You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

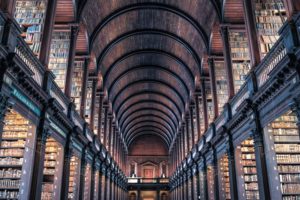

Go shopping The reading rooms of rare book archives smell of old paper, wood polish and something else unnamed, which may be the scent of the past, preserved and pickled. No sunlight is allowed to enter, and even the artificial lighting is muted. It is also always cold; old paper does best in air-conditioning and I am told that it is practically freezing down in the vaults where the books are actually stored. It is quiet too – not even the pages rustle, and the other scholars and librarians walk on tip-toe, it seems. After an hour or two I long for daylight, for summer, for a sound-filled here and a messy now. I am partly a Shakespearean by trade, a Renaissance scholar who studies English drama – the past alternately fascinates me and weighs me down. I want to linger with it; I want to shrug it off, get up and leave.

The reading rooms of rare book archives smell of old paper, wood polish and something else unnamed, which may be the scent of the past, preserved and pickled. No sunlight is allowed to enter, and even the artificial lighting is muted. It is also always cold; old paper does best in air-conditioning and I am told that it is practically freezing down in the vaults where the books are actually stored. It is quiet too – not even the pages rustle, and the other scholars and librarians walk on tip-toe, it seems. After an hour or two I long for daylight, for summer, for a sound-filled here and a messy now. I am partly a Shakespearean by trade, a Renaissance scholar who studies English drama – the past alternately fascinates me and weighs me down. I want to linger with it; I want to shrug it off, get up and leave.

The British Library in London, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC, the Newberry in Chicago – I have been to all of these archives in my quest for “primary sources”. I have hunted them down like an explorer doggedly looking for the mouth of a river. I have painstakingly read and taken notes from them. I will write an article or two if I am lucky enough to stumble upon a trove of archival treasures and bright enough to have a few good ideas. I might even produce a scholarly book – a shiny new one born of these revered relics.

Although I am never sure of my place in these grand old libraries. Truth be told, I sometimes wonder what I am doing in them even and why I am studying the far away and the long ago. We from India don’t really revere the past (our many gods, always worthy of reverence, are beyond history) – the walls of our ancient monuments serve as public urinals; street urchins play cricket in tombs centuries older than the books in these libraries, cheerfully oblivious of the ghosts pressing around them. NO BALL… they cry, and, OUT! And the past slouches over and listens, envious of the quick and the living. So why do I care about the dead? The answer varies with my mood and is not really worth going into – but for now I brood over my book (first edition, 1564) and think that everyone else working in these archives seems more bona fide than me; scholarly and sincere, zealous in their explorations. The librarians look formidable. They, like the other scholars, are nearly all white. Many of the men wear suits. I envy them because my arms are freezing.

At the Folger, the men and women who check our bags at the door smile and make small talk. They ask me where I go for lunch; they tell me about a Pakistani restaurant close by where I can get the best nan. They are not particularly interested in my research project or what I am working on, and I am thankful to them for that. When inside, and when the librarian brings me the book I have requested, I find that the soft cotton gloves I am sometimes required to wear before I touch the pages are too big. The supports and book weights I am provided with irk me. Of course, I am being completely unreasonable, of course, of course . . . But somehow, sometimes (only sometimes) this painstaking effort to preserve provokes in me the contrary wish to deface. I am tempted to write in one of the hallowed pages, to scrawl I WAZ HERE – big, bold, black and bad. Of course, I’ve never done it and never will.

*

The first printed book of the western world was the majestic Gutenberg Bible (1455), and the Bible was the most commonly printed book in the next two centuries. In the course of my reading I have also learnt other things. Among them: on average, 136 books were published every year in England in the 1570s and this number rose to 202 in the 1580s. 20 to 30 per cent of plays performed on stage went into print, and 48 per cent of those went into reprint. I am quite proud of this store of random information and occasionally drop bits of it into my class lectures. A quarto book is 6.75 x 8.5 inches in size and quartos were mostly priced cheaply (six pence). Shakespeare’s folio is, however, huge by those standards – 13 x 8 inches in height, a Renaissance coffee table book. 750 copies were printed and sold at 15 shillings without binding, and one pound sterling for a bound edition — that signals expensive and classy. Black letter type (ballads, cheap little chap books) was less prestigious than Roman (Bibles, atlases, books of law). In the case of plays no one cared to know who the author was. So title pages read something like: “Tamburlaine the Great . . . shewed upon stages in the city of London. By the Right Lord Admiral his Servants,” or, “The Troublesome Reign of King John . . . (sundry times) publicly acted by the Queen’s Majesties Players . . .”

