You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping In the first of a series of plugs for my favourite short stories, this week I’m enthusing about Penelope Fitzgerald’s “The Axe”. Managing to be funny and genuinely creepy all at once, it’s a story where the mundane minutiae of office politics grumble steadily towards a lip-licking but nasty dénouement.

In the first of a series of plugs for my favourite short stories, this week I’m enthusing about Penelope Fitzgerald’s “The Axe”. Managing to be funny and genuinely creepy all at once, it’s a story where the mundane minutiae of office politics grumble steadily towards a lip-licking but nasty dénouement.

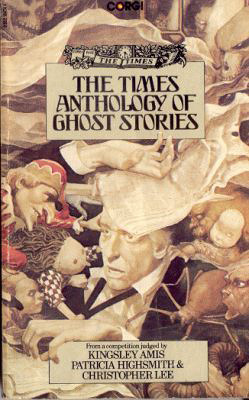

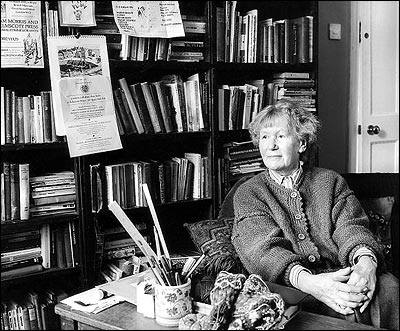

Fitzgerald entered “The Axe” into a ghost story competition run by the Times in 1974. It didn’t win first prize (although I think it’s much better than the story that did), but it was selected with twelve others to be published in The Times Anthology of Ghost Stories the next year. Fitzgerald was unknown as a writer at the time. She published her first book in 1975, a biography of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, at the age of 59; and her first novel two years later. I love it when an author I admire turns out to have made it big only later on in life. It’s much more inspiring (and reassuring) than tales of twenty-somethings striking three-book deals.

The Times anthology is an interesting collection in itself, containing also a first publication for another now famous writer, Julian Barnes. But it’s Fitzgerald’s story that stands out for me. Sebastian Faulks wrote that reading Penelope Fitzgerald “is like being taken for a ride in a peculiar kind of car. Everything is of top quality—the engine, the coachwork and the interior all fill you with confidence. Then, after a mile or so, someone throws the steering wheel out of the window.” “The Axe” is a good example of her ability to completely disquiet the reader.

The first great thing about the story is its structure. It’s a letter that starts abruptly, mid-sentence—a meandering, confusing sentence at that, full of business jargon that loses its meaning in a jumble of commas, hyphens and sub-clauses. The intended recipient seems to be the board of an unnamed company; the writer a middle-manager who has been asked to make redundancies. Specifically, he has been told to put his assistant, W. S. Singlebury, out of a job.

That name, with its precise and insistent initials, encapsulates the character of the man who becomes the initially pathetic but quickly menacing heart of the story.

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, he wore a blue suit and a green knitted garment with a front zip. On Tuesdays and Thursdays be wore a pair of grey trousers of man-made material which he called ‘my flannels’, and a fawn cardigan. The cardigan was omitted in summer.

The socially awkward situation that develops, in which the narrator alternates between sympathy for Singlebury and embarrassment at the man’s abject failure to deal with the loss of his job, crawls towards a grisly conclusion.

The socially awkward situation that develops, in which the narrator alternates between sympathy for Singlebury and embarrassment at the man’s abject failure to deal with the loss of his job, crawls towards a grisly conclusion.

Less adventurous writers of ghost stories might let their plots cower unadventurously in run-of-the-mill cobwebby castles or creaky manor houses, but a modern setting can make a good ghost genuinely unsettling, as the unfamiliar becomes the uncanny. (The Freudian concept of the uncanny, das unheimliche, is that of the familiar turned strange.)

“The Axe” is great. Track it down and devour it. The Times Anthology of Ghost Stories is pretty easy to get hold of secondhand, or the story can be found in Penelope Fitzgerald’s collection The Means of Escape, which is still in print.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.