You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Marginalia, notes or scrawls in the margins of a book, have always intrigued me. On the one hand, they are the literary form of graffiti, vandalisation of the printed page that shows a writer undermining or mischievously subverting the primary author, adding comments to cock a snoot at the wisdom of the original. On the other, they are the utmost in veneration, a sign of scholarly, academic study and proof that the subject matter is suitably lofty to require reasoned annotation.

Marginalia, notes or scrawls in the margins of a book, have always intrigued me. On the one hand, they are the literary form of graffiti, vandalisation of the printed page that shows a writer undermining or mischievously subverting the primary author, adding comments to cock a snoot at the wisdom of the original. On the other, they are the utmost in veneration, a sign of scholarly, academic study and proof that the subject matter is suitably lofty to require reasoned annotation.

As such, the ambiguous nature of marginalia often points more to fiction than fact but this contradiction is not something that mainstream writers often broach, tending as they do to favour simple, linear writing. Beginning…Middle…End – so the thinking goes. You don’t see many people frantically annotating their copy of Fifty Shades or the Da Vinci code after all.

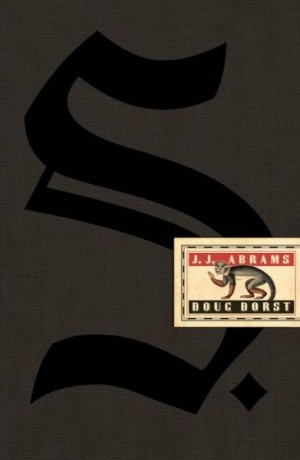

All of which makes it something of a surprise to come across S a collaboration between Hollywood producer/creator JJ Abrams and author Doug Dourst. A mainstream heavy hitter by any standards, Abrams is currently directing the new “Star Wars” film having created the hit T.V series “Lost” as well as directing two “Mission:Impossible” films, while Dorst’s 2009 novel, “Alive in Necropolis” received widespread acclaim and solid sales.

Meta- codex

The first thing to mention about the book is that it’s “production value” is second to none. In the world of ever tighter margins this book pulls out all the stops from a design and publishing perspective. Not only is the material beautifully designed but the layout suggests that serious thought has gone into the way it all hangs together. But more on that later, suffice to say if this was a movie it would be big budget.

Upon opening the package, the first curiosity is that the only mention of the real authors names is on the cardboard sleeve in which the “book” arrives. Inside this sleeve the reader discovers what appears to be an old, much thumbed hardback library book called the Ship of Theseus, written by V.M. Straka.

“If there is a category of skulduggery to which Straka’s name has not been linked in the popular press (and in some infuriating articles passed off as “literary scholarship”), I am not aware of it. Perhaps this is to be expected as Straka’s work itself often included secrets, conspiracies and shadow-world occurrences.”

A translator’s note introduces Straka as the eminent author of the tome and alludes to his mysterious disappearance prior to completion of this translation. Alongside the text of his moody story are variously coloured margin notes from two students, Jen and Eric. The fact that this is a library book suggests they have both returned to check the book out various times.

Their scribblings are rendered in high quality giving the impression that a real human hand has written with biro or pencil and it is only the lack of indentations that identify the script as printed. To make matters more cryptic Jen and Eric not only reference the text but correspond with each other, flirting back and forth while chewing over the mystery behind Stark’s disappearance years earlier.

This in itself is a fresh enough quirk but within a few pages the second unusual feature of the book falls into the readers lap in the form of a folded note, presumably left there by either Jen or Eric or some other earlier reader. As the story progresses the reader uncovers more and more ephemera, interleaved at relevant points in the story. The various timelines interlink as Straka’s gloomy seafaring tale is annotated by the two investigators who query the facts behind the original Eastern European author’s intents and life.

Style over substance?

The book while exquisitely packaged is very difficult to assess on a purely literary basis. It feels as much an experiment in design, book-binding, and packaging as an experiment in words. And while this in itself is no bad thing it makes for an ultimately unsatisfying read in places.

Taken together the various meta-gimmicks and sophistry create something of an over-whelming experience. The sheer number of inserts makes it difficult to read without markers and folded pamphlets falling out. It is not the sort of book to stuff in your bag to read on the tube.

