not to look for anything in particular, but to browse with an open heart, as if daydreaming.) In some gloomy recess at the back of the shop, you may find the handsome Andre Deutsch edition of Alfred Metraux’s Voodoo in Haiti or Folktales of Lancashire by Frederick Grice (with 28 line drawings and a pictorial map by NJP Turnbull). In the labyrinthine wonder of the excellent Carnforth Bookshop, I found Word for Word, An Encyclopaedia of Beer, published by the brewery Whitbread & Co Ltd, with an introduction by Ivor Brown, one-time editor of The Observer and confirmed enemy of modernist poetry: “It has now been discovered that half-baked intellectuals will worship baby-talk and even persuade other people to pay for it” (I Commit to the Flames, 1934). Word for Word was published in 1953 to give the general reader “a picture of one of Britain’s oldest industries”, a literary version of the infomercial. Not only did this slim volume introduce me to such mysterious words as dadloms, gyngleboy, bouge, trouncer (all writers enjoy the jargon of trades and hobbies) but it led me to discover Derrick Harris, the book’s illustrator. A brilliant wood engraver, Harris’ art is robust and joyful, full of bold patterns and gentle wit. My favourite illustration in the book shows the exterior of a pub called The Crown. I do not know if the pub is real or imagined, or a combination of both. It looks small and cosy, with a church-like door and frosted windows – the sort of place that lights up the thirsty soul.

A second-hand bookshop – especially a bookshop we have not visited before – tempts us into unknown territories. Philosophy, religion, the occult, local history, psychiatry, sculpture, transport. (Transport is particularly good for the fanatical specialism of its titles). There’s very little I will ignore, apart from a shelf of books on Arsenal. Local history is a good source of oddities, and should a writer be lost for inspiration there are plenty of ideas in even the most unprepossessing volume of provincial folklore. (I believe Shakespeare employed a similar technique.)

Second-hand bookshops, like pubs and art galleries, are excellent places for collecting strange characters and odd conversations. I’ve certainly heard some daft things. “Oh, I love Dickens but only on telly”and “Have you got the latest Jane Austen?” In Drif’s Guide to the Second-hand and Antiquarian Bookshops of the British Isles, six editions of which were published in the 1980s and 90s, both customers and booksellers were shown no mercy. Here are some of Drif’s pithy descriptions: “Primarily prints and bindings. Red braces welcome.” “Extremely esoteric, and that’s just the customers.” “Small, keen on comics and romantic poetry. Almost a description of the owner.” Drif devised his own abbreviations and terminology. “FARTS: Follows you around recommending the stock.” A Samuel Beckett Special is ‘a second-hand bookshop where it is not always possible to tell what is going on, the windows often have just two or three drearily strange books in them’.

The other day I was looking at what was on offer at the occasional bookstall on Oxford Road in Manchester (opposite Abdul’s splendid kebab shop). A chubby man edged towards me, selected a book at random and showed it to me. “Look,” he said, “this is the book for you.” The book was How to Write a Successful Business Plan. He laughed. “It is just my humour,” he said, as if to reassure me, “it’s just my humour”. But I was not offended, merely confused. And perhaps a little frightened. He went away and tried his humour on a pale young woman, pulling out another book, Leatherwork Techniques. She certainly looked concerned.

The anticipatory thrill of entering a bookshop is similar to the buzz I used to get on visiting a pub. Every pub offers familiarity and comfort: the cheery warmth captured in Derrick Harris’s engraving. You know the routine, you know the faces, you certainly know there’s a hangover coming. Yet there is still a sense of excitement, of starting from scratch – where will the booze take you this time, to the gutter or the casino, what will you say or do? A bookshop has a similar if less toxic magic. Once inside the shop there is that rush, a lightheaded moment of acclimatisation as your senses take it all in. Where to start?

Slackly organised shelves are the bookworm’s enemy. The occasional alphabetical mishap is acceptable – finding a Graham Greene before an Alasdair Gray acts as a teaser to the bibliophile, encouraging attentiveness and warning against complacency. But if the shop is too messy then the bookworm becomes demoralised. The hunt becomes a game of chance, a crude lucky-dip. Frustration and fatigue set in. A shop I found by chance in North Wales was so cluttered with stalagmites of books that it was perilous to negotiate. There were piles and heaps of glossy hardbacks, toppling boxes of Penguins and Bantams, tables groaning with pamphlets, paperbacks, dictionaries, big glossy sporting biographies. The shelves were equally disordered. A run of novels would suddenly give way to a history of Shropshire or Wogan on Wogan and then veer off into gardening and back to novels again. Investigating a stack of 1960s hardbacks, I stooped to lever one out (steady now), turned it over, and the shopkeeper, who I hadn’t noticed before, barked: “No, not them! They’re not for sale. I’ve not done them yet.” By “not done” them yet’ I presumed she meant she hadn’t made a note of them in her tatty pad. Perhaps feeling guilty, she parted the curtains of her hair, and tried to explain herself. “I need to sort all this.” She waved at the room as if it were a bus to be stopped. “I’m in the middle of… I’m organising it, you see. I don’t want things to fall over. You might hurt yourself.” A bespectacled man in a grey anorak entered the shop and enquired about a book in the window. He tried to bargain her down from twelve to ten pounds. She refused and the man left empty-handed. She was mean as well as disorganised. I decided not to buy anything. A history of surgery had looked promising but its contents were tamely academic. There might have been treasures in that shop but the terrain was too rough for me. As I left I wished her good luck, but she didn’t hear, she was crossing something out in her jotter.

