You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

At the age of thirteen, Sinéad Gleeson found herself in pain: ‘The synovial fluid in my left hip began to evaporate like rain. The bones ground together, literally turning to dust’. She was diagnosed with monoarticular arthritis and missed months of school, her teenage years marred by long stays in hospital and numerous operations, including a major one to fuse her hip joint together with metal plates. Then, at twenty-eight, six months after she got married, she found out she had leukaemia. Although the outlook was bleak, Gleeson promised her mother: ‘I’m not going to die. I’m going to write a book’.

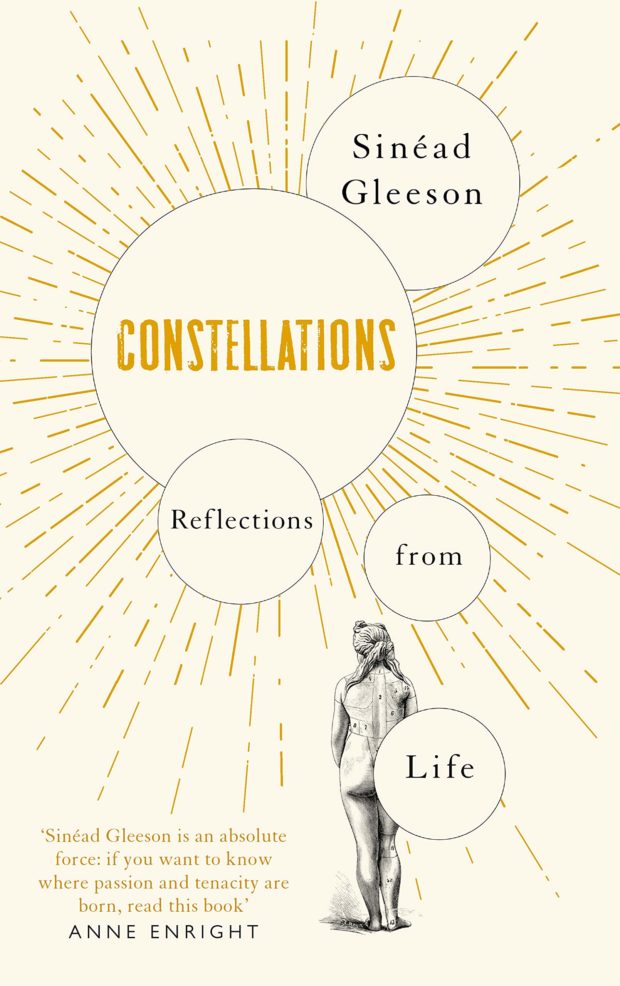

Constellations is that book, a collection of raw, beautifully charged, wide-ranging essays about living in an imperfect body, specifically a female body in Ireland, where historically women have been denied their right of corporeal self-governance. Gleeson knows that ‘the patient is never in charge’, and one feels this is particularly the case for women in an overwhelming male medical establishment.

When, as a ‘self-conscious girl’, Gleeson was made to wear a swimsuit while being checked for scoliosis and cried from the shame, her doctor threw her a towel and asked: ‘“There, is that better?”’ In one harrowing scene, she recalls how a doctor took a saw to the cast running from her chest bone to her toe tips. As ‘blade meets skin’ she feels ‘a scald of heat spreading’ but he tells her she’s ‘overacting’. Her mother, unable to withstand her screams, is forced to leave the room as ‘this man urges it on, like a horse in a race’. Years later, after the difficult birth of her second baby, a male surgeon responds to her complaint of terrible pain in her hips with the suggestion of ‘baby blues’.

Gleeson’s lens is close, intensely intimate, but devoid of self-pity. Her book – entitled Constellations for all the metal in her body, which she sees as artificial stars – is not a lament for her misfortune. Nor is it a triumphant account of recovery against all odds. It’s deeper and more interesting, a memoir of a body that radiates out to discuss politics, literature, art, science and history. Comparisons to fellow Irish writer Emilie Pine’s Notes to Self are inevitable: both books take in birth, death and grief, both writers are brave, wise and true. But Gleeson also sits alongside Maggie Nelson, Siri Hustvedt and Olivia Laing for the rigour of her debate and interrogation of ideas.

