You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

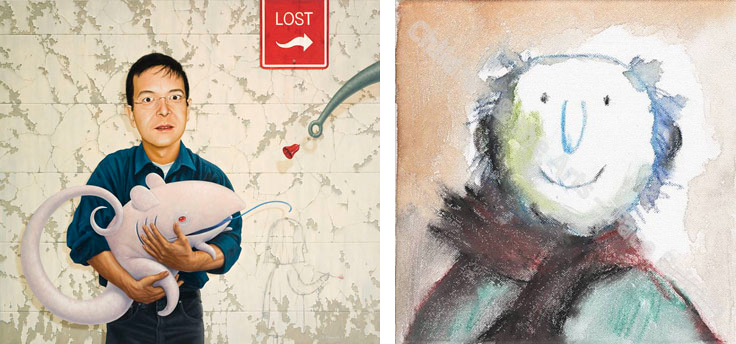

Last Monday evening, over a hundred comic fans turned up at the St Albans Centre for a discussion between two of the world’s best loved illustrators: Quentin Blake, the septuagenarian first British Children’s Laureate (1999–2001) whose work is synonymous with the stories of Roald Dahl; and Shaun Tan, winner of the 2011 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award and author and illustrator of The Lost Thing, which he also adapted into a 2010 Oscar-winning short animated film. Hosted by Comica, they discussed their respective career paths, creative process, and the idea of illustration as visual language.

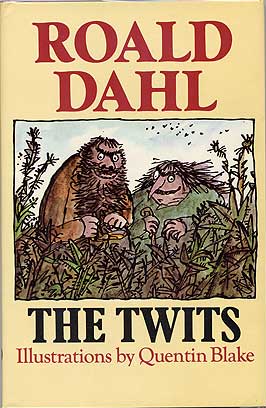

When Tan said to Blake, “I’m at an advantage because I grew up with your books,” the Melbourne-based artist touched upon something that so many of us can relate to. Blake’s illustrations are not only inextricably linked to Dahl’s work, but are also an important part of our growing up, in the same way that The Sound of Music or The Wizard of Oz have come to dominate our collective consciousness, even as we grow into adulthood. Tan was particularly disturbed by the offensively uncouth Twits when he was little, as many of us were, which goes to show how affecting Blake’s illustrations are. Poetic, scary, and imaginative, Blake is every bit as dexterous as Dahl, his frantic lines perfectly complimenting Dahl’s tales of childhood yearning and restless youth during their 13-year collaboration, up until Dahl’s passing.

Recently, Blake also did a series for hospitals in the UK and France—for children, for pregnant mothers, young people with eating disorders, and older patients with mental health issues—to create a more uplifting environment, which culminated in an exhibition at the Foundling Museum: As Large As Life [see video interview]. While drawing this series, he found himself tending towards drawing characters who are either flying or swimming. This doesn’t come as a surprise; throughout Blake’s career he has had a habitual tendency towards portraying characters in motion. As Tan put it, Blake’s characters exude a “nervous energy”, the texture of his watercolours adding a suggestion of fluidity.

It might be lesser known to some that Blake also writes and illustrates his own books, such as the award-winning Mister Magnolia and Clown. What Tan enjoyed about Clown, a book solely comprised of illustrations, was that the reader doesn’t know on what timescale the narrative operates. For Tan, this speaks of the special relationship between illustrated books and time. In his essay, “Picture Books: Who Are They For?” he wrote, “Readers can progress at their own speed, revisiting passages when they see fit; in illustration, time is less linear than in other art forms such as cinema or prose.” Unlike film and animation, picture books have no specific duration, so “you can look at things for as long as you want, and at any point without the pressure of linear narrative.”

