You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

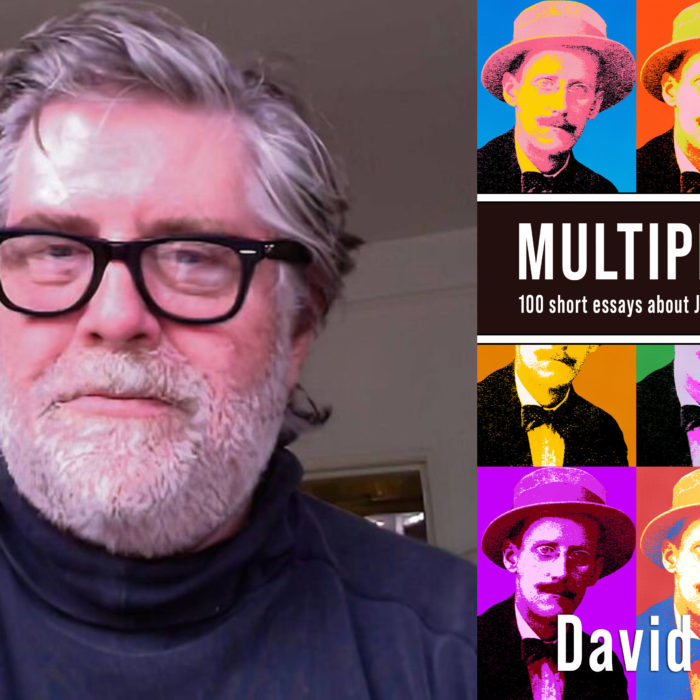

Go shoppingKele Okereke talks music with the acclaimed novelist and biographer.

Kele: Music seems to play a significant part in your work. You famously named The Rotters’ Club after progressive rock group Hatfield and the North. Where does your fascination with music come from?

Jonathan: I don’t know where it comes from, but if you don’t mind rewinding to the early 70s for a moment, I can tell you exactly what the trajectory was. The first piece of music I can remember being blown away by was ‘Fire’ by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. I saw them perform it on Top of the Pops in 1968, when I would have been six or seven. It’s a famous bit of footage, with Arthur Brown singing the song while wearing his flaming helmet, and it made the most incredible impression. Terrifying and exciting at the same time. But for the next year or two, my main love was rock’n’roll – real 1950s rock’n’roll, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis. The first album I bought, at the newsagents and general stores at the top of our hill (which also had a little revolving rack of LPs) was a Bill Haley compilation, which cost 15 shillings. Then in 1972 ELO did a cover of Chuck Berry’s ‘Roll Over Beethoven’, and I loved the way they had incorporated classical strings and bits of the 5th Symphony. So I bought their album ELO 2, which unlike their later records is an out-and-out prog album. Five songs stretched over 40 minutes, lots of apocalyptic lyrics and tricky time changes. And that was a terrible turning point for me. I gave up on the other bands I’d been listening to (Roxy Music, Mott the Hoople, Derek and the Dominos) and became a total progressive music freak. I started with the soft stuff – Genesis, Camel, Caravan – but after a year or two I was mainlining Henry Cow and Gentle Giant. Of course, progressive music more or less fizzled out in the late 1970s, and I moved on to other things, like Ian Dury, Television and Talking Heads, but soon after that, in the early 1980s, British pop music had a new generation of great songwriters: Paddy McAloon, Roddy Frame, Ben Watt, Morrissey and Marr. When I formed my band The Peer Group, these were the people we tried to sound like.

Kele: Your mother was a music teacher. What were your earliest musical memories?

Jonathan: My first memory of playing music was a terrible repetitive piano piece called ‘The Jolly Farmer’ which I was made to play over and over until I hated it with a visceral passion. I had a few piano lessons but I was always bad at reading music: I had no patience for sitting down and learning musical theory, all I wanted to do was improvise. My first guitar was a present for my ninth birthday, and using that I wrote my first song. It was called ‘Sunset’. It had three chords – A major, G major and E major – and one line of lyrics, “Oh, the sun goes up and the sun goes down”. That was it. A bit like T Rex, actually, who I was also very into at the time. As a teenager, as I said, I got into my proggy phase and discovered the delights of major sevenths and major ninths, these bitter-sweet, harmonically richer chords. Then one day my Dad brought home a record on the budget Classics for Pleasure label, an album of Ravel orchestral music. He’d bought it because he liked ‘Bolero’ (which I didn’t so much) but I listened to the rest of the record and heard these gorgeous pieces like ‘Pavane pour une infante défunte’, and realised that Genesis hadn’t invented these chords after all – it was Ravel and Satie and the composers of that period. So I became a huge fan of early 20th century French classical music – and still am.

