You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shoppingCartography – the study and production of maps – is, by definition, a pioneering art. Charting the unknown is a job for the explorer; those not trapped by familiarity. As difficult as geographic mapping is, and traversing jungles is no small feat, the human psyche is arguably more treacherous territory. We live it together and live it alone, viewing the world differently, as one might see mountains in different hues from disparate places.

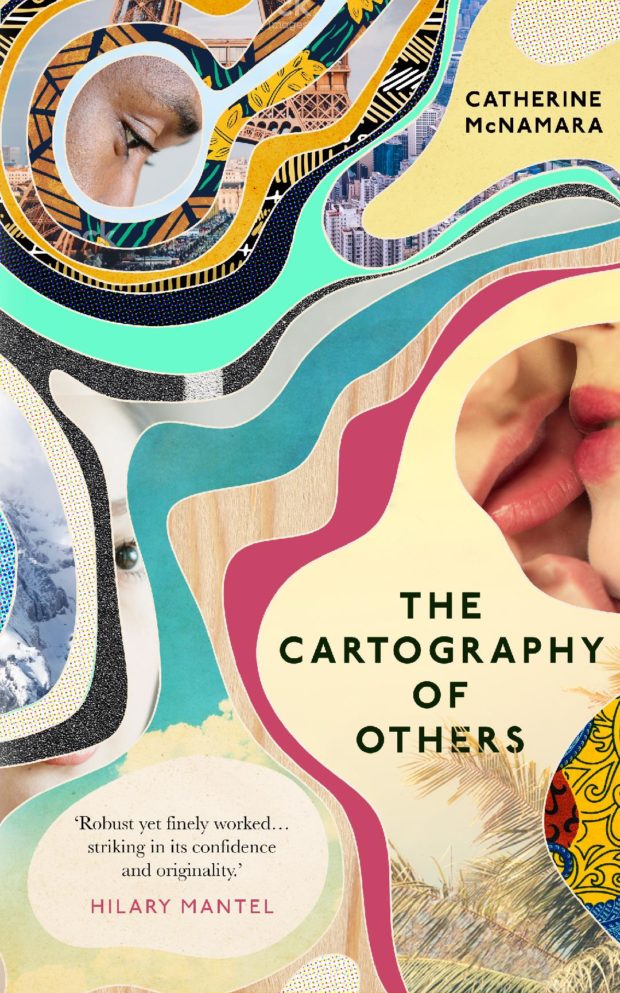

Catherine McNamara’s The Cartography of Others may take us to exotic locations but it’s no frilly “summer read” to be grabbed at the airport for Boonsian entertainment by the swimming pool. The “cartography” here is not primarily geographic. The backdrops are real and effectively drawn but it is in charting the contours of the human condition that McNamara succeeds with skilful interpretation.

This collection displays an incredibly descriptive art in conveying the tenuous tapestries of the soul. We become human through our interpersonal relationships with other human beings. The characters convey this longing for connection. Their emotions and lusts are so finely conveyed that the reader wishes the story would go on. Yet like all good things, they end, and the author knows how to leave a reader wanting more.

The first story in the collection, “Adieu, Mon Doux Rivage”, is a curious piece of observational art. Not much transpires in the linear narrational sense but it’s clear why McNamara chose to open the collection with this and it shows how she can do much with ostensibly little. A musician is on a summer boat trip around Corsica, where staff must adhere to his pretentious requirements. The story reveals how confusion and longing can erupt in apparent serenity.

The rich musician who books the cruise oozes the qualmish stench of the rich but boastful nobody. His strange relationship with a demanding Japanese wife is told in delicate brushstrokes. The geographic background is equally descriptive and the reader is drenched in a deep and exotic realism. “Adieu, Mon Doux Rivage” leaves the reader wondering if they’ve just spent five minutes glancing at abstract expressionism in a silent gallery somewhere in time.

McNamara continues to paint a myriad of human confusions and catastrophes in a delicate yet confident language, often making the physical background, however eventful, at times almost irrelevant. What matters in the cartography of others is not what others do but who they are.

Most of the story titles could easily have been Joy Division song titles, but not “Magaly Park”, where a coastal town is knocked out of balance by a homicide. Amid the sea breeze and urban familiarity is a palpable sense of societal fracture. Residents’ attempts at communication are stilted by a ubiquitous suspicious of human interaction.

The descriptions of the seaside with its gulls and lapping waves are still lush in spite of the chaos of crime. The story develops from an assumed crime story into a satisfying insight of the protagonist’s longing for the love of another woman. It ends with a wonderful escape into a rocky landscape that has metaphorical allusions of lesbian love.

Such observational interpretation of the human psyche demands strong, cutting prose and at times the light touch of a feather. McNamara is an expert at conveying gravitas with the briefest of sentences and somehow makes remote feelings seem emphatically our own.

With characters that are stunningly unique yet refreshingly accessible, the stories all seem to have a kernel of longing for love or lust. In a broader sense all want connection: the touch of a hand; the voice of a lost lover. Further stories analyse deeply the agony in watching a loved one suffer persistent domestic abuse at the hands of their spouse. Another piece watches a realisation unfold wherein cancer and disability have changed a relationship forever. We leave each story with a sense that however remote the feeling or improbably the odds, we’re never far away from pain or happiness in our own existence.

Today’s globalist and technological era perpetuates the idea of fewer divisions and less conflict. McNamara has a proclivity in taking readers to the wrong side of town, where dialogue is often snared by cultural and societal division. She seems not to consider our differences so easily erased. The concept of “foreign” is impressed as a real entity in a seemingly shrinking world.

The Cartography of Others charts a landscape of pain and hope that emblazons the strength and fragility of the human spirit. It is an atlas of distances and bridges between us. That readers may wish some of these tales developed into novels should come as encouragement to the author.

The Cartography of Others is out now from Unbound.

About David Stewart

David Stewart's background is in journalism both in newsrooms and freelance. He has done some sub-editing for nationals and reported for rural newspapers. David also enjoys reviewing the arts and reading all kinds of books.