You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

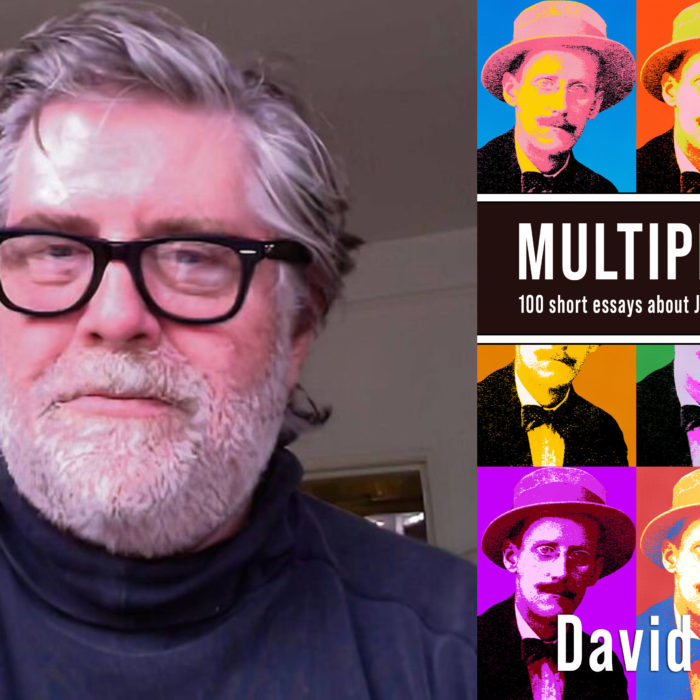

Novelist and short story writer David Rose claims to have abandoned fiction. In an interview on the Negative Press website in 2012, he was asked what he was currently working on and his reply was: “I am no longer writing”.

Since that announcement, there has been an acclaimed collection of short fiction – Posthumous Stories (Salt Publishing, 2013) featuring a selection of his work spanning 25 years and, more recently, a novel, Meridian – A Day in the Life with Incidental Voices (Unthank Books, 2015). One can only hope then that his comment from three years ago no longer stands.

I first came across David’s writing in 2011, in the first edition of Salt Publishing’s hugely successful series The Best British Short Stories. His story ‘Flora’, about a botany-obsessed older man who is befriended by a young woman, was a highlight of the collection: the writing was spare, precise and beautiful… and I loved it immediately. Around the same time, David’s first novel, Vault (Salt Publishing), was published – this experimental book about a world war two sniper turned competitive cyclist was told from two points of view: McKuen’s and a novelist writing an account of his life. The two narratives are in conflict and conversation with each other, and both are highly engaging and intriguing.

Because of my admiration for his work, I asked David a couple of years ago to contribute a short story for an anthology of Brontë-inspired short stories I was editing in support of The Brontë Birthplace Trust (Red Room: New Short Stories Inspired by the Brontës, Unthank Books, 2013). He didn’t hesitate and I was delighted when ‘Brontësaurus’ arrived, with its poignant tale of a man constructing a thesaurus of key-words found in Emily Brontë’s poetry. The writing, once more, was as taut as a fishing line.

Now, David’s second novel Meridian has just been published and again demonstrates his interest in language and ideas. The book features the hour-by-hour recording of a day in the life of an architect – trips on public transport, time spent at work, even a drink with an alcoholic on a bench. This narrative breaks off at 12pm (the meridian of the title) and an ‘a to z’ of incidental voices is introduced with the architect’s story then resuming post-meridian. It is impressive, wonderfully written and also very funny throughout.

AJ Ashworth: I understand that you started Meridian a while ago but didn’t know how to continue with it so put it away in a drawer for a while. Can you talk a bit about that and how you managed to get started on it again?

David Rose: After finishing Vault in 2004 – my first attempt at a novel-length work, which necessitated a different discipline from short stories, writing every day, in my lunch breaks as opposed to the late-evening writing that produced the stories – I thought I would continue the discipline and start another novel. I wanted something contemporary, and as that was the centenary of Bloomsday, I decided to update Ulysses, making it an exhaustive account of one typical working day. I didn’t want to plot it in advance – elaborate plotting amounts to predestination, which isn’t how we experience life. Rather, I wanted to capture the randomness of life, and ‘through-compose’, making up as I wrote each hourly section. I got to midday and it petered out; it wasn’t going anywhere. So I left it.

