You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

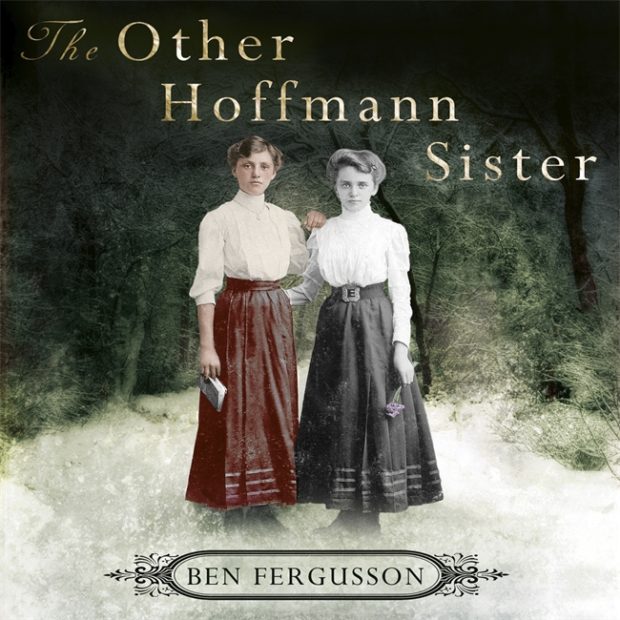

Go shopping The past few years have seen, once again, a growth and movement behind nationalism. From the cries to ‘take back our country’, the rejection of globalism for protectionism, to Brexit and Trump, which have given renewed vigour to prejudice and hate crimes, we are facing a period in history that is beginning to reflect the ideologies and desires of the early twentieth century. That was a time when colonisation was considered normal, a sense of pride was born from expanding empires, when minorities were second-class citizens, illegal or racially profiled in a much more virile, legal and widespread way than today. The Other Hoffman Sister (Little, Brown), Ben Fergusson’s sophomore historical fiction novel, straddles both the apex and nadir of imperialism, nationalism and when European countries had divided the globe into their own territories. Spanning pre- and post-World War One Germany, Fergusson’s novel is timely, coming when the setting of his tale and our own contemporary landscape are growing all too similar.

The past few years have seen, once again, a growth and movement behind nationalism. From the cries to ‘take back our country’, the rejection of globalism for protectionism, to Brexit and Trump, which have given renewed vigour to prejudice and hate crimes, we are facing a period in history that is beginning to reflect the ideologies and desires of the early twentieth century. That was a time when colonisation was considered normal, a sense of pride was born from expanding empires, when minorities were second-class citizens, illegal or racially profiled in a much more virile, legal and widespread way than today. The Other Hoffman Sister (Little, Brown), Ben Fergusson’s sophomore historical fiction novel, straddles both the apex and nadir of imperialism, nationalism and when European countries had divided the globe into their own territories. Spanning pre- and post-World War One Germany, Fergusson’s novel is timely, coming when the setting of his tale and our own contemporary landscape are growing all too similar.

The novel begins in German South West Africa, a colony from 1884 to 1915, introducing two families: the aristocratic Von Ketz family, and the aspirational Hoffmanns. The Hoffmans had relocated to the colony in 1902 where they bought a farm from the Von Ketz family. Set in the blistering heat and arid African landscape, the first part of this novel centres on the titular sisters, Margarete and Ingrid, in their adolescence. The sisters are polar opposites: Ingrid is studious, inquisitive and steady, whereas Margarete is unsettled, flighty to the point of petulance. Perhaps the latter is Fergusson’s way of highlighting the aloofness and snobbery of the middling-upper-class Europeans. The thread of this section of the novel is split in three: Ingrid’s infatuation with their servant, Hans, and her growing love of poetry and languages; Margarete’s ever-impending betrothal to the Von Ketz’s son, Emil; and the twining of the two families in politics, ambition and money. The climax of this part of the book centres on the Herero uprising in 1904, which forces the families to flee back to Germany, with some unexpected losses as a result.

The setting of German South West Africa, now Namibia, provides one of the most interesting aspects of the book. Fergusson uses the bareness, the barren and stifling location of the farm to reflect the simmering tensions between the locals and the German colonisers, as well to highlight the two German families’ unsuitability for their new environment. It also, importantly, served as a point of education – for me, at least. While fairly well read on the colonisation of Africa, predominantly focused on the British, Portuguese and French occupancy, my knowledge of German colonies was very little. It is important that this part of history is both taught and engaged with more by schools and the media. Fergusson in this novel unveils some of the atrocities and horrific racism that occurred in the colony, as well as emphasising the ignorance, haughtiness and amorality of European thinking and ideals.

