You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

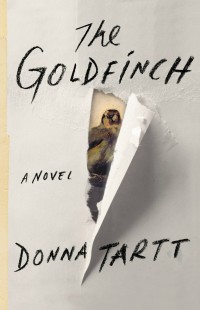

Donna Tartt’s latest novel is a Bildungsroman in all its coming-of-age glory, as Theo Dekker works his way through a world as messy and disorientating as our own. After an explosion in the city-machine of New York kills Theo’s mother, his estranged father comes to reclaim him from the arms of the Big Apple’s elite. He is relocated to the eerie suburbs of Las Vegas with nothing but a stolen painting of a goldfinch to remind him of the life he once led. The recognisable clutter and confusion of everyday life are perfectly captured, intensified through the unease of a young boy in the wake of loss.

The stolen painting, while central to the narrative, often fades into the background of Theo’s life. I found myself forgetting about it altogether—as Theo occasionally does—so absorbing is Tartt’s evocation of the semi-deserted Las Vegas suburbs. When Theo befriends the “Barbarian Prince” Boris—a Russian Artful Dodger to Theo’s displaced Oliver Twist—the painting is disregarded completely as Theo attempts to negotiate the complexities of his new life, egged on by his charismatic new friend.

You can look at a picture for a week and never think of it again. You can also look at a picture for a second and think of it all your life

Along with The Luminaries, The Goldfinch cemented 2013 as a year for beautifully written but vast novels. The Goldfinch is around eight hundred pages long, and part of the joy of reading a book so expansive is the devotion it demands and it is rewarded. Years pass, characters grow, we are swept away with the bit-part players that come and go in Theo’s life.

Some critics, presumably desperate to analogise, have discussed Theo as a Harry Potter figure; he is the ‘boy who lived’ indeed, but hardly a wizard out to fight evil. He’s far too complex for such a fairytale comparison. Those who have heralded the work as Dickensian are closer. It’s easy to see The Goldfinch as a reimagined Great Expectations, for part of the fascination of this novel is in the sheer detail of every character Tartt creates. Every person in the novel is fully formed, from walk-on eccentrics to major players., The bit-parts delight because, dropping in and out over hundreds of pages, they take on roles rarely captured well in a novel: casual acquaintances, rarely-seen friends. The people who become significant with time, not because of the contrivances of plot. It’s rare to find a writer who spends so much time becoming acquainted with every cast member; rare still for such attention to detail to be so invigorating.

Theo’s impetuous you-only-live-once theft may represent the promise of the present, but The Goldfinch is also concerned with the past, and the manner in which memories shape us, often while we are unaware. In the book’s opening passage Theo dreams of his mother, who represents an alternative world: another life in which he might remain secluded and happy, content in the big city, visiting art galleries, casually devouring culture and appraising antiques. But with his mother only a memory, these things are distorted. The painting of the goldfinch represents impulsive youth but is also a last thread of what-could-have-been. Folded up and secreted in a pillowcase, the painting becomes a guilty secret which taints event positive memories. The tender passages detailing Theo’s final moments with his mother are beautifully sad but what the reader wonders about most is what will become of the stolen painting, the painting that Theo has yet to understand and maybe never will.

Every new event—everything I did for the rest of my life—would only separate us more and more: days she was no longer a part of, an ever-growing distance between us. Every single day for the rest of my life, she would only be further away.

This story will change you, mostly because of its honesty. After you’ve read it, you’ll remember sections as though you’re recalling something a friend told you about. How that one time he had to take a coach journey with a dog; how petrified he was that it would annoy someone and he’d be thrown off. Even such apparently mundane moments are suspenseful, and take on a wonderful clarity at Tartt’s touch. There’s an eloquence in the most trivial events. It should come across as self-indulgent, but it ends up being deeply moving. We see the world from Theo’s perspective and Tartt never lets the mask slip for a moment. We are fixed in the world of the protagonist.

In a very real sense, the world of The Goldfinch has its limits; The0 is not an omniscient narrator and it is intriguing how little we learn about the places through which he passes. We see a lot of his world, yes, but Theo, like most of us, spends a little too long in the past, in his own head, to be overly concerned with clearly detailing the present. He looks inward. It’s an expected reaction to loss for someone so young, but a brave feat for Tartt to pull off in a novel that spends so long with a single narrator. For instance, rather than fleshing out pages with gory details of the attack that killed Theo’s mother—of how and why the bombing occurred in the first place—Tartt keeps us in the dark. Theo doesn’t care for the details; he’s got bigger things on his mind. His mother is his world—was his world—the details of who exactly attacked the gallery and for what purpose are inconsequential: what’s done is done. The world outside his head is distant, nothing but a memory.

In a very real sense, the world of The Goldfinch has its limits; The0 is not an omniscient narrator and it is intriguing how little we learn about the places through which he passes. We see a lot of his world, yes, but Theo, like most of us, spends a little too long in the past, in his own head, to be overly concerned with clearly detailing the present. He looks inward. It’s an expected reaction to loss for someone so young, but a brave feat for Tartt to pull off in a novel that spends so long with a single narrator. For instance, rather than fleshing out pages with gory details of the attack that killed Theo’s mother—of how and why the bombing occurred in the first place—Tartt keeps us in the dark. Theo doesn’t care for the details; he’s got bigger things on his mind. His mother is his world—was his world—the details of who exactly attacked the gallery and for what purpose are inconsequential: what’s done is done. The world outside his head is distant, nothing but a memory.

To understand the world at all, sometimes you could only focus on a tiny bit of it, look very hard at what was close to hand and make it stand in for the whole…

In this way Theo becomes the Goldfinch of the title. A small lonely bird, tethered by a chain he does not see, attempting to spread his wings in a world he does not understand. It spoils nothing and comes as no surprise that Theo outlives both his parents. His inability to unfetter himself from such experiences shapes the novel. Theo never actually gets to leave the nest at a time of his own choosing; instead, he is thrown from it. He is without shelter and he cannot fly.

At times it seems as though Tartt is in danger of overreaching. The Goldfinch is long, varied, spread across all corners of the Earth, involved with all classes and all manner of social situations. It is a novel about relationships in all their stages, all their forms, making, breaking, reviving, consuming, abusive, obtrusive, elusive. Yet through this confusion there is a thread of clarity. The aspects of the novel that could have been its weak points are actually its strongest: its size, the inwardness of its narrator, its eclectic cultural references. The Goldfinch will leave you exhausted, both from carrying it around and from the mental energy Tartt demands that you invest in her characters. This is a book that calls for complete immersion—but it is well worth the effort.

A great sorrow, and one that I am only beginning to understand: we don’t get to choose our own hearts. We can’t make ourselves want what’s good for us or what’s good for other people. We don’t get to choose the people we are.

The Goldfinch is available now. Buy it from Foyles.

About Thea Hawlin

Theodora (Thea) Hawlin is assistant editor and production manager of The London Magazine.

We have been knowing of the way to get the fifa game. https://fewcheats.com/fifa-19/