Around five years later, Vault – which was already in the bottom drawer when I abandoned Meridian, and had been there ever since – was resuscitated by Nicholas Royle, who liked it enough to pass it on to his agent, who in turn made valiant attempts to place it, without success. Nick felt its length – its brevity – was against it, and suggested I try to write a longer novel, around 60,000 words perhaps, which might be easier to place first. Having no new ideas, I pulled out the abandoned manuscript to see if I could salvage anything.

Being naturally lazy, I decided to leave what I had as it was, and find a new direction from the point of abandonment. I thought it might be possible to use the interest in randomness structurally, as a generating device, in the way the composer Harrison Birtwistle used computer-produced random numbers in his early compositions (this is alluded to in Meridian, when the architect attends a South Bank concert incorporating his music). Numbers work in music, but not in fiction, so I eventually hit on the idea of the homonyms – which are, as Italo Calvino says in discussing automatic writing – random collisions of meanings. I drew up a list of homonyms, selected one – a pair, in effect – from each letter of the alphabet, and they became the start and end points, acting as constraints that generated the narratives from that point.

Having got to the end of the chain reaction (to revert to the sub-atomic physics that governed the novel from its origin), and a resumption of the architect’s master narrative, I still had a lot of homonyms left which seemed too good to waste, so I found a way of using them up as switches, triggers, throughout the rest of the day’s narrative.

All well and good, and the idea produced the text, but Nick didn’t think the text worked, so it was abandoned yet again. It was resurrected a second time by a chance remark to the poet Caroline Clark, who then asked out of curiosity – or maybe politeness – if she could read it. When she did, she thought it might be possible, with some tinkering, to make it more accessible to readers, and made some changes, including a change of title, from the original Untitled to Meridian.

Having done this, she made mention of it on Facebook, whereupon Ashley Stokes, amongst a few others, asked to read it, and passed it on to Robin Jones, the other half of Unthank Books, who decided to risk publication.

So in an appropriately random manner, Meridian now exists in its resplendent jacket, by a series of accidents.

This answer seems almost as long as Meridian itself; my apologies.

AJ Ashworth: I was really drawn to the ideas about randomness and chaos which are present in the novel. For example, you describe a school playground as having “randomness of movement, a space of allowed anarchy between the straits of discipline”. And chaos is also present, particularly in the structure of the novel where the main architect’s narrative is ‘disrupted’ by the incidental voices in the middle. Can you explain a bit about these ideas and what interests you in them?

David Rose: Although, as I’ve explained above, randomness as a structural and generating device was a practical attempt to solve a practical problem, i.e. lack of plot and ideas, exacerbated by laziness, the metaphysical interest in randomness was there from the start. Reading up on Quantum Mechanics and Chaos Theory, it struck me that randomness exists in the universe at only two levels: the sub-atomic; and the human, where social interaction is complicated further by not just chance meetings but differences in mood, personality, ethics and so on. Thus even during the architect’s morning, details emerge of accidental meetings, such as the ticketless woman at the barrier, or with a client’s not showing up, some of which become relationships, some don’t, and prior friendships which have expired from the exigencies of time. So randomness is an essential element in the patterning of our lives.

When I resumed work on the novel, I read further in the literature of Quantum Mechanics, including Michael Frayn’s dazzling playscript Copenhagen, about the wartime meeting between Heisenberg and Bohr, once colleagues, now on opposing sides of the war, in which Frayn uses the Uncertainty Principle as a metaphor for the unknowability of others, and the ethical implications of that.

The school playground, I seem to remember, had to do with the idea of using probability to determine the flow of human traffic – stemming from the natural paths made on grass by people walking across a park – and applying that to public planning and architecture, which struck me as dangerous.

So the idea of randomness permeates the novel, and the governing metaphor of sub-atomic indeterminacy becomes enacted in the central, meridian section, as a sort of nuclear fission producing a chain reaction, each semantic collision setting off the next, until the circuit is completed.

AJ Ashworth: There is a line in the novel which says “words are wormholes in time” and I really like that, especially with regard to how you use words (homonyms) as wormholes into the worlds of the different characters in the incidental voices section. Can you say more about this?

David Rose: That idea only occurred to me when writing that section (as you’ll have gathered, none of the sectional narratives was pre-planned; that’s how the generating device operated), but it struck me then as encapsulating what I had been trying to do – the idea, again from theoretical physics, of the multiverse, an infinity of co-existing universes, which becomes strengthened in the afternoon and evening by synchronous switches across to any of the prior narratives, a reminder of all these personal universes co-existing beyond the consciousness of the architect.

