You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

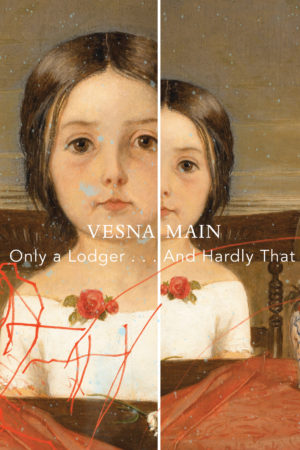

Go shopping“I am puzzled by narratives of belonging,” Vesna Main said in an interview with Elsewhere magazine, “I don’t think of home as a place, or a geographical region. Therefore, it can be anywhere and nowhere,” which is a good an introduction as any to her new novel, Only a Lodger … And Hardly That. The title’s borrowed from the eighteenth-century writer and composer Charles Ignatius Sancho, who gained notoriety as the first British African eligible to vote in a general election. Asked by his friend, Laurence Sterne, for an opinion on a particular political issue, he declined to comment, saying he was: “Only a lodger … and hardly that.”

Billed as a “fictional biography” (real or fictitious, we’ll come to that), the novel unpicks the lives of Main’s paternal and maternal grandparents in five separate stories. In the first, “The Eye/I”, the narrator reflects on what it means to retell one’s story. Is it possible to reduce pivotal moments from one’s past to explain personality: the kneeling on a sheet of white paper, a dislike of street urchins, an inability to memorise a poem? Were these the reasons the narrator ended up being a writer who fell in love with the dead Croatian poet, Antun Gustav Matoš?

The second story, “Acrobat”, is a lovely magical realism poem which tells of Maria’s encounters with the circus that did or did not come to town, the tightrope walker Fabrizzio she fell in love with (who flew or did not fly), and the wealthy older suitor she rejected in favour of marrying Francis.

The stories in “The Dead” and “The Poet” belong to the two grandfathers, Pavel and Francis. “The Dead” takes the form of a conventional memoir, describing Victor’s reinvention as Pavel, a home-schooled scholar, who derived pleasure from selecting and sending books anonymously to his granddaughter, the narrator of “The Eye/I”. Borrowing from Sebald, “The Poet”moves seamlessly between personal history and the wider cultural context through a series of family photographs Main compares to paintings by Leonardo Da Vinci and Edouard Manet.

In the last story, Gustav Otto Wagner, Maria’s spurned suitor, offers an outsider’s view of the Ondruš family. Besotted and beguiled, he sits with his apple strudel in the same café where Maria fell in love with the famous dead poet, Matoš, pondering the origins of Maria’s mysterious illness; whether it was caused, as her father said, by an incident at the circus which did or did not come to town.

Throughout the novel, Main employs recurring motifs to connect and deepen the narratives – Matoš’s famous poem, “The Consolation of the Hair”, white collars and white gloves make their presence felt down the years. Fact and fiction blur: the paper, the poet and the gloves are real; Pavel’s identity is borrowed; the acrobat exists only in Maria’s mind. The past cannot be pinned to a singular narrative, it belongs to many voices, has many interpretations, and many ways of telling. And this is the novel’s beauty: a fictional biography that belongs to a fictitious narrator who grew up, like Main, in Croatia; who, also like Main, loves the English language and studied Shakespeare. What difference do facts make to history? Main appears to ask.

Only a Lodger… And Hardly That is both a search for identity and a rebuttal that such a search could yield any meaning. Belonging and alienation exist side by side. In the Elsewhere interview, Main also said: “None of the characters I create in my novels or short stories is me, but I share with them their sense of alienation, the feeling of being citizens of everywhere and nowhere.”

The language is playful, sometimes dense, but always intelligent and original as Main dips in and out of the authorial voice, subject and observer. The stories can be enjoyed in their own right, but sequentially, they form a substantial work; a book which travels far beyond nineteeth-century Mitteleuropa to probe the meaning of our place in the world today; the fragile foundations that shape identity, whether chosen or inherited.

Only a Lodger . . . And Hardly That is published by Seagull Books.

You might also like these short stories written by Vesna Main, My Sinister Side and Live and Let Live.

About Christina Sanders

Chris Sanders has been writing short stories for over ten years. She has been published in: Writing Women, Quality Women’s Fiction, Peninsular and TQF. In 2011 she won an Arts Council bursary to appraise her first novel, and has contributed to various Arts Council writing projects. At present she is working to complete a collection of short stories on the theme of ‘Compromise.’ Chris Sanders holds a Masters in Education, and is currently working with women from BME communities in Hastings to use storytelling as a way to explore identity and heritage.