You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

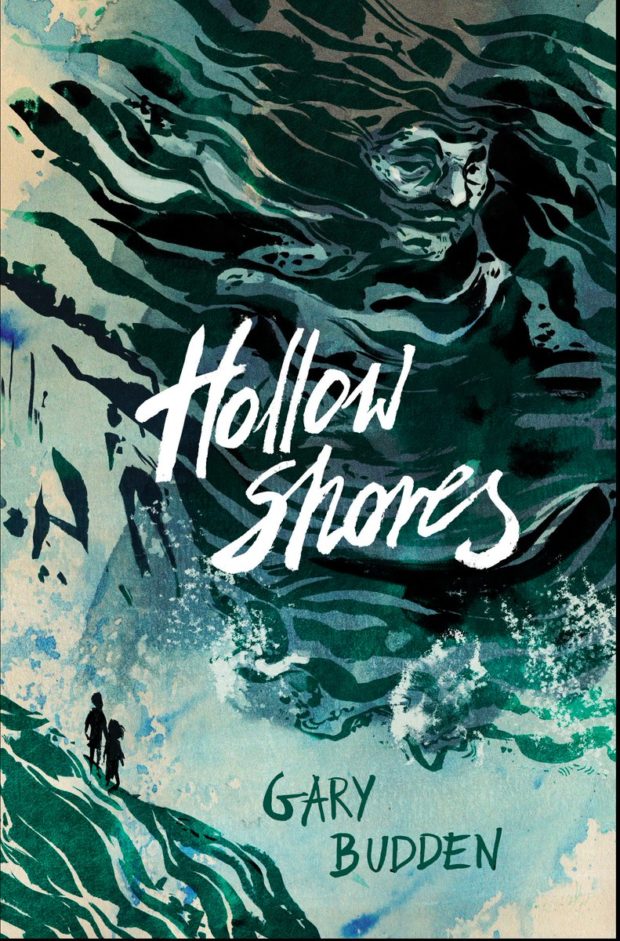

Go shoppingI first came across Budden’s writing in Unthology 7, which came out in 2015. His contribution “The Hollow Shore” struck me as the best in the anthology, and one of the best I had read in years – as I noted in a blog post at the time. News of his debut collection Hollow Shores reached me several weeks after publication in October of last year.

The Unthology 7 story fittingly lends its name to the collection as a whole. You might read reams of critical essays about the loss of England’s heritage, how retail chains have levelled towns to a single non-contiguous ahistorical space, but in this story the eeriness and sense of loss is rendered palpable. Simon has made a mess of his life, can no longer afford London rents, and moves back in with his parents in the coastal town where he grew up. The parents are genuinely happy to see their son, and on the following Sunday they drive out to a gastropub for dinner. Simon asks his father why they had chosen a chain pub instead of some lovely old place in the real town centre. “My father looked up from his paper. ‘We like it here.’ For the first time that day, he smiled.”

It’s a moment of Stepford-Wives unease, a glimpse below the surface. Simon then organises a day-long hike with an old friend. They are to walk along the Hollow Shore – a historic route on the marshy coast. The landscape seems remote and misty, yet the housing sprawl of southeast England is never far distant. At one point the pair of ramblers spot an interesting amalgam of rusted machinery embedded in the marsh. “Something they used when people still worked for a living!” one of the walkers says sourly. It’s the type of sharp insight which is dotted through the collection: the characters are aware of the loss of old virtues, a fear of living in a “brandscape that was shutting down any possibility”. The atmosphere of eeriness and repressed histories coalesces towards the end. The story is a highly effective Brexit-England portrait, but a lot more besides.

All the stories are of our era, this decade – social media, Amazon, portfolio purchase of residential apartments, extortionate rents, franchise coffee outlets, Sports Direct, Saint George’s Cross flags, parakeets in London skies. The merely human has come to seem out of place. Budden’s protagonists are generally in their forties, and share a history of punk gigs, protests, and drug-charged conversations. “Punk to me meant at least some kind of ideology, a belief in something, not this creeping nihilism” laments one character. Now they find themselves driven by different needs – a need to feel rooted in a landscape, to forge a connection with nature. There is a sense of mapping out and rendering to human scale the surrounding landscape of franchise outlets, motorways and retail parks, and feeling a reciprocal affinity with the wildlife that has colonised such an environment.

Ancient sensibilities are at work here – love of a home landscape, a need to connect with folklore. Use these themes in a novel set in the West of Ireland, and your readers will settle the cushions for a comfortable read. But even as a politically unsophisticated reader, I sensed that it was a different matter to have such sentiments in fiction set in towns where the Saint George’s Cross is frequently seen hanging from bedroom windows. Rather naively, I wondered if other readers might be aware of this – but of course they were.

“I find myself in a difficult position. I consider myself to be an anti-fascist, and yet I read many, many books concerning the British landscape – and I’m aware of how these feelings I hold towards landscape dovetail with those I disagree with, and at times despise.” – Budden in interview in The Quietus, October 24, 2017.

“Landscape punk” is how Budden describes his writing. Psychogeography is another applicable word: it means the exploration of environment in a creative and idiosyncratic way. “He just feels the compulsion these days to connect town to town by foot – no car, bike or train providing enough significance.” Or in another story: “I enjoy the names of herbs and wildflowers that grow on the unloved railway embankments, a different lexicon for understanding the city.”

In novels of this post-truth, almost post-human age, it is common to find techniques such as surrealism or absurdity used to convey the experience of disorientation. To these affects, Budden throws in horror. Horror in existential and spiritual form, and also good old-fashioned gothic. This use of horror elements against a bland urban setting delivers quite a shock. One can’t help but read a certain message into all this: the wraiths and white foxes and straw revenants, which we had thought we had consigned to the past, will return to haunt us. And so too with political sentiments we had thought the world had outgrown.

Several of the stories are concise “concept” pieces. In “Baleen” the corpse of a whale is washed up on an English beach. Soon it has its own Twitter account to document the process of decay. This set piece is strongly reminiscent of Ballard. “Platforms” is an eyes-wide-open travelogue of a commuter’s daily route. This is not passive perception: it’s seeing things in the intense and erratic light of the imagination. It will hopefully prompt the reader to attempt a similar exercise of expanded awareness on the morning commute. “We Are Nothing but Reeds” is a powerfully simple story of a couple beaten down by the daily routine in London. “Life reduces itself.” They escape for a weekend to a small village on the Norfolk coast. That’s it, that’s the whole plot, but in Budden’s hands it is a reminder of how deep the craving for the redemptive power of nature can be.

This is not just a brilliantly written collection; it is written with passion and anger and hope. It’s a common term of praise to say that a piece of fiction raises many questions. Budden’s work doesn’t just raise questions; it warns of the dire consequences of neglecting the human need for a connection with nature, and points the way towards a love of one’s home landscape and folklore which is free of dubious political connotations.

Hollow Shores is published by Dead Ink Books.

About Aiden O'Reilly

I am originally from Dublin, and graduated in mathematics. I abandoned a PhD in complex dynamical systems. Later I lived 9 years abroad, in London, then Berlin, and later in Poland. I have worked at many different jobs to earn money. My short fiction has appeared in Prairie Schooner, the Dublin Review, the Stinging Fly, the Irish Times, and many anthologies and literary magazines – a total of 29 stories. I review books for the Irish Times, the Dublin Review of Books and other places.