You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

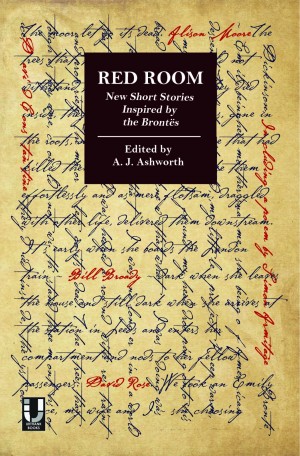

Go shopping Red Room is a slender volume, which feels longer than it looks. Each of the twelve short stories, written by fairly well-known and prize-winning authors, was inspired by the life or writing of a Brontë sister (half relate to Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre). It seems the idea was to give the writers a relatively free hand: the stories are set from the 19th to the 21st centuries; some imagine how the real-life authors could have acted or spoken, others extend a Brontë work in a new vein or depict Brontëesque characters; some are realistic, other fantastic. Write a short story, don’t make it too short or too long, think of at least one of the sisters: result.

Red Room is a slender volume, which feels longer than it looks. Each of the twelve short stories, written by fairly well-known and prize-winning authors, was inspired by the life or writing of a Brontë sister (half relate to Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre). It seems the idea was to give the writers a relatively free hand: the stories are set from the 19th to the 21st centuries; some imagine how the real-life authors could have acted or spoken, others extend a Brontë work in a new vein or depict Brontëesque characters; some are realistic, other fantastic. Write a short story, don’t make it too short or too long, think of at least one of the sisters: result.

The collection’s name comes from Chapter Two of Jane Eyre, during which the heroine is locked away as a punishment and endures a spell of fervent imagination – is at turns playful and serious. “Chapter XXXVIII – Conclusion (and a little bit of added cookery)”, by Vanessa Gebbie, for example, takes great pleasure in imaging what could have happened if Jane and Rochester had not married in Jane Eyre. “Reader, I did not marry him”, the story, predictably, starts. Gebbie’s Jane is amused and self-confident; her Rochester one could imagine clocking The Great British Bake Off:

“[He] continued cooking until his concoctions were the talk of society. Oh, yes, he was completely blind for the first two years, and, occasionally, mistook ingredients, with the most amusing results. His sardine and raspberry soufflés, sent to Blanche Ingram’s for her wedding, caused mayhem, but then she always needed a rocket up her bustle, don’t you think?”

Gebbie, in the useful “Inspirations” appendix, says she had great fun in writing the story and hopes it will make us “giggle as much as its writer did when creating” it. That depends; not all readers enjoy essentially light-hearted takes on what was intended to be deeply serious (not dull, you understand). The story might make many smile, and others grimace.

Playfulness also drives Tania Hershman’s “A Shower of Curates” and Zoë King’s “My Dear Miss…”Hershman, the editor of The Short Review, takes all the first lines of the Brontë novels to use them as prompts. It’s verbally inventive, switching from one thing to another, effervescent if not especially meaningful and brings to mind Samuel Beckett’s dramatic monologue Mouth (1972): a vague but intense narrator speaks a stream of phrases that make sense individually, but the meaning between which is as obscure as it is intriguing:

“Ah now, that is better, the draught has done its work, its holy work, yes! I am a one for that kind, I am that since – well, if you must know that you must go back with me to the autumn of 1827, stretch yourself to parse that far, that ancient year, before all that we now know, all that we grasp as essence, as import. My godmother lived in a handsome house in the clean and ancient town of Bretton….”

Zoë King, the ex-editor of Cadenza, conjures up Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre as correspondents. The subject of their letters is romance: whom to marry or avoid. King explains the idea came to her from an exercise she used with her writing class: imagine two fictional characters in conversation across the bookshelves in a library late at night. As with Vanessa Gebbie’s story, Hershman and King’s efforts won’t appeal to everybody, but they’re good-humoured and inventive.

