You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

All it takes is a quick stroll around central London to demonstrate that its history is etched in stone. Amble past Cannon Street station and you’ll come across one of the oldest examples of this, London Stone. Housed at number 111, the landmark has sat and watched Londoner centuries sail by. In October 2018 the stone was returned from the Museum of London to its rightful place following some building works. Now, those City commuters and passers-by rushing to and fro can decipher a Braille plaque highlighting the otherwise nondescript piece of rock sat on its plinth outside one of the busiest underground stations.

The stone is shrouded in myth; although there are a trickle of competing theories, nobody knows the purpose of the stone. We don’t know now and we didn’t know four hundred years ago, when the stone first became widely written about. It was notable enough in the late 12th century that the father of the first mayor of London was named after it. We see it turn up in the writing of Williams Blake and Shakespeare, from which we might glean some hints of its function. Shakespeare, in Henry VI Part 2, has Jack Cade strike the stone and proclaim among his followers his intentions to usurp the throne of England, leading some to believe that this is how historical kings announced their entry into the City of London. This idea is rooted in the Norman history of London as a guild separate from the authority of The Crown.

Blake conceives of the stone as the remnants of a pagan sacrificial altar from pre-Roman ages. In his poem Jerusalem, he depicts it as the site of human sacrifice where the founder of the city sits to dispense brutal justice. Both poets have hit upon the common theme of the stone being a site of grand public announcements. This idea also turns up in an obscure Anglican tract titled Pasquill and Marforius, where critics of the 16th-century puritan church fathers are invited to post their denunciations upon the stone.

As for its origin, analysis of the rock has demonstrated that it is limestone from the Midlands. Rock typically taken from Rutland, England’s smallest county, was used as construction material by the Romans and their Saxon successors. Building on this, archaeologists have speculated that London Stone was once a foundation piece of a Roman gate or administrative palace known to have lain on the site now occupied by Cannon Street station. Also to be found here are the ruins of London’s Temple of Mithras which was positioned on the banks of the lost river Walbrook. Mithraism was a mystery cult introduced to the British Isles by Roman soldiers posted in what is now modern day Turkey. Its rites aren’t known to us, though they involved ritual animal sacrifice, imagined by William Blake.

It is not too much of a stretch to imagine that the stone may possibly have formed a section of the temple, which was excavated in 1954. We know that the stone has previously been cannibalised for the production of other buildings of worship during its history; being inserted into the design of the now-demolished St Swithin’s church (also designated as St Swithin at London Stone).

My conception of the stone has always been in line with the conceptions of the writers Ernest Rutherford and China Mieville, as the heart of London. Rutherford has the stone set in the wall of the Governor’s Palace. Here it is the central signpost for all the roads in the city. For his version, Mieville takes a more mystical approach. In his fantasy novel, Kraken, the stone is the literal beating heart, whose low pulse is felt across the city and watched over by a mystic cabal of protectors. Those, like Iain Sinclair, interested in mysticism and sacred geometry, will be pleased to read that the stone sits upon several ley lines running through the city. No matter the conception, these passages, byways and alignments all converge on Cannon Street.

Positioning the dead centre of London is contentious. If you balance a map of Greater London on a pinhead, the centre of gravity sits near Frazier Street in Lambeth, a fact hard to swallow for anyone who lives on the Northern banks of the river. City and borough mileages are traditionally measured by their distance from Charing Cross, based on the funeral procession for the Plantagenet queen of Edward I (a.k.a. Edward Longshanks, the Hammer of The Scots). This focal point lies in the much younger City of Westminster, which is almost certainly predated by the erection of London Stone. Westminster was built in the mid-11th century, while London lay a ghostly ruin downriver. Eleanor of Castile, King Edward’s wife, died in 1290; over a century after the stone was a well-known landmark.

For me, the London Stone is the obvious nucleus of England’s capital. It lies adjacent to our oldest landmark (the mithraeum). Any ignorance of this is the typical neglect of London’s more affluent north-westerly looking population. If we do not know what its purpose was for a millennium, let us go into this next thousand years by giving London Stone a new lease of life.

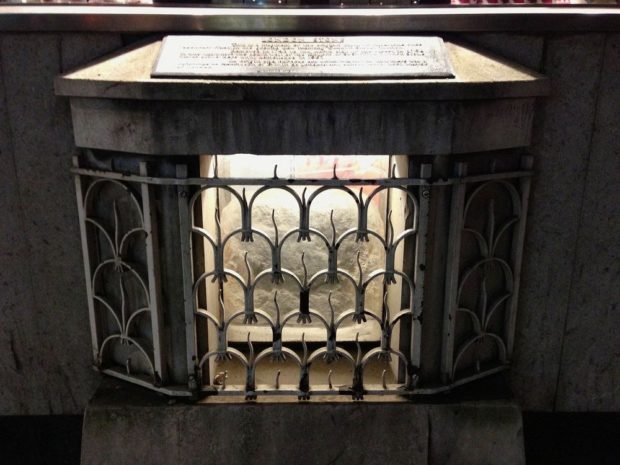

To celebrate its restoration, I went to pay respects to the monolith. This was a muted affair; exiting Cannon Street station under a grim November skies. We navigated the bustling crowd and crossed the road to the reliquary plinth where the soot-smothered stone has been restored. The waist-high mount is fairly non-descript. Nearby, an artist has set up shop on the street to sketch several portraits of the stone. Dodging well-dressed businessmen, our eyes squint at the panel detailing London Stone’s known history and whereabouts. With this observation over, the crowd envelops us as we make our way down the road to the Temple of Mithras.

About George Aitch

George is writer from Blackheath. He has written for The Guardian, Litro and The British Journal of Psychiatry. You may find his work in print and online in places such as Storgy, Bunbury Magazine and The Crazy Oik among others. His essay ‘What Do You Do When It All Goes Wrong’ was recently shortlisted by Ascona.