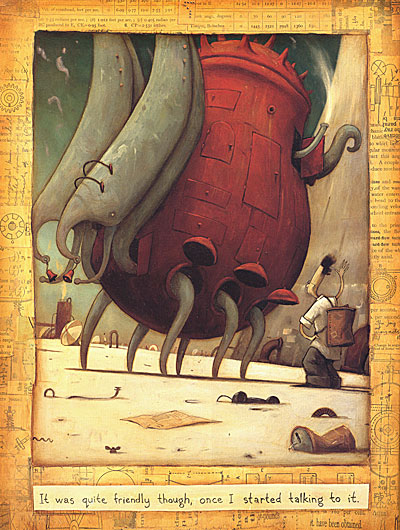

Tan sought a similar concept with his book The Arrival. The 2006 release focused on the immigrant experience (he himself grew up in the Australian city of Perth as the son of a Malaysian immigrant), in which he examines themes of belonging and attempts at communication through a lens of surrealism. Tan explained that if a drawing looks too real, he has to distress it in some way to spoil the allusion of reality. He strives to create a “parallel equivalent” to the actual object or event, aiming to evoke the emotional and experiential quality of an object or encounter rather than merely documenting its likeness, such that something less realistic can in fact be closer to the truth.

As a teenager, Tan drew to compliment his own science fiction stories, which were inspired by authors such as Ray Bradbury. Though his stories were less successful, publishers liked his illustrations. At sixteen, he began illustrating for science fiction journals. A fascination with creatures recurs throughout his career, which, he discloses, are often inspired by his pet parrot.

These creatures usually lack mouths, which is something he attributes to the underlying theme of communication. This struggle of developing an individual presence amongst adults is an integral part of growing up, and this feature of his work is a major factor of his success in children’s literature. The Lost Thing, for instance, is about a boy who discovers a funny-looking creature while collecting bottle-tops at a beach. The boy wants to help the creature find its way home, but when he asks his parents and the adults around him to help, he is met with indifference, as an unwelcome interruption to the routine of their busy lives.

Blake and Tan differ in their working process. While Tan begins with dark surfaces, building compositions over a number of layers, Blake described his illustrations as taking place on “stages without sets”. Blake’s finished compositions characteristically feature minimal backgrounds and some amount of uncovered paper, surely a result from working so extensively with pages accommodating text. This aspect is one which makes his work so accessible to children, who can see how compositions are constructed from the bare beginnings of a blank page. He starts by scribbling in pencil to establish a composition, and will then will apply ink to paper with a lightbox. He stressed that this process isn’t “tracing”, his intention not to reproduce but to work quickly with ink straight onto paper to preserve a fluid quality [see more here]. At this, Tan agreed that “total control is the enemy”, later noting that he tries to avoid digital means when working, favouring the accidents that occur through working with physical materials.

Tan also discerns two different approaches to art. The “golf swing” is a process of refinement, with each finished piece the last in a long line of different versions. While this may be Blake’s favoured technique, Tan falls into the “sedimentary rock” camp. Each piece of work is revised extensively, from beginnings using graphic pencil, then layers of acrylic paint, and finally oil paint.

Just like any kind of artist, it’s interesting to hear how much—or how little—of themselves Blake and Tan bring to their work. Blake believes that illustrating involves “a certain amount of acting”, and committing and investing yourself into the characters you’re working with to portray them convincingly. It’s this ability to create an immersive and entirely distinct world that has held the interest of so many children and adults throughout a long and celebrated career.

This little bit of acting applies to Tan as well. He confesses that perhaps he is so interested in travelling precisely because he has a very reclusive working life—the only time he gets to travel is to attend events such as this one. At the same time, Tan also draws upon personal experiences, such as with The Arrival, and soon again with his next book, which centres upon the relationship between two brothers.

This was a hugely enjoyable event and a rare chance to see two artists, who hadn’t previously met, and whose styles and age differ considerably. Particularly impressive is Shaun Tan’s personalised stamp used to frame his autograph—now that’s attention to detail.

About Emily Cleaver

Emily Cleaver is Litro's Online Editor. She is passionate about short stories and writes, reads and reviews them. Her own stories have been published in the London Lies anthology from Arachne Press, Paraxis, .Cent, The Mechanics’ Institute Review, One Eye Grey, and Smoke magazines, performed to audiences at Liars League, Stand Up Tragedy, WritLOUD, Tales of the Decongested and Spark London and broadcasted on Resonance FM and Pagan Radio. As a former manager of one of London’s oldest second-hand bookshops, she also blogs about old and obscure books. You can read her tiny true dramas about working in a secondhand bookshop at smallplays.com and see more of her writing at emilycleaver.net.