You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingJust a little over halfway through Erik Martiny’s debut novel, the protagonist-narrator, Olaf Montcocq, deep in the throes of adolescent literary self-emergence, explains how he welcomed the prospect of being sent abroad for a year as a teenager “to experience another school system, get a fresh perspective on things and learn to be more autonomous.” While he is “not too eager to leave Ireland just yet”, he says, “the prospect of being able to write an entire short story in peace, of having a whole room to [himself] and not having to queue makes [him] finally agree to set off for France”.

By the time the reader gets to this point in Martiny’s highly entertaining and fast-paced narrative, one realises that it is, for all of its comic high jinks, an intellectually engaged and engaging work. This is to be expected given Olaf’s immediate family background – his father is a professor at University College Cork in the south of Ireland – but Olaf is himself also an academic in the making. He is a literary scholar, to be precise, though he is also tormented (as many literary scholars are) by the desire to make art. So we encounter Olaf, towards the end of the work, in a situation where he has “read so many articles, gargled so much jargon, that there’s a knot in [his] tongue and a crumpling in [his] soul.” In a sense, then, The Pleasures of Queuing is a book about what happens when one attempts to untie this “knot”: to unravel and tease out the strings that bind and sometimes restrain the discourses of “literature” and “criticism” as they relate to each other.

There are many ways in which this project could have been undertaken. From Terry Eagleton’s The Function of Criticism (1984) to Rónán MacDonald’s The Death of the Critic (2007), many influential literary critics have sought to critique the institutions and practices of criticism from inside the academy. Writers have done it too, of course, and the list of novels in which academia provides both setting and theme is a long one, including some of the best novelists of recent decades, such as Michael Chabon, Jeffrey Eugenides, Julie Schumacher, Donna Tartt, and John Williams. Martiny’s book, from its opening pages, is an uproarious and irreverent exposure of male literary self-consciousness, not just within the academy but within the home. Olaf’s desire to find “a whole room to [himself]” is a clear allusion to Virginia Woolf, for example, who wrote that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” in A Room of One’s Own (1929). Olaf desires a room because he cannot find space to write in the house he shares with his parents and several siblings, but his need to have “a whole room to himself” reflects a hilarious lack of self-understanding on the part of the protagonist. In the character of Olaf, in other words, Martiny satirises the male academic author for whom the ghosts of Woolf, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and many others, are conjured as reassuring presences in a personal pantheon that serves no other purpose than to boost the protagonist’s ego.

This is hard on Olaf – it is not at all clear that he ever really gets it, even after the ghosts of these and other writers appear before him to offer advice in the final episode of the novel – but how else should one take this character and the accounts he gives us of his various adventures in living “the literary life”? Granted, these are funny, often darkly so, and Martiny has a knack for comedy that often produces side-splitting results. “When all is said and done”, however, as Olaf says at one point, “it is our father’s reading of Camus and the experience of enduring fleas that makes me want to become a writer.” He continues: “Writing seems like the perfect way of turning bad into good, pain into pleasure, weariness into wonder, a way of transmuting shit into gold when shit happens as it inevitably does”. There is still an awful lot of “shit” to be processed in Olaf’s life – and in the world around him. Each chapter of the book begins and ends with a list of shitty historical facts – “The USA, the USSR and France test nuclear missiles […] Charles Manson is convicted of murder”, for example – but these are scarcely registered by Olaf or those around him, whether in the home, at university, or anywhere else. Instead, we are told by Olaf early in the narrative that these are nothing more than “short French news bulletins provided in translation [as] condensed samples of the informative noise pollution that pervades [the] house in Bishopstown, County Cork, Ireland” where the Montcocq family resides.

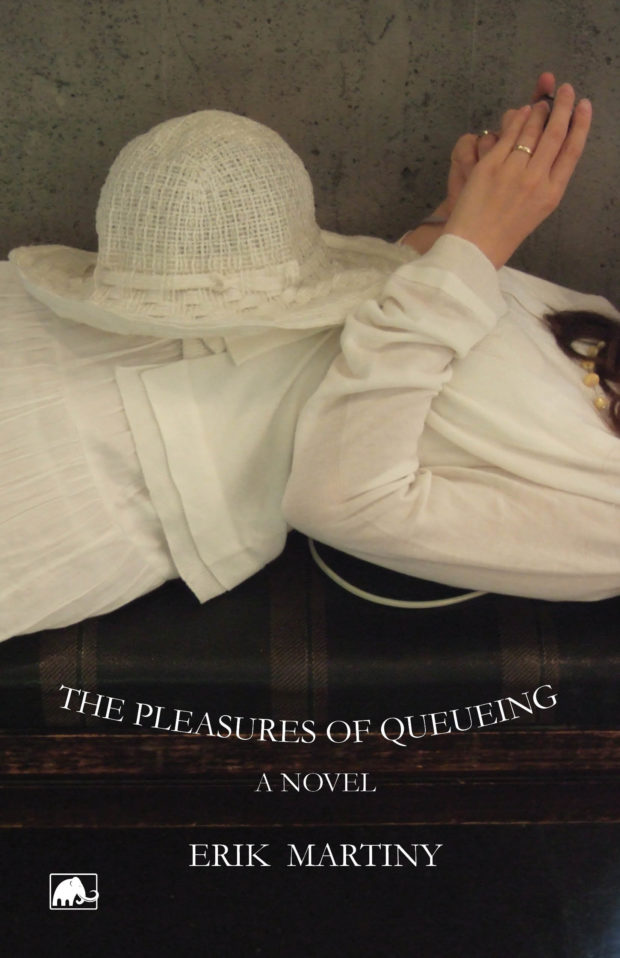

What we have here, in other words, is a seriously funny novel that wants us to take seriously the fact that it is funny – without being too serious about it. It could be an error, but at one point in the text the narrator imagines the reader wondering “[w]here, if anywhere, is this factional memoir even going?” (emphasis added). If The Pleasures of Queuing is “factional” – not “fictional” – then it is one of the most candid literary autobiographies ever written. Whether it is a work of pure fiction or not, however, it is undoubtedly one of the funniest narratives to be written in recent years about growing up and coming-of-age in the south of Ireland in the last few decades of the twentieth century. It has parallels with the works of contemporary Irish writers such as Kevin Barry and Julian Gough, but its world ultimately extends beyond Cork, out into the broader Irish and, indeed, Franco-Irish cultural and social sphere of reference and beyond – and back again, into the “small republic” of the family. That term (“small republic”) belongs to John McGahern, whose work provides one of the epigraphs to The Pleasures of Queuing, but it is given new life here in a novel that seems destined to become some kind of cult classic.

The Pleasures of Queuing is out now from Mastodon Publishing.

About Philip Coleman

Philip Coleman is an Associate Professor in the School of English, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.