“Some time ago, when S still cared about where the Winter City might be, relative to the world of which the newspaper speaks, he formulated a theory: while the Winter City is of the world, it is not, strictly speaking in it. You certainly can’t get there just by sailing your ship into the low latitudes. The Winter City is neither above now below nor parallel to that world. The Winter City is, and the familiar world is, and they are in some proximity to each other, though perhaps not always.”

Dourst is an atmospheric writer and the central story has shades of Onetti’s the Shipyard and obvious nods toward the writing of B. Travern, however the sheer inundation of information in the side notes works against engagement with the tale.

Is there a reason that Jen and Eric write in five or six colours of biro? I’m sure people do use orange, purple and green pens occasionally but the constant switching suggests they should probably buy pens with more ink.

What is worse the vast majority of correspondence between Jen and Eric comes across as irritating chit-chat completely unrelated to the main text. They are purported to be bibliophiles but rarely does their conversation digress from inane gossip and enter any deeper discussion of literary merits.

“Don’t you think we should get together and talk? At least to figure out what to do with the Filomelo info?

You’re probably right.

Good. Tomorrow @ 9pm. Coffee at Pronghorn Java. Ok?

Ok.”

Why does Eric ask Jen out for a coffee by writing a margin note? Would it not be easier to simply leave a note with the librarian seeing as they seem to be checking the book out so regularly? Or maybe write an email address?

When they are not flirting they sound like two over excited teenagers texting. While realistic enough their chatter does nothing to deepen the mystery but simply acts as a distraction, bogging down the flow of the book.

A strike for the printed word or the first stage of in-book advertising?

Despite these niggles there is something endearing about S and the premises behind it as it raises pertinent questions about the way we understand literature. It is certainly not a new idea that the way we read is changing, the rise of the e-reader has destroyed sales of ‘traditional’ books, and experiments such S seem designed to make us question what it is we really value about the printed page.

In this new world, annotations and margin notes seem to take a new significance. The cloud now means that everyone is able to share their thoughts on any given text with the rest of the world instantaneously. Just read “Dead Souls” and want to add your tuppence worth? No problem. Want to see what someone else thought of “Dead Souls”? Just click.

The cloud can in theory, link every copy of an ebook, creating a single connected text. Your margin notes instantly shared with anyone in the world reading that text. It took the introduction of e-reading for the first serious research on the subject to be conducted. Still it remains to be seen what this means for the way we communicate and interact with new ideas.

One can’t help feeling that the true value of a literary text is inherently abstract – good literature is an inter-relation of words and should make presentation or form irrelevant. Books are not “good’ because they are books, but because of their contents. What value does a beautifully made book provide beyond that of a beautifully made toaster, vase or pair of shoes?

Having said that, anyone with even a passing interest in reading can scarce deny that there is a distinct pleasure in reading a good story from a well presented page. E-Readers may be lightweight and useful but they cannot replace the feeling of turning the pages in a book and the exquisite packaging of ‘S’ certainly makes a strike in favour of the printed word.

It also opens up new possibilities for less appealing forms of engagement. The idea of material inserted at key points in a narrative, relevant to the story taking place on the page and designed to engage the reader sounds too much like a description of advertising to ignore. With sales numbers dwindling how long is it before publishers solicit in text advertising?

True it is unlikely you will see much relevant context for adverts in “Dead Souls” but I’m sure Ann Summers would be interested in inserting a few contextually relevant flyers in the multi-million selling Fifty Shades of Grey.

S was published in October 2013. Buy it from Foyles.

About Lochlan Bloom

Lochlan Bloom is a British novelist, screenwriter and short story writer. The BBC Writersroom describes his writing as ‘unsettling and compelling… vivid, taut and grimly effective work’. He is the author of the novel The Wave as well as the short fiction pieces – Trade and The Open Cage. He has written for IronBox Films, BBC Radio, Slant Magazine, Litro Magazine, Porcelain Film, EIU, H+ Magazine and Calliope, the official publication of the Writers’ Special Interest Group (SIG) of American Mensa, amongst others

It was all we were looking for.