You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

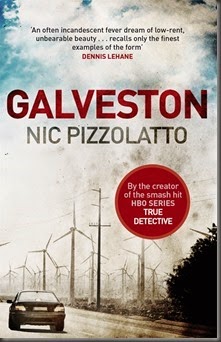

Go shopping This weekend saw the end of True Detective’s UK run. For those of you already missing its blend of gothic horror, taut characterisation and wire-sharp storytelling, the show’s writer Nic Pizzolatto’s novel Galveston may help fill the void.

This weekend saw the end of True Detective’s UK run. For those of you already missing its blend of gothic horror, taut characterisation and wire-sharp storytelling, the show’s writer Nic Pizzolatto’s novel Galveston may help fill the void.

Told from the perspective of a sardonic, haunted, alcoholic lone-wolf (sound familiar?) the novel switches back and forth between a botched assassination attempt in 1987 and the lead-up to 2008’s Hurricane Ike. Published in 2010, Galveston’s themes throb through the later HBO series. They share a visual landscape – Pizzolatto’s native Louisiana skyline frosted with stars, lukewarm beer pitchers, the looming threat of Angola prison, hookers with eyes “like a saint’s” and so much J&B you wonder how anybody gets anything done. But each of these images carries a symbolic undertow and point to something larger and more rotten in the human condition. From reading Galveston, it is clear that themes of addiction, cruelty, evil, redemption and pervasive violence towards women have preoccupied Pizzolatto for some time.

For anyone already missing Matthew McConaughey’s masterfully rendered Rust Cohle, reading Galveston will feel like calling up an ex-lover just to listen to their answerphone recording. That voice – wry, incisive, brutally human – was clearly born in these pages. “The past isn’t real,” Roy tells Rocky. “Tell yourself that. The past isn’t real. It’s just one of those ideas you get that you think is real.” This concept reveals itself throughout True Detective, most notably in Rust’s speech on locked rooms in episode three – “It was all the same thing. It was all the same dream […] A dream about being a person.” The similarities are almost too numerous to mention: in the first chapter, you can almost see McConaughey deadpanning Roy’s admission that he’d “tried to conceive of not existing, but… didn’t have the imagination for it.” A depiction of seagulls walking with “a kind of haughty entitlement that made me think of clergy,” evokes Rust’s hatred of Evangelical bullshit merchants. But Roy and Rust also overlap in moments of lucidity and resignation: “the past clots like a cataract or a scar, a scab or memory over your eyes,” says Roy. “And one day the light breaks through.” For those of us with the final episode’s coda still ringing in our ears, this proclamation will sound satisfyingly familiar.

The buds of other True Detective characters also sprout up here: Rocky – the doe-eyed hooker who reminds the aging Roy of his own vitality – is imported almost wholesale into Marty’s dalliance with a former child prostitute in Episode 6. As Roy admits blithely, “sex with a young woman implied a measure of immortality to me.” Similarly, Roy’s abortive reconciliation with his ex-lover – “a white blouse poured down her like cream. A string of pearls and a large ring in addition to her wedding band and diamond” – reverberates through Marty’s trip to see Maggie, remarried and living in lavish, beige happiness without him.

Herein lies the pleasure of Galveston for a True Detective addict – in these moments it’s almost as if Pizzolatto has pressed pause on the series and dipped into the character’s minds. As thrilling as it was, True Detective often barrelled through plot points – paedophile rings, prostitution, multiple murder investigations, pagan ritualism, religious zealotry, marital betrayals and dissolving family ties were all ticked off over the course of a packed eight hours. Pizzolatto whittles the novel’s storyline to a dagger’s point. By allowing Roy this time and space to reflect, Pizzolatto is able to pin down and dissect the nihilist and existential tenets people have praised so much in True Detective. This is not to imply that Pizzolatto forces philosophy down our throats: he handles these complex concepts masterfully, using gesture and economy to tell his story with a grace to which all True Detective fans will be accustomed.

And it is grace that elevates both True Detective and Galveston above the muddy backwaters of straightforward genre. Both works are noirs backlit by empathy, crime fictions humming with moral ambiguity, luminous Southern gothics shot through with realism. While waiting for Season Two to hit our screens, bereft True Detective fans ought to give Galveston a read and take comfort in the fact that, whatever happens, the show is safe in the hands of a truly original and gifted writer.

Galveston is available now. Buy it from Foyles.

About Maia Jenkins

Maia is a London based writer. She grew up in Singapore and France but moved back to the UK in 2009. She has just completed an MA in Modern Literature at University College London and is now working on a novel. She also holds a BA from King’s College London, where she was a founding member of the literary society journal ‘Of Cabbages and King’s’. While at university she received the Henry Neville Gladstone prize and the Sambrook Exhibition. In October 2013 she won the GQ Norman Mailer Student Writing Prize and will be published in a forthcoming issue of GQ.