Bookshops are pubs for the mind. Pubs and bookshops: I look for these first when I’m in a strange town. Pubs are less important to me now but their sad beauty remains. Pubs and second-hand bookshops: both are disappearing from our towns and suburbs. When rumours of the internet began to reach me in the 1990s, I delighted in being a Luddite. I was still getting to grips with the magic of compact discs. My attitude was phony and did not last long. A friend mentioned that he had read Nabokov’s excellent book on Gogol. I had been hunting for that book for years. “Where did you get it?” I asked. “Online,” he said. I felt cheated. I had put in the hours, searching and asking, but he had won it with a click and a card.

I grew up in a household mostly without books. Mum had her nursing manuals and Catholic missals. Dad had his A-Zs. Those alone could keep me occupied for hours. I pored over the London A-Z with religious intensity. The medical books filled me with delight and horror. The catechisms were less enticing, although they contained some gaudy pictures of tortured saints. Books served a function and were kept hidden in cupboards, along with blankets, bandages and dad’s cans of beer. There were no bookshelves. I went to the library every week and borrowed books about football, the Second World War, ghosts, flags, trains. Very rarely did I dabble in the soft fancies of fiction. I was about fourteen when I read Animal Farm in one sitting on a Saturday afternoon. I was incredibly moved by the death of Boxer. Later, there were books I had to read for school, such as The Go-Between (I like Hartley better now than I did then) and Twelfth Night (I was Malvolio when we read it aloud in class, delivering his final line I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you with grim gusto). These books were supplied by school. But at “A” level you had to buy your own textbooks.

So as a boy I didn’t have much to do with bookshops of any kind, although I loved the local library and my uncle’s odd collection of paperbacks (atomic warfare, UFOs, the Bermuda Triangle, ancient astronauts). The only bookshops that I remember being in Ilford during my childhood were WH Smith (a bright heaven on two floors, where I bought Grange Hill Stories with some tokens I had won) and a murky, sinister place on the fringe of the town called Edward Terry Books.

The name intrigued me, emblazoned in white letters against a red background. The windows were covered in yellow film and the door opened into what looked like perpetual darkness. It was at the end of a row of rather uninteresting shops, across the way from a supermarket where I would later take a Saturday job. Small and shabby, making no concession to commercial allure, Edward Terry’s den looked intimidating, even seedy, and was therefore attractive to a nervous youth. For a while I supposed must be some kind of adult shop, selling illicit and obscene material.

One day I dared to enter. The walls were lined floor to ceiling with books. It was overpowering.

‘Hello,’ said a gravelly voice. ‘Looking for anything in particular today?’

In the centre was a kiosk or booth where a man with a crumpled face and cola-tint spectacles sat reading a book. There were adult magazines in plastic wrappers hanging at angles around the top of the booth, a fringe of lithe tanned bodies and pouting mouths. There were more magazines heaped at the foot of the kiosk, but these were about motorcycles and cars. I replied that I was ‘just browsing’. The man coughed and went back to his book. There was a smell of cigarette smoke. Where would I find my quarry? I was shy and self-conscious. I didn’t want to ask the shopkeeper, although he seemed friendly enough. I ventured further into the gloom, into Literature.

My first purchases from Edward Terry were not The Profession of Violence and a copy of Knave but Great Expectations and Pride and Prejudice. I would have been sixteen. I bought them for my “A” levels. I still have those books. Hardbacks with faux-leather covers and ornate gold blocking – the sort of books that Peter Cushing, as Baron Frankenstein, would keep in his library. The Austen contains delicate illustrations by Sarah Archibald. It’s a sturdy volume. One of my pencilled notes states: “character develops through dialogue”. Great Expectations includes a leaflet proclaiming in orange and black type “THE CENTENNIAL EDITION of the works of CHARLES DICKENS presents GREAT EXPECTATIONS”. Both books were cheaper than the paperback editions I had been advised to buy. “Two great stories you got there,” said the man with the crumpled face as he wrapped them up in a brown paper bag I was too timid to decline. He had examined the books approvingly. With my Dickens and Austen in a suspicious-looking paper bag, I felt that I had moved into an adult world of books, a world unlike my own. This was a place where books were loved and remembered and considered as friends, as opposed to things to be studied and consulted.

I read the two novels over the summer. They were surprisingly enjoyable, especially the Dickens. But when I took out Pride and Prejudice in class, I felt uncomfortable, almost ashamed. The book looked too posh, even prissy, with its sky-blue ribbon and gold adornments on the cover. I felt as though I should be wearing a cravat and smoking jacket. A fellow student with inky fingers and gangly legs asked me where I had bought it. I explained, trying to sound casually streetwise, having purchased a smart hardback for less than his regulation paperback. He looked at me suspiciously. “Edward Terry?” he said. “That sells the mucky mags? Here, let’s have a look at those illustrations.”

About Stephen Hargadon

Stephen Hargadon's short stories – described by Helen Marshall as ‘wise, witty, and wonderfully dark’ – have appeared in magazines such as Black Static, Popshot and Structo. In 2017 he was shortlisted for Observer / Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism and was a runner-up in the Irish Post's 2016 short story competition. His non-fiction includes ‘Just Browsing’, a well-received essay on the joys of second-hand bookshops, published by Litro in 2015. He has just completed a novel and continues to write short stories. He lives in the north of England.

Brilliant nostalgia. Loved Edward Terry’s (or dward Terry’s as it was for its last 20-ish years after the “E” fell off).

Me and my mate used to visit every Saturday aged 10-11 fervently trying to add to our Stephen King/James Herbert collections.