You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Towards the end of the tortuous, sixty-page Proustian party scene that ends Virginia Woolf’s The Years, WWI veteran and man-of-the-world North surveys the revellers and observes, ‘they were all the same sort. Public school and university . . . Where are the Sweeps and Sewer-men, the Seamstresses and the Stevedores?’ It’s a question one could ask of much contemporary fiction, though not of these two debut novels, in which working-class culture, and the marginalised, including the disabled, feature prominently. In Kit De Waal’s My Name is Leon, a nine-year-old mixed-race boy enters the care system and looks on helplessly as his half-brother is taken away for adoption; while in Emma Claire Sweeney’s Owl Song at Dawn, the septuagenarian proprietor of a seaside guesthouse is visited by an unwelcome figure from her past, the last person alive to have known her severely disabled sister. Both books are unafraid of cultural taboos, and of exploring uncomfortable or challenging subject matter. Both are timely, too. It’s significant that a lack of diversity is also something that’s currently being campaigned against within the British publishing industry.

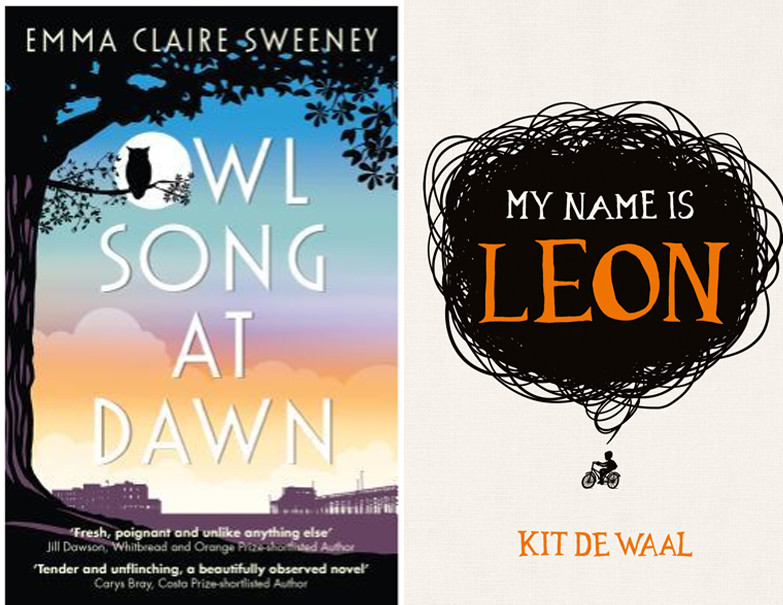

Towards the end of the tortuous, sixty-page Proustian party scene that ends Virginia Woolf’s The Years, WWI veteran and man-of-the-world North surveys the revellers and observes, ‘they were all the same sort. Public school and university . . . Where are the Sweeps and Sewer-men, the Seamstresses and the Stevedores?’ It’s a question one could ask of much contemporary fiction, though not of these two debut novels, in which working-class culture, and the marginalised, including the disabled, feature prominently. In Kit De Waal’s My Name is Leon, a nine-year-old mixed-race boy enters the care system and looks on helplessly as his half-brother is taken away for adoption; while in Emma Claire Sweeney’s Owl Song at Dawn, the septuagenarian proprietor of a seaside guesthouse is visited by an unwelcome figure from her past, the last person alive to have known her severely disabled sister. Both books are unafraid of cultural taboos, and of exploring uncomfortable or challenging subject matter. Both are timely, too. It’s significant that a lack of diversity is also something that’s currently being campaigned against within the British publishing industry.

Set in the early years of the 1980s, My Name is Leon reaches its climax as the Brixton riots rage, and the opulent Royal Wedding goes ahead oblivious to the social upheaval in Thatcher’s rotten Britain. This juxtaposition gives the reader an idea of the book’s political engagement, though for most of the novel this is a quiet underpinning that doesn’t draw attention to itself. The emotional core of the book is the eight-year-old Leon’s journey through a series of separations, and his search for his white half-brother, Jake. First, his alcoholic Caribbean father, Byron, disappears. Then his mother suffers a breakdown after Jake’s white father, Tony, abandons her, forcing Leon to be placed into care with Maureen, a homely veteran foster mother. Finally, and most wrenchingly, the ‘noticeably different’ Jake is taken away for adoption, a scene handled with such sensitivity and honesty that it’s hard to imagine it done better: As the social worker argues her case, Jake is torn: ‘Something inside him is telling him to run away or to hit the lady’. Here de Waal is at her most convincing, describing the roots of lifelong male anger. Past stress equals present weakness; past abandonment, present violence. The emotions invoked by sibling separations and the care system are perfectly conveyed. Instead of internalising the primal moment of abandonment, Leon’s first instinct is to binge eat and then trash his room. De Waal also expertly catches the child’s-eye-view of the world – one that is endlessly questioning and robust, yet also intensely vulnerable. For once the ubiquitous present tense of much modern fiction is justified: the drama of childhood all happens in the here and now. Leon has no guarantee he will ever see his brother again, and this fear is all-consuming for much of the book. His life is full of instability, uncertainty, and jargon he doesn’t understand (such as ‘halfway house’), also the phoney ‘pretend smiles’ of teachers and social workers.

