You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping Litro: The Southern Reach trilogy draws heavily upon nature and the wilderness for its horror. What inspired this direction for the books? What do you find horrific about the wilderness?

Litro: The Southern Reach trilogy draws heavily upon nature and the wilderness for its horror. What inspired this direction for the books? What do you find horrific about the wilderness?

Jeff: I’d wanted to write about the American South for a while, but the way my imagination works I knew it wasn’t going to be as directly as some novelists might tackle that landscape. My way in was through the 14-mile hiking trail here in North Florida that I’ve walked for almost 20 years now. Complete with a lighthouse just like the one in the Southern Reach novels. I’ve jumped over alligators out there, been charged by wild boars, been heckled by an otter, and also encountered a Florida panther. This last experience was particularly life-changing and profound because you simply stand there and you wait for the panther to kill you and eat you or go away. You don’t really have any options. It’s a unique wilderness area, too, in how it transitions from pine forest to swamp to marsh flats and then the beach. That lends itself to a layered experience in fiction, and there’s no detail of the natural environment in Annihilation, Authority, or Acceptance that’s second-hand. All of it is lived experience—things I’ve observed.

I don’t find anything horrific about the wilderness, and indeed the Southern Reach novels might be seen as books in which most of the wildlife is doing just fine. It’s human beings who aren’t doing as well, and that’s because we’re divorced from the natural world to a greater extent now than at any point in our history. This is one of the key reasons why we’re in such a problematic place regarding our own future and the planet’s future. A study released in 2010 indicated that, for example, US children grown up developmentally challenged about animals and the natural world. That’s the truly horrific thing: that we no longer fully belong on Earth, or function as a productive part of our world. This needs to change or we will find ourselves rudely and swiftly replaced.

Litro: Do you consider this to be a horror trilogy? Why/why not?

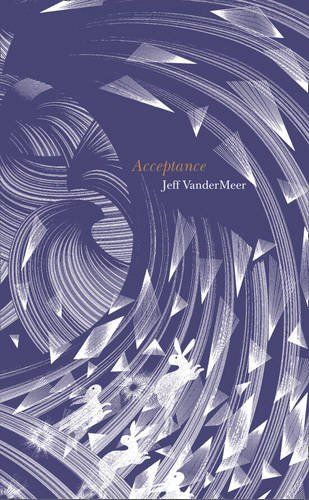

Jeff: There are always horrific elements in my novels and comic elements as well. My favourite novels, like Catch-22, combine all sorts of emotions and textures because that’s the way life is. It’s hypocritical to look away from the disturbing things in our world but it’s also wrong to ignore the absurd and hilariously ridiculous elements as well. And the heroic bits as well—Acceptance, the final volume, I believe exemplifies this. And the real horror isn’t from anything uncanny in these books, really, but in the grotesqueries of human institutions when they’ve been subverted or sociopathically twisted. Which happens all too often.

Litro: All three books draw from a variety of sources, from the castaway weirdness of Lost to environmentalists’ concerns about the state of our planet. What were your inspirations for the trilogy?

Jeff: Semiotext(e)’s Intervention series, including The Coming Insurrection, was a huge influence. But also Tove Jansson’s Moomins in Midwinter and her The Summer Book, for a certain tone in parts of the third novel, Acceptance. Kafka, of course, in stories like ‘In the Penal Colony.’ The nature poetry of Patiann Rogers. The Book of Miracles from Taschen. The nature books of Rachel Carson and Philip Hoare’s The Sea Inside. Iris Murdoch’s The Sea The Sea. Really, a lot of different books. Stepan Chapman’s amazing The Troika showed me, fictionwise, how to take risks and I couldn’t have written these novels without that in mind. Stanley Kubrick’s films, too, including his version of The Shining and Clockwork Orange—things about the staging and cinematography. Early influences like Angela Carter and Vladimir Nabokov and Deborah Levy are still with me, too. But, more than anything else, my experiences in the natural world, and my experiences observing my father navigating through the world of science.

Litro: What’s it like having a partner who’s also involved in the publishing industry? How much do you influence each other’s projects?

Jeff: My wife Ann is the only person with whom I can discuss my fiction while I’m writing it. Anyone else, and I never finish that piece of fiction. So throughout writing the Southern Reach trilogy we would go out on the porch with a glass of whiskey and we’d talk out certain scenes. If I was at all stuck, I’d just explain the situation and the characters involved and Ann would give her opinion about what might work or what reactions didn’t make sense. She was invaluable in that way as I could fix things before I even wrote the scenes in question. And she bounces things off of me on her editing projects—asking me to read stories, for example, that she’s considering. Although to be honest the last couple of years it’s been more one-sided in terms of me going off to finish these novels and she taking work off of my plate on jointly edited anthologies.

Litro: What music/art/TV/film/whatever is exciting you right now?

Jeff: I’m pretty high on a lot of series, like Orphan Black, Masters of Sex, Mad Men, Rectify (first season), Justified (first five seasons), among others. I haven’t seen many movies of late, to be honest. I’ve mostly been reading mainstream lit: Evie Wyld’s awesome. So is David Peace. Deborah Levy’s latest collection I like a lot. Smith Henderson’s Fourth of July Creek is a stunning first novel. Lee Rourke’s Vulgar Things I find pretty interesting so far. I also finally read Margaret Atwood’s Oryx & Crake and loved it. So you’ve caught me at a time when I’ve been pretty well immersed in some great non-speculative fiction.

One thing I would say that disappoints me about the less outstanding fiction I’ve read: a lack of understanding of our current perilous condition. That’s either near-future SF that ignores global warming to some extent, or mainstream literature that ignores that we live in a science fictional future right now. Which is to say, we are undergoing a kind of slow collapse and crisis right now but much “literary” fiction could as easily have been written 30 years ago with a few changes in the kind of phones being used. You just would have no clue about the modern experience from these novels—and maybe that makes them more universal in the long-run but it makes them less relevant in the here-and-now. Granted, it’s probably worse that a lot of future SF is so escapist or bereft of being willing to deal with our present, either. Indeed, Oryx & Crake, despite being written a decade ago, strikes me as still fiercely relevant to our current situation, which is a rare thing.

Litro: Do you have any deep personal fears?

Jeff: Other than sometimes a sense of claustrophobia in crowds, only a phobia about cockroaches. But that’s because small ones used to burrow into my ears as a child when we lived in Fiji. You’d wake up to this crunching sound in your ears… Otherwise, not much.

Litro: And finally… what can we expect to see from you next?

Jeff: I’m very much focused on touring behind these novels and writing nonfiction on nature and environmental topics because of the novels being out. But the next novel is likely Borne—kind of like a Chekov’s play in the round in the foreground while the equivalent of Godzilla-vs-Mothra goes on in the background.

Jeff VanderMeer is an award-winning novelist and editor. His fiction has been translated into twenty languages and has appeared in the Library of America’s American Fantastic Tales and in multiple year’s-best anthologies. He writes non-fiction for the Washington Post, the New York Times Book Review, the Los Angeles Times, and the Guardian, among others. He grew up in the Fiji Islands and now lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with his wife.