You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

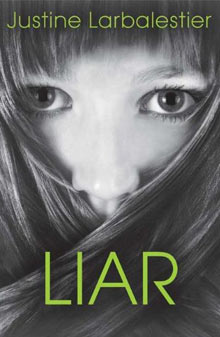

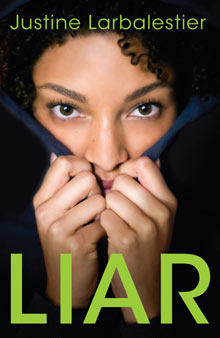

The big news in the book industry this week has been Bloomsbury’s cover design for Liar by Justine Larbalestier. You can read all about it here, but if you’ve missed the furore it can be summed up briefly like this: the book is about a short-haired black girl, and Bloomsbury’s original cover design showed a long-haired white girl. Bloomsbury has been accused of racism and has come under a great deal of criticism. They argue that they weren’t attempting to illustrate the lead character, but portray the tone and feel of the book. The other day they backed down over their cover design and released an image that better illustrates the lead character.

A lot has been written about this already, so I’m not going to talk too much about this specific case. I think alongside the racism debate, this incident demonstrates how strongly we feel as readers about the relationship between books and their covers. I think the old adage about not judging a book by its cover is only useful when thinking about things that aren’t actually books. Cover designs are an enormous part of the book industry. Huge amounts of effort and resources go into persuading us to judge what’s inside by its cover. This is because covers are more comparable to set designs than something like sleeve art on albums. They’re an integral part of the physical act of reading a book. You’re unlikely to hold sleeve art in your hand every time you listen to a record, but if the image you look at every time you open the book you’re reading feels false, it can have a jarring effect on what you’re reading. I can understand why publishers often opt to avoid images entirely and stick with abstract or plain designs, as this plays safe with the reader’s sense of how the book feels.

We’re visual beings, and our imaginations are easily influenced. You know that peculiar way an actor in a film adaptation of a book can dislodge the image you formed yourself of a character? I think the wrong cover can mess up the visual tone of a book in the same way. You can forget about it as the book absorbs you, but there’s that jarring image again the next time you pick it up to read it. It’s a door through which you enter the book, and it can easily set the wrong tone. As a debut author I experienced firsthand the fear of seeing my book’s cover for the first time. A simple pdf attachment lands in your inbox, you hover your cursor over it and hope like crazy it’s going to complement your book when you open it. In my case I was absolutely delighted with the design, but my heart sped up as I double-clicked that attachment.

I’m sure not everyone is influenced so heavily by covers, but when I think of my favourite covers, I think about the effect they’ve had on my experience of a book. In some instances the effect has been enormous. I bought a version of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness when I was eighteen. It showed the head and shoulders of a bald man, one half of him brightly lit, the other in green, oily shadow. (I wish I could find a JPEG of the cover design for you, but have had no luck.) The portrait had been worked over with inky smudges and scratch marks, and in the middle of all this chaos and dirt was one illuminated eye of the man, staring right out of the cover at you.

I didn’t know anything about the book back then, but the image just stuck with me. Nor did I read the book for ages after purchase, although I kept pulling it off the shelf just to look at it. This ghastly, light-and-dark portrait became the first thing I thought about when I heard the name of the book or came across a nod to it in other places. When I watched Peter Jackson’s King Kong, there’s a bit where two characters on the ship suddenly talk about Heart of Darkness. And all of a sudden, even though there’s a giant cinema screen in front of me full of moving and talking pictures, the only one I can think of is this cover design. By the time I came to read the novel itself, the portrait haunted the contents. It was the emotional filter through which I absorbed everything in the book itself, and quite often I’d stop at the end of a passage, close the book, and just stare at the cover design.

If electronic book readers take off en masse, I’ll be the Luddite hanging around the printing press. Because it’s not just being able to see the book cover, it’s being able to take it around with you. I recently found a 1944 edition of Frankenstein that had been printed in Calcutta and had found its way (I wish I could somehow discover its journey) to a secondhand bookshop in the quiet Dorset countryside. The cover is a plain mahogany shade; it never had a cover designed for it. But here’s the thing: it’s faded in places, especially down the spine, and the title is not printed on the cover but on a peeling sticker, in suitably gothic script, affixed with dried-out glue. Best of all, something has gnawed one of the book’s corners, leaving the brown stitches torn and ragged. It smells of pipe smoke and sea salt. If it were another novel the book might seem damaged and dirty, but this is Frankenstein! For the story, the book’s condition is perfect.

I have a naive and romantic hope that the book industry might just use technology to follow a different path from the MP3 and the downloadable movie. Make more of books as objects, invest every new publication with a physical sense of the things the words inside make us imagine. These objects are things to celebrate, and if anybody fancies sharing their tales of books whose very appearance or production has influenced the way they’ve been read, I’d love to hear them.

About Ali Shaw

Ali Shaw is the author of the novels The Man who Rained and The Girl with Glass Feet, which won the Desmond Elliot Prize and was shortlisted for the Costa First Book Award. He is currently at work on his third novel.