Rowena Macdonald, in “A Child of Pleasure”, is more self-consciously serious-minded. Taking her inspiration from Charlotte Brontë’s Villette – specifically, from the relationship between Lucy Snowe and Ginevra Fanshawe – Macdonald’s story sees a lower middle class tutor help prepare a rich young girl for her English A-level. Things quickly go beyond education, which the girl isn’t interested in anyway, instead turning into the tutor’s efforts to improve the girl ethically. The tutor has a purely negative view of the girl’s parents: the mother is a successful businesswoman who can only speak the language of money; the father is first seen in…

“…a basement kitchen of marble and steel, where [he was] lounging at the dining table with a G and T and the FT.”

Clearly a wrong ‘un! The girl at first laughs at and then simply ignores her tutor; worse, her narcissism actually proves to be a successful technique in dealing with her world. “A Child of Pleasure” is technically efficient and ends well. But its portrayal of the rich is stereotypical and even distasteful; the perception of successful businesswomen as heartless robots, which has a long, notorious history, is unfortunate. Ideologically the story, just as Macdonald’s “Burning Man” in Unthology 4, comes in the wake of the Great Recession; your response to it will likely be informed by who you blame for that.

Most of the serious-minded stories portray passionate, outwardly quiet characters. The focus is on the telling narrative detail and frequent lyricism. “Ashton and Elaine”, by David Constantine, inspired by Wuthering Heights, concerns a young boy who can barely communicate until he meets Elaine and her family. The moors east of Manchester, scene of a family outing, is beautifully described:

“The children turned and waved…across the sunny slope, its textures of black and brown and many greens, its vigorous yearly renewal through the blonde dead grass, the bracken unfurling, the scent-dizzy bees in the heather, the black groughs, gold gorse, soft white cotton grass and, from where the children stood, the untold acres of ripening billberries.”

This passage is neither playful nor underpinned by an egalitarian ideology, but instead exults in natural beauty, which provides a timeless backdrop to the human drama unfolding within it.

Two stories stand out for their impact: Alison Moore’s “Stonecrop” and Carys Davies’ “Bonnet”. Both are relatively brief, three and four pages respectively, but use the short story’s strategy of revealing a lot with a little especially well. Both writers have an elegant touch.

“Stonecrop” was inspired by a line from Wuthering Heights: “After all, she was a sweet little girl.” In the story, the quiet Catherine gets a new stepfather, Mr Blakemore. A control freak, Mr Blakemore’s fortune are swiftly reversed by his “sweet” stepdaughter; a few hundred words are enough to change his entire lot.

“Catherine was given sweet, black tea. She was required to talk about what had happened, but she could not remember very much, and that was, said her mother, said Catherine, because of the shock.”

Davies’ “Bonnet” imagines a meeting between Charlotte Brontë and her publisher George Smith. Davies speculates the author was deeply in love with her publisher, and that the latter knew this. In the “Inspirations” appendix, Davies quotes a letter from Charlotte to Smith to congratulate him on his engagement to the daughter of a wealthy wine merchant, which reads, in full:

“My dear Sir,

In great happiness, as in great grief – words of sympathy should be few. Accept my meed of congratulation – and believe me

Sincerely yours,

C. Brontë”

“Bonnet” sees the author go down to London to meet Smith, buying a new bonnet in the city to impress him. As she does so, she has to take off her travelling bonnet; we’re told, in a fine touch, that she feels naked without it and wants to borrow one until her new purchase is ready. On meeting Smith, now wearing a bonnet with lustrous pink lining, the narrator tells us that, “It is the worst imaginable thing, when he looks up, for him to see it; for him to see this small plain woman, his friend, with this unexpected bonnet on her head.”

Red Room feels longer than it is, due to its variety and frequent impact. There is something for most readers, from light-hearted creative writing exercises to powerful vignettes and character driven stories. What runs through most of the pages, certainly the best ones, is a sense of emotional turbulence. The best achieved fictional worlds here are driven by passion, a socially undemonstrative but spiritually strong sense of being, which more often than not finds its bearings in a persistent desire for more.

About Andre van Loon

Andre van Loon is a freelance literary critic, specialising in new British and American novels and studies of Russian nineteenth century literature. He holds an MA in English Literature & Russian Studies from the University of Edinburgh and lives in London.