You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingRead Litro’s interview with Guillermo Stitch.

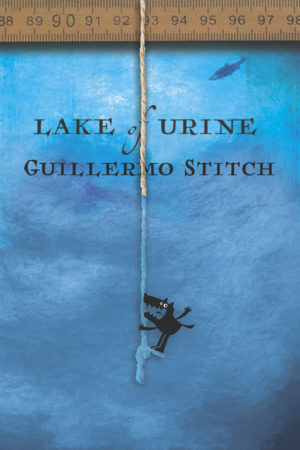

Lake of Urine is original and absorbing, a mad whirly-gig romp through the lives of the Wakeling family. A post-modern fairy tale told in the absurdist tradition. There is a house in the woods, a heroine, an anti-heroine, a madman, a witch, a magical lake and a house brimming with secrets. It is daring, exuberant, stuffed with satire and literary tropes from Dickens to Barthelme, Calvino to Angela Carter, and totally exhausting.

Subtitled “a love story”, the novel is set in an ambiguous American outback, in an era where smock-wearing peasants drive horse and carts as well as cars, talk on mobiles and live in proximity to multinational corporations. What passes for “love” is unclear. The long list of encounters which comprise a large part of the novel are brutish, debauched, and devoid of any intimacy. Romance is as sparse as the string which holds the story together.

The novel follows the story of The Wakeling family, who live in “the compound” on Swan Hill. It begins in the snowy chill of winter with Seiler, the family factotum, who recounts his unrequited love for Emma Wakeling’s daughter Noranbole, and his intense dislike of her sister Urine, before embarking on his misguided vanity project to measure the depth of Swan Hill lake with a length of string; the consequences of which are both fantastic and surreal.

The second part of the novel is given over to Noranbole’s escape from the backwoods to the Big City with her fiancé Bernard. It’s a savagely satirical commentary on capitalism, consumerism, vacuous celebrity, and corporate America, where Bernard’s incomprehensible utterances (in Spanish, hybrid European, Asian and binary code) appear cogent in the land of corporate strategy, think tanks, and management speak; where conglomerates talk of radical rethinks and hammer out exponential crisis in unchartered waters. Language is nonsensical, reduced to a post-modern Mall of Babel. The more they speak, the less they say.

In the third, and most conventional part of the novel, Emma Wakeling tells the story of her eight husbands. Each husband, if not downright brutish, has more than their fair share of perversities and infidelities in these tales of Gothic backwoods courtships. Told with wit and economy, the story of Emma’s desultory marriages is deftly woven between descriptions of the rooms of the Wakeling house, all of which bear witness to private perversions, secrets, and misdeeds, recounting the story of Emma’s conception, birth, her courtships and why things in the attic go clunk.

The final part of the book returns to Swan Hill sometime hence. Spring blossoms but things are getting ugly. New etiquette and laws are needed. The overreaching arm of the state is omnipresent as Seiler revisits the scene of the crime in one last bid to measure the depth of the lake. Mysteries are solved, the jigsaw slots neatly together in true fairy-tale tradition. Magic abounds. Urine reappears. Noranbole escapes, and Seiler gets his comeuppance.

In an interview with Litro, Stitch claims Lake of Urine should not be considered as a cultural critique. He rejects the absurdist tag, preferring the term fabulism, invoking the ghosts of Aesop and Calvino. While the novel clearly contains elements of metafiction, hybridity, fantasy wrapped up in a convincing real-world setting, it lacks the depths associated with these works. Stitch is at his best subverting rather than narrating. Despite his reticence to be thought of as cultural critique, it is the dazzling pyrotechnics of language and satire that bind the book together; the quest for meaning in world which clearly has none. The characters are tissue thin, the plot lurches like a dodgem in spastic motion, in stops and starts, yet none of this seems to matter. For sheer exuberance and energy alone, the journey’s worth taking. No one emerges from the Wakeling compound unscathed.

Lake of Urine is published by Sagging Meniscus.

About Christina Sanders

Chris Sanders has been writing short stories for over ten years. She has been published in: Writing Women, Quality Women’s Fiction, Peninsular and TQF. In 2011 she won an Arts Council bursary to appraise her first novel, and has contributed to various Arts Council writing projects. At present she is working to complete a collection of short stories on the theme of ‘Compromise.’ Chris Sanders holds a Masters in Education, and is currently working with women from BME communities in Hastings to use storytelling as a way to explore identity and heritage.