You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

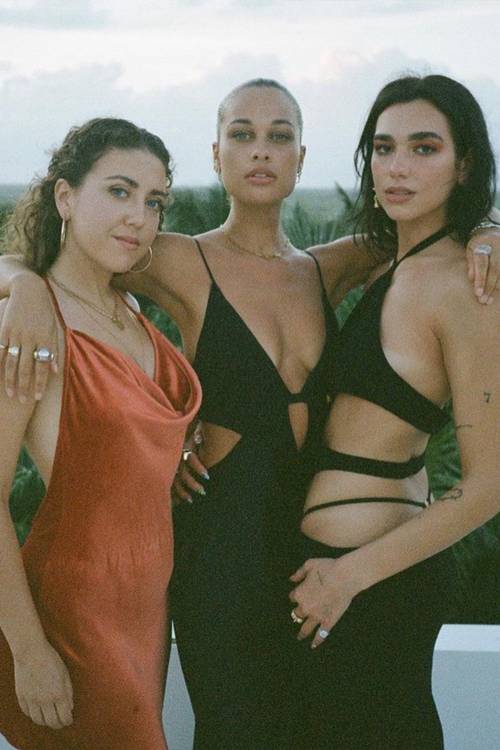

Photo @Dualipa

I dream of discomfort. For a year now I have lived a hazy half-life of wool and fleece and sweatpants. My feet, once calloused, are infant-soft. My waist, once cinched, is unharnessed. And my spirits, once hopeful, have faltered.

But as the COVID-19 vaccine rollout gets underway and a post-plague world glitters in the near distance, clothes are about to get uncomfortable again. And while our rested feet and pandemic-rounded stomachs may lament the return of high heels and tight jeans, I’m celebrating the coming constriction as proof that normality is once more in sight.

Because while 2020 was the year of the nap dress, the duvet coat and the slipper as shoe – shapeless, snuggly and highly practical items which cushioned us against the sharp corners of our new reality – 2021 promises something entirely different. Between midriff flossing, the return of the G-string, the rise of restrictive corsets and the towering platform heels spotted on the Valentino catwalk, the coming months will be defined by sartorial discomfort.

While shaking off our slankets might feel alarming after a year of collective confinement, uncomfortable clothes herald a return to normal social interaction. That’s because clothing is our most immediate way of communicating with the outside world, and whether we consciously recognise it or not, we all dress for an audience. Over the past year, we’ve had no or few spectators to our lonely existences.

In an open society, clothing performs two key functions: the practical and the performative. We wear clothes for warmth, comfort and decency, yes, but we also use garments as social codes to be deciphered by those around us. Clothes communicate our moods, identities and status.

Sometimes building a public persona requires personal sacrifice (squeezing into Spanx, needling ourselves at the tattoo parlour, feeling goosepimples on bare legs in breezy weather). But like so much in our lives since the outbreak of COVID-19, clothing has grown narrower in scope recently, its purpose reduced to the merely functional as we embrace comfort over communication.

But things are changing. We may still be wearing fleece-lined loungewear for now, but a desire to rediscover the performative power of clothing is emerging. Corset tops trend alongside tracksuits at online retailer Asos. The most-liked items at Urban Outfitters include fluffy sandals and roomy sweatshirts, but also cut-out rompers and structured dresses. Instagram influencers like Aimee Song switch between at-home snaps in sweats and PJs and street shoots in tailored suits and leather trousers.

Some may balk at returning to uncomfortable clothing after a year of casual comfort. But as we tentatively begin to socialise with friends, colleagues and strangers, we will once more need to need to speak to the world through our clothing.

“Don’t laugh but I have still been wearing my suits,” British designer Paul Smith told The Guardian of his lockdown uniform. I’m not laughing. Wearing a social uniform without anyone to witness it may sound ludicrous, but doing so has very likely helped keep Smith connected to who he once was, and who he could become in a post-pyjama world.

“Fashion is free speech, and one of the privileges, if not always one of the pleasures, of a free world,” as American writer Alison Lurie observed in her 1981 book, The Language of Clothes.

So here’s to the tapered bustiers, the exposed abdomens, the post-virus revenge heels – the individual pain that proclaims shared pleasure.

About Clare Kane

Clare is a fashion writer and novelist based in London, and is particularly interested in the social, cultural and historical reasons behind why we wear what we wear. She is the author of Chinese historical fiction novels Dragons In Shallow Waters and Electric Shadows of Shanghai.