In ‘A Wound Gives Off Its Own Light’, one of the most dazzling essays in the collection, Gleeson explores the work of three women who transformed their damaged bodies into art: Frida Kahlo, Lucy Grealy and Jo Spence. She recalls finding Kahlo – who broke her pelvis, collarbone, ribs and leg in a bus accident when she was eighteen – while she was in hospital, similarly confined in a cast as a teen. Although reluctant to equate their suffering, she holds up Kahlo, alongside Grealy and Spence, as ‘lights in the dark’. Whereas she viewed her plaster cast as a ‘tomb’, Kahlo decorated hers, creating a language of beauty in place of sickness and death. Similarly, Grealy’s searing account of her deformity Autobiography of a Face and Spence’s unflinching pre- and post-surgery photographs are shown to be powerful acts of self-assertion and reclamation. By bringing the private world of sickness into a public space, these women refused to succumb and disappear, showing Gleeson that ‘it’s possible to have an illness and not to be the illness’.

The quest to find a language to express pain recurs throughout the book. In ‘Where Does It Hurt?’ Gleeson responds to the McGill pain index, a vocabulary-based scale developed by practitioners, with twenty poems exposing her unique, personal experience. One poem on scars depicts ‘a mouth sewn up with metal’. Another conveys the terrible heartburn she suffered while pregnant, her throat ‘hotter than coals’. In ‘Our Mutual Friend’ Gleeson intersperses prose with poetry to describe how her former boyfriend introduced her to her husband and then, at the age of twenty-four, died after a tragic fall. One gets the feeling that pain cannot be contained within neat, orderly sentences. Gleeson quotes from Virginia Woolf’s ‘On Being Ill’, showing how the sufferer must coin new words, ‘his pain in one hand, and a lump of pure sound in the other’.

Formal experiment is also evident in ‘60,000 Miles of Blood’, as Gleeson interweaves the history of blood-group identification with tales from art and religion, her own transfusions and her treatment for leukaemia. During chemotherapy, she takes a drug to stop her periods, ‘a moratorium on one aspect of being female.’

A woman’s right to govern her own body is addressed most powerfully in ‘Twelve Stories of Bodily Autonomy’, a fiercely argued essay about the 2018 referendum on abortion. Gleeson reminds us that ‘Ireland’s history – for women – is the history of their bodies’. From reproduction to sexuality to motherhood, women have been reduced to their physical form, their choices taken away, their freedom legislated against. By sharing the stories of women who have suffered and died, Gleeson shows that change has been hard won, that it has been paid for in blood. Taking her daughter with her to the polling booth, she reflects on how the change in law will affect the next generation and ends with a note of hope: ‘She takes my hand and we walk into the cool air of the hall, to change the future.’

Constellations contains a political spark, but it is a collection fuelled by acceptance and solidarity. Early in the book, Gleeson recounts a school trip to Lourdes where ‘in the shadow of the grotto’ she receives not a healing miracle but a kind of peace: ‘I know that I will go home, and that I will live with my imperfection; that my surgically altered bones will carry me through the years’. Despite her pain and suffering, the repeated betrayals and frequent operations, she is not at war with the body that has borne her two children. While Gleeson is right that ‘pain – unlike passion – has no commonality with another being’, there is unity in the way she links the fragments of life, the loose ends and tangents, the cycles of birth, blood, motherhood, death and ghosts. For pain is a human experience, one shared and endured by generations of women in their mortal bodies.

Constellations is out now from Picador.

About Jennifer Kerslake

Jennifer Kerslake is an editor and writer. Born in Devon, she now lives in London where she works for the Orion Publishing Group.

I found constellations dull and repetitive. I am sad she like so many has had a hard time with her body and the health care system, but we know! We’ve heard it all before…even the art she chose to highlight her ideas is now very mainstream because it has been soooo written about. Please…find a new angle. Her writing is accomplished and the style interesting.