You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

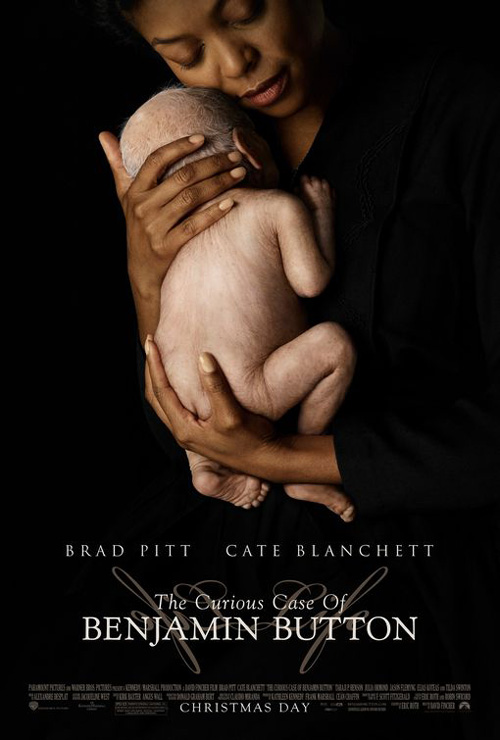

Go shopping Since Litro is focusing on the topic of film adaptations this month, I thought I’d write today about a recent instance of a film adapted from a piece of short fiction: The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I think it’s interesting because the relationship between the film and the short story really brought into focus for me how special the art form of short fiction can be, and how wonderful this piece is in particular.

Since Litro is focusing on the topic of film adaptations this month, I thought I’d write today about a recent instance of a film adapted from a piece of short fiction: The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I think it’s interesting because the relationship between the film and the short story really brought into focus for me how special the art form of short fiction can be, and how wonderful this piece is in particular.

I confess I’d never heard of Benjamin Button before the film came out. I’d read The Great Gatsby and it wasn’t really my thing, so I hadn’t investigated the rest of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work. I can see why people love Gatsby, and I think Fitzgerald is an incredible writer (I’m going to fawn all over him in a minute), but maybe the book’s reputation made me expect something different to what I felt I got. All the same, when the first trailer for the adaptation of Benjamin Button made its way onto my television set, I was instantly hooked by the concept. Then somebody told me about the short story, explaining that it was by F. Scott Fitzgerald (I couldn’t understand why this wasn’t announced in huge letters at the beginning of the trailer), and I shot off at once to the bookshop. I read the short story, then saw the film.

It was quite different.

I’m not criticising the filmmakers here, firstly because their movie had alerted me to something I absolutely loved, and secondly because there’s no way to make a faithful Hollywood movie of that short story. It has an aloof narrator (which is half the fun), and sweeps quickly through Button’s life, never getting bogged down in specific time periods, never concerning itself with fiddly details. I recently bought a compendium of American fairy tales, and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button would fit in tidily alongside Rip Van Winkle and the rest. It’s a perfect way to explore the exuberant conceit in the writing and you really sense Fitzgerald letting his imagination run riot. Once the concept is explored, the whole thing comes to an end. It’s a rock star of a story, burning brightly and then gone. A novel would get bogged down in storylines and characterisation, and there too is the rub for the film version: you can’t get Brad Pitt and the special effects budget you need for a Hollywood film if you’re not going to include any stories or characters. The filmmakers have instead bought the rights to the concept and done their own thing with it. The result is an interesting movie on its own terms, and like I say I’m not here to criticise it. It’s just that the story is absolute gold dust.

The thing I come away with from reading Benjamin Button is a sense that the process of ageing itself is strange and magical. It’s like that old riddle that asks what goes on four legs, then two legs, then three legs—with the answer being a person across the course of their life. Like the riddle, the story draws parallels between the infirmities of infancy and old age. Button’s life is actually not so very remarkable, even though it’s being lived backwards. The beauty of experiencing this in short fiction though, is that you can hold the full biography of a life both extraordinary and ordinary in your head without more and more detail barging in to confuse it. It’s a supreme example of what the short story can achieve, and if you haven’t already done so I would urge you to give it a try.

About Ali Shaw

Ali Shaw is the author of the novels The Man who Rained and The Girl with Glass Feet, which won the Desmond Elliot Prize and was shortlisted for the Costa First Book Award. He is currently at work on his third novel.