You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

He sees his mother at three-month intervals, during which visits he allows her, as he allows no-one else, to trim his hair.

Always a smiling but speechless client, verbally unresponsive to the questions and prompts so well attributed to stereotypes of barber, hairdresser, and stylist; always suspicious of more enthusiastic and cacophonous scissor-work – he prefers this arrangement, for if he is to listen to anyone in silence, if he is to smile politely, lost or found, in or out of thought, to hear narrative and commentary and hortatory exposition delivered over his shoulders from the lips of anyone, it might as well be his mother.

There is a tenderness in the operation that cannot be found in meeting for coffee or eating together, which occasions are only faintly marred by comments on his diet, political differences, and more or less automatic exhortations for him to ‘be careful’. As a grown man, he has the same horror of being mothered that he had when he was a child.

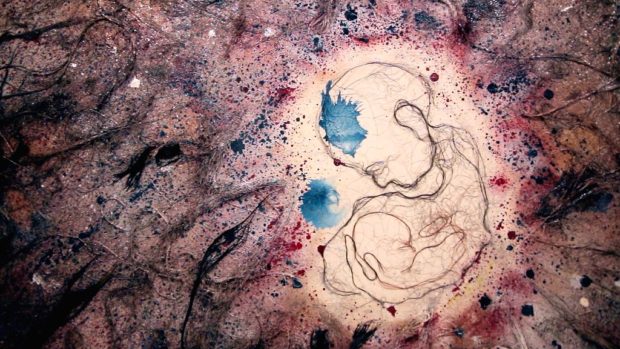

This way, a mother is permitted to touch her son and a son is permitted to be touched by his mother. She may handle his curls and relive the haircuts of his infancy and childhood, before adolescence wrought its inevitable rejection – haircuts themselves so similar to this: he, silent, absorbed in the goings on inside his head; she, voluble, absorbed in the goings on upon it.

A dining chair – in a square of good, natural light. Throat Velcroed into polyester gown. Hairdressing kit unrolled on dining table. Moistened ringlets collecting in lap. Cool mist of pump spray, sighing and hushing. Eyes protected by visor of hand. Typewritten phrase of each volley of chops, or the tentative percussion of shy maracas. This the careful scissor-work of one for whom time is not money, but time – for whom the end of the operation, presupposed by its beginning, nevertheless wants putting off a while.

She works, as always, without a mirror. She positions his head like the head of a marionette, bidding his biddable chin with the encouragement of a single finger, confident that it will stay right where she means it to stay, that it will not bow or rise in involuntary pessimism or optimism, that it won’t lean to one side or regress to the mean.

And she is an expert in minimalism, according to his wishes, taking her time and expending great effort and concentration on achieving almost nothing. For afterwards, the curls remain – he looks only a little tidier and shapelier, like a cat after a brush.

His experience of his mother has become inseparable from the sympathetic caresses of fingernail and steel, punctuated, more so each time, by telling little jabs and scratches, for which she no longer apologises.

About Jérôme Pearce

Jérôme Pearce lives, writes and teaches in Manchester. A graduate of the Creative Writing MA at the University of Manchester, he is currently working on his first novel. His work has appeared in PLU Magazine and Belleville Park Pages.