You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

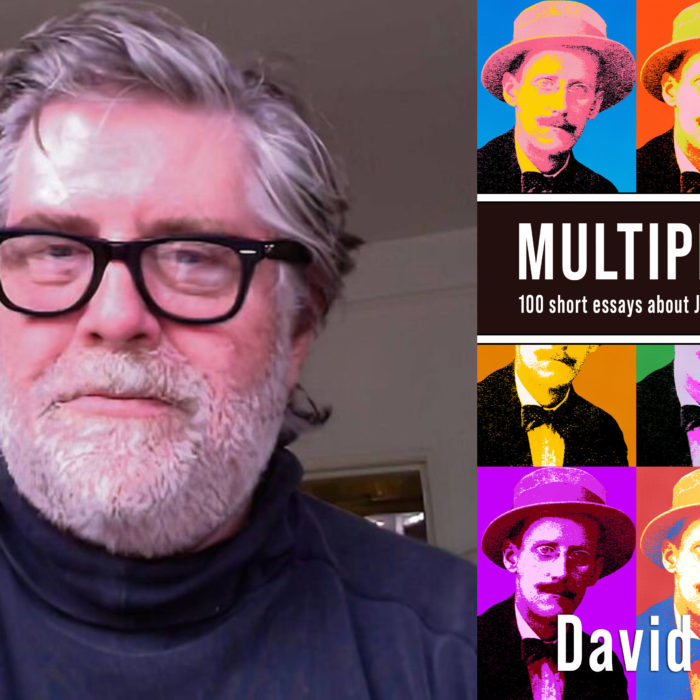

Litro’s Interviews Editor, Mia Funk speaks to the writers Geoff Dyer, Lydia Davis and Jonathan Safran Foer – all in Paris recently for the NYU Creative Writing Program. Geoff Dyer–the master of the engaging digression- about John Berger, his own first forays into fiction and the sister he never had, Lydia Davis on the pleasure of making; and Jonathan Safran Foer on the value of writing and the search for happiness. This interview has been edited for clarity and is taken from Mia’s own conversations and portraits of over fifty leading authors- that will form an exhibition called The Creative Process which will travel to universities and cultural centres in Europe and America.

Mia Funk: Your book Out of Sheer Rage begins as a book about D.H. Lawrence and then quickly veers off into something else, memoir, travelog, critique of the contemporary novel…That book was loose and natural and the digressions seemed like a deliberate choice. I was wondering if earlier in your career this tendency to digress was something you struggled with? You know, you’d start off writing fiction and it would become non-fiction?

Geoff Dyer: My first book was about John Berger, about whom I love so much, and I wrote this unbelievably boring academic book about him, which in many ways was an insult to this writer I love so much because that is not the right way to approach John Berger. And at the end of that I realised, well, I’m not going to do that again, so I guess that would have been the point after which I began veering off. And then in terms of fiction, I remember I was commissioned to write a book about the life I was living in Brixton in London in the 1980s, so non-fiction, and then it suddenly began drifting towards a novel and it was a time in my life when I was really––because I don’t have any brothers or sisters––when I was really wishing I had a sister. And I so remember, because my parents really insisted on me being so honest and truthful, I think the fiction writing thing I wasn’t well adapted to because I’m so honest. But I realised, suddenly, Oh god, this is what I can do. Since I wish I had a sister, I’ll invent one. I’ll invent the perfect sister for myself. And then I could sort of see what the lure of fiction was, really, like that. So, yeah, there it was, I had the absolute perfect sister. The perfect sister as envisaged by someone who doesn’t have a sister.

MF: I notice that your novels deal with how stories or the search for stories can provide solace. I’m wondering if this was true for you growing up?

Jonathan Safran Foer: I was with a child the other day who said she was shy and her parents said, “Well, you can write because writing is a nice antidote to shyness because it’s intimate and it’s private and it can be shared.” And that’s how I’ve always felt. Like when I write I am without anybody and it offers an opportunity to feel natural and to say things as I think they should be said, not for anybody else, but for myself and to arrange things as I want them to be arranged for myself and that’s true for anybody else––that’s recognised. And you’re lucky in a professional sense, but for us, you’re also probably unlucky in a psychological sense because in a funny way the solace depends on being esoteric. You know, like full sense of peace depends on a privacy and once it’s shared with other people it becomes vulnerable. It becomes exposed. That’s something I’ve had a difficult time with as a professional writer.

Lydia Davis: I don’t think of writing as solace so much as the joy of having made something and in that sense it’s not so different from the satisfaction of having woven a piece of cloth or thrown a pot or, you know, many other kinds of…I think of the creation of a written thing as taking a piece of experience and objectifying it in a form that pleases me. So it really isn’t a solace for me, it’s just the pleasure in having created that object outside myself. And it’s not true that writing about things makes them go away. So I can write about something and objectify it and still have the same thought over and over again. It doesn’t necessarily stop the thought.

JSF: And so what’s the value that is almost universally agreed upon, even if we disagree upon which painting we want to go to first, there is just something humanising about them, something that feels in the same way that certain acts of like religion or religious ritual are humanising when we need them. And I know that––unfortunately it’s in a moment of a kind of psychological or emotional need that I always return to writing. Always, always, always. Reading and writing and looking at art and watching dance, listening to music. When things are good, it’s okay. Because it’s the old saying, ‘Once upon a time there was a person whose life was so good there’s no story to tell about it.’ When things are good, it’s easy to forget what the point of all this endeavour is. When things are difficult, when you’re in a state of need, then that is what everybody reaches for. You know, whatever the form is for that particular person. So, in a funny way, the creative process is reminding oneself of that state of need. […]

I think in a way […] there is a tyranny of happiness and expectation of happiness constantly taking us off the path we probably would be better sticking to.