Kele: Recently in an interview you stated that you “invariably find a line of melody more compelling than a line of thought.” With prose being an important part of your creative output how do you explore this distinction?

Jonathan: Well, as a consumer of words and music, if the two are combined in any way it’s always the music I listen to first. The melody speaks so much more strongly to me than the words that I don’t really pay any attention to them. If the most beautiful tune in the world was set to the blandest and stupidest words, it wouldn’t bother me very much. And I get just as much pleasure from listening to songs in a language I don’t understand as I do listening to songs in English. So when you have an artist like Bob Dylan, where the ratio of interest I would say is something like 95% words to 5% music, I’m afraid he does very little for me. However, as a (professional) producer of words and an (amateur) composer of music, I have to admit that my natural skills are weighted much more towards the former. In my songs and instrumental writing, I come up with fairly crude melodies, using simple chords and repetitive structures. Fine for pop music but not much else. Whereas my novels, I hope, are a bit more sophisticated than that. Or at least try to be.

Kele: As a teenager in the 1970’s, before the advent of home recording, you recorded the soundtracks of your favourite films on to two-hour cassettes, to listen to them over and over again in bed at night. How do you feel that way of listening to soundtracks has affected how you view the relationship between words and music?

Jonathan: It’s true, I had an obsession with Billy Wilder in the late 1970s and used to tape the whole soundtrack of his films onto C-120s, because of course very few people had video recorders at the time. And in that way I realised – which I don’t think many people have said about him – that along with everything else he had an incredibly sophisticated sense of how to use music in a film. In Some Like It Hot, for instance, the whole theme of cross dressing and role reversal is mirrored in Adolph Deutsch’s soundtrack music, where the different characters’ themes overlap and harmonise with each other in all sorts of unexpected ways, and form interesting counterpoints with the dialogue. I realised that by listening to the soundtrack at night, without being distracted by the visuals. And this is what prompted my own experiments with music and the spoken word, which includes my CD 9th and 13th (with Louis Philippe and Danny Manners), and live performances with The High Llamas, Theo Travis and Alex Maguire. And of course I’m interested in the possibilities of ‘books with soundtracks’, which is a growth area in the audiobook industry.

Jonathan: It’s true, I had an obsession with Billy Wilder in the late 1970s and used to tape the whole soundtrack of his films onto C-120s, because of course very few people had video recorders at the time. And in that way I realised – which I don’t think many people have said about him – that along with everything else he had an incredibly sophisticated sense of how to use music in a film. In Some Like It Hot, for instance, the whole theme of cross dressing and role reversal is mirrored in Adolph Deutsch’s soundtrack music, where the different characters’ themes overlap and harmonise with each other in all sorts of unexpected ways, and form interesting counterpoints with the dialogue. I realised that by listening to the soundtrack at night, without being distracted by the visuals. And this is what prompted my own experiments with music and the spoken word, which includes my CD 9th and 13th (with Louis Philippe and Danny Manners), and live performances with The High Llamas, Theo Travis and Alex Maguire. And of course I’m interested in the possibilities of ‘books with soundtracks’, which is a growth area in the audiobook industry.

Kele: You have spoken quite candidly about the relationship music has on your creative process and how you can often remember what you were listening to at the time of writing selected passages. Do you remember what were you listening to when you wrote What a Carve Up? What are you listening to now?

Jonathan: What a Carve Up is actually the least ‘musical’ of my books – it contains almost no references to music, so far as I can remember. But at the time of writing it, I was living in a studio flat with my wife, and she used to watch the TV at night while I sat at the table writing the novel, blocking out the TV noise with music on my headphones. But what was it…? Ah – I can remember one album, which came out at the time I was writing it – Dondestan, by Robert Wyatt. That would have been an appropriate influence because I’ve always been inspired by his way of combining music with a political consciousness. Right now I’m listening to Gary Burton on my iPod. He’s the most incredible vibes player – pioneer of the multi-mallet technique – and I’ve loved his music since I first heard it in the 70s. I stole the title of one of his pieces, ‘The Rain Before It Falls’ (composed by Mike Gibbs) for one of my novels. The iPod is on shuffle so I’m hearing stuff from every stage in his career, including his most recent album Guided Tour, which is almost a career-best: not bad for a 71 year old!

Kele: Who are the musicians living or dead that you most admire?

