You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

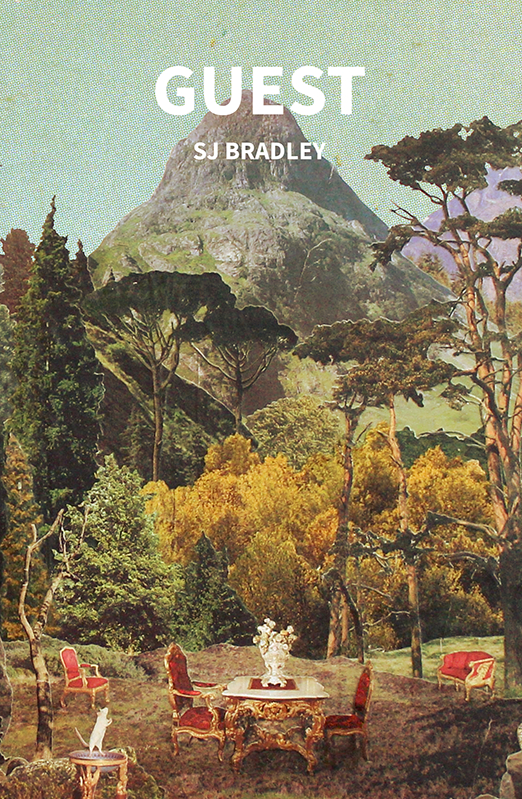

Go shopping Small publisher, Dead Ink has a mission “to bring the most challenging and experimental new writing out from the underground”, and they have certainly achieved that by publishing SJ Bradley’s second novel, Guest.

Small publisher, Dead Ink has a mission “to bring the most challenging and experimental new writing out from the underground”, and they have certainly achieved that by publishing SJ Bradley’s second novel, Guest.

For a start, the book tackles one of the most scandalous abuses of our democracy in recent history – the infiltration of the Green movement by undercover policemen who formed relationships and had families with activist women. The truth about the National Public Order Intelligence Unit came to light in January 2011, when PC Mark Kennedy resigned from the Metropolitan Police, making headlines and expressing remorse for his role monitoring “domestic extremists”.

Since then, apart from occasional news stories – and the ongoing pain of women who were deceived by these men, shared their lives and love with them, and in some cases had their children – this topic has been pretty much neglected by the mainstream media, especially in literature and drama.

This is where I have to declare an interest: I was a squatter activist in the 1990s, which is why – when the opportunity came up – I was so keen to review Guest. This does mean, however, that I couldn’t help compare the story to my experience of squatting and the Green movement, and have possibly reviewed Guest a little harshly as a result.

The book tells the story of Samhain – a young squatter living in an abandoned hotel somewhere in the North of England. The exact setting is never quite stated, but it feels like Yorkshire. Early on, Bradley brilliantly sums up the whole of ethos of squatting:

“Discarded things from which they made a life. Samhain had no money, and lived like a prince. He didn’t have to work. Other people wasted hours of their lives in jobs they hated, or got into massive debt buying things they didn’t need. Not Samhain. He was free. Living behind found fabric, in a subterranean womb of deep, mossy green. This was the place where Samhain really belonged.”

There are some inaccuracies about the details of squatting. (Three people living in a massive hotel without inviting others to join them, for one thing. You wouldn’t want to leave your squat empty – someone has to be in all the time – and on the squatting scene you always know other people who need somewhere to live.) But perhaps I’m being picky. And I digress.

Having said that, the facts about the National Public Order Intelligence Unit appear very natural and smooth – seamlessly integrated as part of the story without interrupting the flow or screaming “Research! Research! Research! I’ve done my research!” at the reader.

Samhain learns that his father, a man he never knew, was an undercover cop infiltrating the Green movement. Around the same time, he discovers that his ex-girlfriend has had a baby, all his so-called mates have been keeping this from him and he now has to face up to being a father.

Bradley lets the confusion and anger that Samhain experiences build into an inner turmoil which she depicts beautifully. At this point in the story, Guest achieves an unputdownable quality, but the tension is interrupted when Samhain avoids his responsibilities by going off to Europe to play with his band.

The series of vignettes that follow distract from the main story. Perhaps it mirrors the way Samhain chooses distraction to escape from his newly-discovered paternal responsibilities, but for me the crux of the story is lost. The vignettes, the European tour – it all seems irrelevant.

As I read, I wanted desperately to get back to the main action and the squatting activist scene in Yorkshire. I yearned for a deeper sense of what it must be like to be one of those children – like Samhain – who was born out of a state-sponsored lie. It would have been an incredible achievement if Bradley had stuck with the protagonist’s main problem and explored it more deeply.

That said, Bradley’s prose is often vital, painting delicate images, whether it’s the squat scene in England:

“A dead house spider, legs curled inwards in death, crumbling in the cup.”

…or on the Continent:

“There were two dogs, whip-tailed and dark with fur that looked like something from a shoe brush.”

Samhain’s tiredness is “marrow-deep”, lying “in his veins moving sluggishly along”.

A lot of the dialogue between the characters is light and funny, and the settings are visual and interesting. (It would make great television.) But while the characters are good at banter, they often seem only to function as sounding boards for Samhain’s problems.

The women in Guest are either sweet or sour – with the heroine, Mart, dependable and strong – while the men are reckless, tribal, self-indulgent and largely useless. “A woman keeps you in line!” says one of the characters (male) later in the book. I found this gender stereotyping surprising – as well as disappointing – in a book that highlights one of the greatest acts of (state-sponsored) misogyny in recent history.

Guest is a light read but it tackles a very important and difficult subject. It is sympathetic to a section of society that is all too often maligned in the tabloid press. Most importantly, it highlights a huge wrong, whose victims are still campaigning for justice. Guest is a brave book. Bradley should be congratulated for creating it and Dead Ink applauded for supporting it.

Guest is published by Dead Ink Books.

About Juno Baker

Juno Baker is a freelance writer, and editor of the University of Cambridge's Leading Change website. She has written articles for the Guardian and once interviewed Dolly Parton. Her fiction has been placed in several competitions – including Winchester Writers Festival, Pindrop, Short Fiction and Rubery – and was recently shortlisted for the VS Pritchett Short Story Prize. Her stories have also appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, most recently, Mslexia, Unthology and Litro.

- Web |

- More Posts(13)