You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

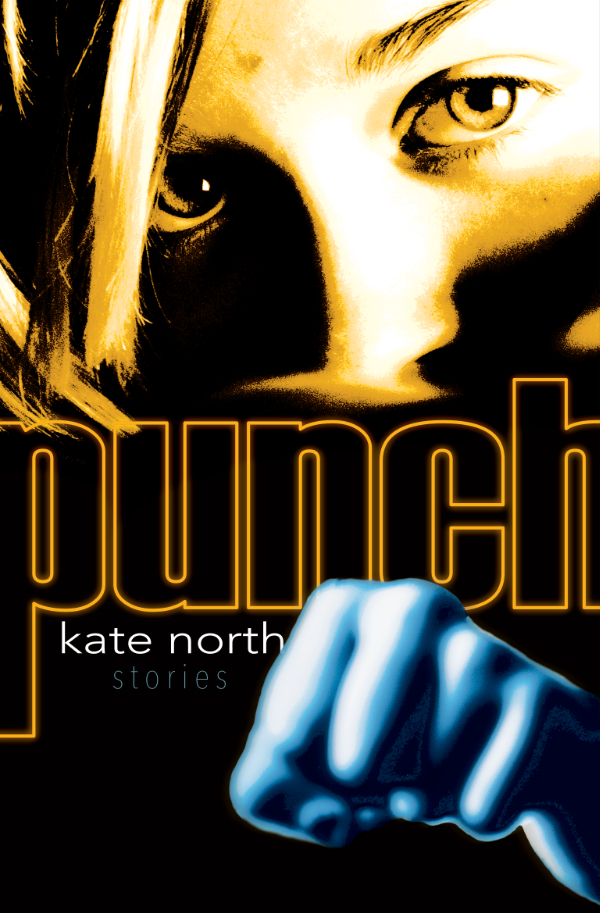

Cars, restaurants and foreign travel feature heavily in Kate North’s new collection of short stories. A mask on a wall of a rented villa speaks out, a car and van collide on a roundabout, a couple sit in a Venetian trattoria discussing Pope Pius’s penis. Characters are routinely displaced and forced to negotiate unfamiliar situations. Over one third of the stories are set abroad, while those closer to home focus on the unfamiliar, the sudden losses or discoveries which unsettle and expose the hotchpotch of emotions simmering below the everyday calm. A few push beyond the commonplace into the realms of the surreal. In “Fifteen Arthur Crescent”,a couple move into their “bargain” new house to discover disappearing ladders, walls which stencil themselves and underwear mysteriously relocated. “Lick”follows a male protagonist who wakes after his thirtieth birthday to find a lump on his hand. Embarrassed rather than concerned it may be a symptom of something sinister, he worries about how he can disguise it as he embarks on an important first date: “…because the growth was flatish, it lay along his palm like one of those fortune telling fish you get from Christmas crackers. It didn’t stick out an at angle or anything.”

The majority of stories in this collection involve couples, often unnamed and of indeterminate age and gender – which may be intended as a reflection of our anxieties about gender identity and politics – but which often gets in the way of the story. Who are these people? I found myself asking, flicking back over pages to check I hadn’t missed something. Many of the stories employ the second-person epistolary narrative: “‘Front, middle or back,’ I asked and you pointed to the front row where there was room at the edge of the bench. We took our places and you munched on the almonds.” This device often works in fiction to create a sense of voyeurism or proximity, yet in these stories it has the curious effect of creating a glassy distance between text and reader, and this is the problem. Even when characters are named or appear in third person, they are etched lightly. In “Beaujolais Day”, we learn that Nick has been with Debbie for a year, has bought an old chapel, earns enough money to eat at a good French restaurant, and knows his Bordeaux from his Beaujolais, but when he’s confronted by a waiter who once bullied him at school, and takes his revenge, instead of rooting for him we feel so little that we barely care.

North is an excellent social observer. She ably chronicles a country full of curiosities, ambiguities and hypocrisies, from our preoccupation with house ownership, cut-price travel and road rage, to a land of CCTV, polytunnels, and department stores closing down. She has a keen ear for dialogue, as the opening lines of Punch brutally demonstrate: “Fat fucking cow. Fat fucking dyke. Your brother’s a spaz,” and is gifted with a poet’s eye when it comes to detail: “The rain sounds like someone drumming their fingers softly against a coffee table.”

There are many flashes of original, incisive writing (“Black & White Buttons”, “The Largest Bull in Europe”) in this collection, yet too many of these stories left me with a feeling of: “So what?” It may be fair to say that slice-of-life stories do not turn on a plot, conflict or exposition, but then they must elevate or illuminate the everyday to something startling and revelatory; to haunt and unsettle. In this collection North has created incisively told anecdotes filled with a sense of anticipation, of something struggling to rise to the surface – yet it rarely does, leaving the reader instead with a sense of frustration, of a blow one’s been waiting for which lands wide of the mark.

Punch is published by Cinnamon Press.

About Christina Sanders

Chris Sanders has been writing short stories for over ten years. She has been published in: Writing Women, Quality Women’s Fiction, Peninsular and TQF. In 2011 she won an Arts Council bursary to appraise her first novel, and has contributed to various Arts Council writing projects. At present she is working to complete a collection of short stories on the theme of ‘Compromise.’ Chris Sanders holds a Masters in Education, and is currently working with women from BME communities in Hastings to use storytelling as a way to explore identity and heritage.