Jonathan: Among the living, Robert Wyatt springs immediately to mind. Paddy McAloon, definitely: his album from last year, Crimson/Red (released as Prefab Sprout but actually a solo album) is total genius from start to finish. Sean O’Hagan of The High Llamas who combines experimentalism with accessibility, as I’ve tried to do in my books. Louis Philippe, who writes the most seductive and sophisticated melodies. Gary Burton and Pat Metheny, true pioneers who never lose sight of the need to give pleasure to their audience. Lars Horntveth of the Norwegian band Jaga Jazzist, a great composer. Michel Legrand, still going strong. The list is endless, but melody is the constant. Among the dead I’ll just mention one figure, the Franco-Swiss composer Arthur Honegger, composer of five great symphonies which tell a kind of musical history of the upheavals in Europe during the mid-twentieth-century, which ought to be revived and played much more often. He was also something of a musical prophet, and is the author of one of my favourite quotes about music. In 1951 he said: “Noise benumbs our ears… and I truly believe that a few years from now we shall detect no differences except between large intervals. We shall lose sight of the semitone, and arrive at no longer perceiving anything but the third, then the fourth, finally the fifth. Rhythmic shock increasingly plays the predominant role and no longer the sensual delight in melody. At the rate at which we are going, before the end of the century we shall have a very scanty and barbaric music, combining a rudimentary melody with brutally stressed rhythms – marvellously suited to the ears of the music lovers of the year 2000!” Which is essentially what most pop music (with plenty of honourable exceptions, of course) has become.

Kele: You’ve played live as a musician before in The Peer Group and Wanda and the Willy Warmers, as well as playing keyboards on ‘In the Land of Grey and Pink’ by the psych rock band Caravan. Have you ever thought about releasing your own music as a solo artist?

Jonathan: Yes, I have, but I’ve always pulled back. But recently I’ve been getting braver, and also trying to bring myself more up to speed with new technology, so I’ve been making some home recordings using Ableton Live. Very primitive stuff, really. I’ve put together about an hour of quiet, ambient instrumental pieces (think Penguin Cafe Orchestra, maybe) and might upload them to iTunes or somewhere soon. And they’re also going to be performed live in Italy, by a group called The Alba Project, at the Collisioni Festival on July 20th. I’ll probably play a bit of piano and guitar with them. We’re on the same bill as Neil Young and Deep Purple, which is kind of a weird state of affairs. And over the last three or four years, The Peer Group have been re-recording some of their old songs, along with some new ones. We have an album ready now, called ‘If You Have To Ask, You Can’t Afford It’, which should be on iTunes any day now. There are ten songs, five of them written by me. (The music, I mean: I’m not very good at writing lyrics, I leave that to my friend Ralph who is a poet and also our drummer.)

Kele: In the past you have collaborated with The High Llamas for a special performance. Do you have any plans for any more collaborations?

Jonathan: I did a performance with Louis Philippe and Danny Manners in Deauville last month, reading two longish stories for which Danny had composed the music. The audience was a bit sceptical at first – I do tend to find people are very prejudiced against these words-and-music collaborations – but we won them over in the end because the music was so powerful, and its relationship to the words was so carefully premeditated and rehearsed. I think people were expecting to hear some free jazz musicians squonking away on saxophones in the background while I read over the top of them, and were pleasantly surprised there was more to it than that. So yes, we do hope to do more of these shows, and I’m also working on further collaborations with Theo Travis, since my words and his repetitive flute phrases and looping seem to go together well. Sadly I don’t think my collaboration with The High Llamas, ‘Say Hi to the Rivers and the Mountains’ – which is the most ambitious thing I’ve done in this area – will get another outing. It’s a full 50-minute dialogue-based piece for three actors and a six-piece pop group, which alternates songs with instrumentals and weaves spoken words into the music in a very intricate way, and it’s just a bit too complicated to rehearse and put on, given that there is no big audience for this sort of experimentation. We did shows in Dublin, Spain and a few other places – including the Latitude festival – but sadly the best show by far, at King’s Place in London in autumn 2012, never got recorded, which means that we don’t have a good record of the collaboration to release on CD or put online. But we live at a time when everything is over-archived, and perhaps sometimes it’s nice for things to vanish in this way: for something to have its moment, and then just disappear into the ether…

Jonathan Coe is the author of ten novels, including What a Carve Up!, The Rotters’ Club and Expo 58. His biography of BS Johnson, Like A Fiery Elephant, won the Samuel Johnson prize for non-fiction. His performance work has involved collaborations with many musicians, including Louis Philippe, Danny Manners, Theo Travis and The High Llamas.

About Kele Okereke

Kele Okereke is the lead singer of Bloc Party, one the UK's finest bands. Having sold over 3 million records with Bloc Party, he released an acclaimed solo record called The Boxer. When not touring with his band he travels the world extensively as an electronic music DJ. He studied English Literature at Kings College in London and has written articles for the Guardian, Vice and Attitude magazine, as well as having a selection of short stories published for Five Dials, Punk Fiction and Litro magazine. He is working on his debut novel. He currently lives in South London and has a 6 month old british bulldog called 'Olive'.