When Maureen’s ill health forces yet another separation on Leon, he finds himself in a multi-racial neighbourhood for the first time, and begins to feel a sense of cultural recognition. Here he is drawn to Tufty, an ironically named bald black cyclist, and an incongruous figure of adult male responsibility and sanity; both qualities absent from his life thus far. Even more incongruously, the action switches to an allotment overlooking the town, where Leon is exposed to the very creepy Mr Devlin – ‘a dark blanket of sourness’, and an alcoholic keeper of knives, guns and strange carvings – and Castro, a sacrificial lamb who is later beaten to death in police custody. For the first time, Leon sees Black Power posters, suggesting a racial solidarity he hadn’t previously imagined. The notion that consanguinity can provide a substitute family is fully explored, especially in the touching scene where Tufty introduces Leon to the music of King Tubby, Bob Marley and Burning Spear. As the wider world intrudes in the shape of ’81 riots, brutally juxtaposed with the profligate Royal wedding, the prose achieves a gritty lyricism: ‘An angry ghost of black smoke rolls up the street . . . a car lying on its side’. Yet even here, De Waal refuses to provide easy solutions to age-old conflicts. When Irish Devlin and Tufty fight, they fail to see each other’s struggle against colonial oppression, just their own particular plights.

Skilfully plotted and executed, My Name is Leon handles difficult dramatic scenes with great dexterity. The exchanges between Leon’s de facto father, Tufty, and the police have real bite, just when one feels the novel might be leaning towards sentiment. Full of warmth and humanity, and rich human insight, the book generates questions long after it has been finished, even more so at a time when racism and class are at the top of the British political agenda. Seen in this light, even the allotments don’t seem so incongruous. The traditional escape for the working-class father, here Leon gets to plant his own Scarlet Emperor, a perfect metaphor for growth and new life, and of starting again in new soil.

Emma Claire Sweeney’s Owl Song at Dawn also focuses on a location that still provides a safe haven for the widowed or divorced working-class male: the seaside guesthouse. The Sea View Lodge in Morecombe, run by Maeve Maloney, is unique in that over the years it has specialised in a disabled clientele: ‘We used to take all sorts: The Deaf Choir of Greater Manchester, a wheelchair basketball team, paraplegic windsurfers’. They also have, in the figure of Steph, a receptionist with Downs syndrome.

Having grown up with Edie, a twin sister with severe learning disabilities, Maeve feels duty bound to redress the balance of able-bodied staff to disabled in her establishment. This is not surprising, given how her twin was once treated. Ranging back widely through the previous century, and into Maeve’s deep past, we follow Edie’s journey from parental care to hospitalisation (after a grand mal seizure), to the Nazareth Convent Home. These flashbacks deliver the most moving sections in the book, giving us a different Maeve to the rather severe pensioner we meet at the start, and provide an insight into how the disabled were once stigmatised and treated. Edie’s family are immediately advised to institutionalise her, and ‘focus your love on your normal child’. Indeed, notions of normality are explored through a series of letters from doctors that refer to Edie as ‘your afflicted daughter’, ‘your unfortunate daughter’, and your ‘mentally subnormal’ child. This is offset by Edie’s progress in other, less conventional areas. She becomes the ‘finest singer in the choir’, and delights Maeve with her cascade of free-association speech. The sensitivity with which Edie is portrayed recalls Bellow’s depiction of the disabled Georgie in The Adventures of Augie March. Sweeney cleverly employs the device of addressing the sister in the intimate second-person as ‘you’, bringing the reader closer to the experience of growing up with a sister with severe learning disabilities. Maeve also experiences much survivor guilt, stemming from the notion that she might have ‘deprived you of nutrients or damaged you in the womb’, and the fact that she left the room just before Edie’s life-changing seizure, which left her twin in a ‘vegetal state’.

Against this action set in the distant 40s and 50s is Maeve’s troubled relationship with Vince Roper, who turns up unannounced at Sea View Lodge. Vince was pivotal in her life once, and Maeve also ‘held him responsible’ for Edie’s fate, though the reasons for this are opaque, and take a while to surface. As a plot motor, however, it holds the book together perfectly, as does a secondary story involving the love affair between Steph and her disabled friend, Lou, which goes some way to breaking the taboo surrounding such unions (in the 40s, the book tells us, they would both have been sterilised).

Poignant and rich, and British as a stick of Morecombe rock, Owl Song at Dawn provides an insight into the hitherto hidden world of the severely disabled, and families who vehemently oppose their institutionalisation. Here, they become people with voices, not just statistics. As with Georgie’s forlorn moan in The Adventures of Augie March, (through which Augie’s disabled brother ‘deals with his soul’), the decision to convey Edie’s exultant, exuberant, nonsensical language gives her back her proper humanity.

About Jude Cook

Jude Cook lives in London and studied English literature at UCL. His first novel, BYRON EASY, was published by William Heinemann of Random House in February of 2013. He has written for the Guardian, the Spectator, Literary Review and the TLS. His essays and short fiction have appeared in Litro, Structo, Long Story Short and Staple magazine.

I was thus engaged, lying on top as in an old-fashioned married couple, male over female, when I opened my eyes and met hers, willing, wide and moist. That’s when I remembered the plan, no longer a plan so much as an arcane summons from the beyond. It’s a game, I informed her as I pulled the pillow from under her head and crushed it on her face. The movement was as smooth as the slide of the spade from between the bags of sand and quicklime the first time I killed Guillermo.

https://euro-to-usd.com/