Back in Germany, the drive of the narrative is towards the impending wedding of Emil and Margarete, as well as the latter’s apparently failing mental health and the concern this creates on both sides. Surprisingly, one of the most touching moments of the entire book is a conversation between Ingrid and Emil about their shared sense of dislocation, their loneliness and inability to feel at home after their childhoods spent moving around, a sentiment any expat child, or adult, can relate to.

Disaster strikes on the night of the wedding when Margarete disappears. Due to her previous mental health issues, she’s assumed to have committed suicide in the nearby lake. Ingrid though is unsure whether her sister really has taken her own life, or run away. Intersected by the First World War, the rest of the novel is dedicated to Ingrid’s work as a translator; one of the more interesting parts of the novel, her engagement with left-wing politics; and her search for what truly happened to her sister on that fateful wedding night.

The premise of this novel sounded fascinating, and given the awards won by Fergusson’s debut, The Spring of Kasper Meier, I had high expectations for a book that examined and exposed a period in history that was fraught with racism and discrimination, along with offering an intriguing mystery. However, for this reader at least, this novel lacks numerous fundamental components that would have made it a more succinct and accomplished piece of literature.

The Other Hoffmann Sister touches on many important periods in history, which have had devastating effects on society, culture and the people who lived through them. From the First World War, to the German colonies in Africa, the Herero uprising and genocide, through to the crippling effects that reparations and the Treaty of Versailles had on Germany. It lays the foundations for a book full of turmoil, change and tension, but falls short of using them to create a novel that could have been simmering with explosive charge at every turn. Perhaps the biggest disappointment is the lack of actual engagement with and exploration of the historical, and the impact such events could have had on the characters and plot.

The novel frequently, and frustratingly, jumps between time, place and historical event. Dropping in and out of moments, scenes and periods can be an effective plot device, but it’s one that doesn’t work here. The Hoffmann and von Ketz families flee the uprising in South West Africa, but the reader does not see these events – we are not given any in-depth background and context to the uprising or the political situation that gave rise to it, nor do the characters stay long enough for the uprising to cause development or change in them. The First World War is completely skipped, and while there are the occasional scenes of demobbed men and the rationing of food, this hugely important moment in history is avoided.

Ingrid and her friend Hannah meet with socialist revolutionaries in what’s described as a ‘remarkable meeting’. In fact, the only thing discussed between the two characters and Rosa Luxemburg, the Marxist theorist, philosopher and activist, is a bird singing above them. Rather than using this moment between two women interested in the new socialist movement in post-war Germany, in which Luxemburg could have been a tremendous influence on them, a meeting of three women dedicated to breaking the shackles of an unfair society, Fergusson, as in the case too often in the novel, wastes what could have been a significant influence on character and plot development. Why include this meeting, or even the socialist revolution, if it does nothing to further character or drive the narrative?

We are told of horrors, how it affected the characters so badly, but we are never shown it. Doing so would have helped draw out key themes more, as well as creating more three-dimensional and distinct characters, whereas unfortunately the lasting image is of countless scenes of choking back sobs, bursting into tears or throwing tantrums. There are a multitude of ways of engaging with pubescence, mental health or female characters and it was disappointing and uncomfortable that Ingrid and Margarete seemed to be based on stereotyped behaviour or gender. While Fergusson may have been trying to exhibit a sense of entitlement and being spoiled it, made them at the least unlikeable. With this presentation, it was difficult to sustain an interest in either sister. If Fergusson had engaged more with the important historical events, placing the women in the centre of the action rather than skipping past it, he could have utilised this to have meaningful nuances and effect on both women.

The denouement of Ingrid finally discovering the fate of her sister is rushed. The details are revealed over a brief conversation at a table, and hold little emotional impact either on the character or the reader. Partly because Margarete is thoroughly unpleasant, it’s difficult to care why she disappeared. Throughout, there is insufficient engagement with her disappearance, lack of the plot construction that would make for a page-turning mystery, or any urgency to solve the mystery. Even a reader who doesn’t wish for a heavy read that grapples with the social, cultural or political too much would miss the essentials of a compelling mystery, the building and sustaining of suspense to keep a reader interested and invested in the story.

There is great promise with this book, excellent ideas and themes. I feel like with greater focus on plot, and the cutting out of quite a few scenes and locations, then the characters and mystery could have flourished more. Fergusson touches on important themes in this novel, from racism and colonisation to the repercussions and corruption of greed, ambition and power. He explores a period of history that needs to be discussed, actions and events that need to be addressed, as well as reinforcing our need to learn from those mistakes and ensure they are not repeated.

The Other Hoffman Sister is published by Little, Brown.

About Michael Handrick

Michael Handrick was born in the UK and raised in various countries. A graduate from the Creative and Life Writing MA at Goldsmiths, University of London, his short stories have been published in various anthologies; his journalism appears in magazines such as PYLOT, as well as academic research published by The Inter-Disciplinary Press.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (also known as Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi) is a 2017 American epic space opera film written and directed by Rian Johnson.