AJ Ashworth: There is a lot of humour in the novel, in particular with regard to word-play. You seem to take a real delight in playing with language.

David Rose: Language is the medium we as writers work in, so we should naturally feel the need to play within it. We need, generally, a much more robust rebuttal of the post-structuralist, Barthesian nonsense spouted about language – as alienating, as oppressive, as the real agent, language writing the author – and a defence of the Leavisite view of language as the means by which humans come together, not just intellectually but socially, personally.

As writers, we can view language as the stuff we shape, as a sculptor shapes marble, which does encompass the experience of resistance, of a certain alienness to language, and it’s a valid description of the efforts of most of us. But although a natural medium, language is organic rather than monolithic; words bear the traces of human interaction back through time. There are still huge, untapped linguistic resources for writers to mine.

AJ Ashworth: You seem to have done a huge amount of research for this novel – in particular with regard to architecture. Did you know much about the subject before you started?

David Rose: Very little in any technical sense. I did have some entirely lay interest in the aesthetics of architecture as one of the visual arts, and had a few books on architectural history, particularly Modernism. But that was it. I did, as a child, own the box of bricks described in the novel, but later, as an adolescent, never gave architecture a thought as a career, despite taking Technical Drawing at school.

I did want to make the novel a typical working day, since most of us spend the greater part of our lives at work – Ulysses is a working day for Bloom, soliciting advertising space, although it’s noticeable that Bloom doesn’t get a great deal of work done. But to make my character a Post Office clerk, while not without literary precedent (e.g. Trollope, and the poet Lee Harwood), would have become too limiting, too complicated, too personal; and there is the Official Secrets Act to consider. I made him an architect, after some thought, mainly because I knew that whatever occupation I chose would involve research, and the research into architecture would probably be the most interesting, as indeed it was – I learnt a great deal about Green Architecture in particular.

I worried about how accurate the technical details of the novel would be, but luckily, had the reassurance of a qualified architect in the person of Myriam Frey, an excellent fiction writer herself – in English, although she is Swiss-German. She read a spin-off story, ‘Rectilinear’, then the pre-Carolinean manuscript of the novel, and thought it convincing enough. She is, therefore, the other dedicatee of the novel.

AJ Ashworth: I know you worked in the Post Office for many years. How has this fed into the novel and also your other work, with regard to inspiration and creating characters?

David Rose: It is, as a friend, fellow writer and writing tutor said to me, the ideal job for a writer: you encounter at close quarters an often friendly range of people from across the whole social spectrum. In my last office, in Richmond, Surrey, I could be serving Lord Watkins, Michael Frayn or Claire Tomalin one minute and a tattooed drop-out in for his benefits the next. So in Meridian, a number of the characters are based, however loosely, on people I had known as customers: the alcoholic gang, the Olympic diver (sadly now dead), the overweight man who becomes an undercover hotel inspector, possibly others.

In fact, I remember people and anecdotes from those years that I couldn’t have used without toning them down, because they would have been, in fictional terms, just too over the top. Real life will always trump the imagination.

AJ Ashworth: Is it true you’ve given up writing? If so, why?

David Rose: It’s true. I originally decided to give up at sixty, as I wasn’t getting anywhere. Then, when Nick Royle, acting for me after his agent gave up, placed my first novel with Salt, I thought I’d carry on. But when that novel, Vault, disappeared with hardly a ripple, it confirmed my original intention. There need to be radical reforms of the literary establishment, which aren’t likely to happen in my lifetime.

AJ Ashworth: Do you think it’s really possible to switch off that desire to write?

David Rose: It seems to be proving possible. Not to be able to give up writing would mean it’s an addiction, which is fine, but art as addiction is no longer art. Maybe I’ll come back to it at some stage. But I never regarded it as a career – it was, for most of my life, something I did in the evenings after a day’s work. My life has changed, my routine has changed.

There is a valedictory feel to the closing of Meridian, although it wasn’t intended at the time. I’m happy for it to be my swan song. But we’ll see.

David Rose’s short story ‘At Colonus‘ appeared in Litro #139: No Such Luck.

About AJ Ashworth

A. J. Ashworth is the author of the short story collection Somewhere Else, or Even Here (Salt Publishing), which won the Scott Prize, was nominated for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award and shortlisted in the Edge Hill Prize. She is the editor of Red Room: New Short Stories Inspired by the Brontës (Unthank Books), in aid of The Brontë Birthplace Trust. She has won Arts Council England funding and a K. Blundell Trust Award from The Society of Authors and is currently at work on her first novel.