The marks left on these ancient pages, the lazy scrawlings, the earnest underlinings, the indignant scoring out of obscenities, the Protestant reader blacking out every reference to the Virgin Mary and the saints. These books were not always rare; these relics of the past constituted someone’s present – taken for granted, scribbled on, often tossed carelessly aside when finished with . . .

To take a break from reading about eunuchs and castration practices in the sixteenth century (my latest research project) I look at drawings in the surgeon Helkiah Crooke’s Microcosmographia, A Description of the Body of Man (1615). Monster babies, midgets, moles like mountains; what looks to me like a penis sprouting giant tendrils turns out to be Crooke’s rendition of a uterus in cross-section. An elegant warrior who has ripped off his own skin (which he holds elegantly aloft) displays veins, his sinews and his musculature. “What a piece of work is a man . . . ” (William Shakespeare, Hamlet). I suddenly feel like laying my head down, placing my cheek on the giant open volume – not to fall asleep, because I am not bored, the Microcosmographia is really quite fascinating, but just to inhale the smell of the pages, to assimilate the past; make it part of me through what Crooke describes as this “organ of smellinge, we meane the Nose . . .”

*

But I actually held my first rare book many years ago. Smelled, touched and even quickly licked its covers (just to see what calf-skin tasted like). I had no accessories then, no gloves or book cradles. There was little fuss and there was none of the required degree of reverence. It happened in Bangalore, India, in the little bungalow I grew up in. It was summer vacation; I was seven years old and bored. As a special treat my father played the little music box that his family had brought from Singapore, the wood was smooth and shiny, the tune was ‘Fur Elise’. I didn’t know that then, only knew that the music tinkling through the still house filled me with a sweet-sadness I didn’t experience again until years later. “Let me show you something,” my dad announced before taking down from the top row of his bookshelf several packages wrapped in the plastic grocery bags that he wrapped just about everything in – his cassette player, his letters, his photo albums. He showed me several old books dating back to the 1700s. The Biography of John Harrington Esq. (printed: London, 1767); The Turkes Tale – A Fragment (1801) and even a first edition of Hobbes’ Leviathan – The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth (London: Andrew Crooke, 1651). My father and I squatted on the floor and admired the worn out covers. The pages smelled like centuries-old paper does and we sneezed. A few book moths fluttered around us; book lice had left their traces on several pages. The man on the cover of the Leviathan held a sword and something that looked puzzlingly like a feather duster; he loomed giant-like over a vast, rolling landscape. We admired his size, his moustache. I feared that the books would disintegrate at my touch, but my father didn’t seem overly concerned.

I learned that these family heirlooms were acquired by my grandfather who had shipped them from England to India to Singapore to Malaysia, and back to India. It appeared that he enjoyed browsing the old bookstores in London and Cambridge as a student in the 1920s, and occasionally picked up little things he could afford (most of these books are not worth much, in spite of their age). So they’d made their way across the oceans and through the years until they arrived on the over-laden bookshelves in this house in Bangalore, in the narrow bedroom with its heavy teak writing desk, the giant portrait of a solemn, bejewelled Malaysian king; and the narrow single bed my grandfather had spent his last days on looking out at our tree-filled compound. I could pretend that those yellowing pages and odd-looking typefaces transported me to the England of a bygone era. But the hold of home, the smells of incense burning before our household gods, the domestic help furiously thrashing at clothes on the washing stone in the backyard, the crows cawing raucously in the mango trees, my mother coming in and complaining about all the dust – the hold of home was too strong to allow for such transportation. India, I’ve understood even better since, does not easily let go of her own.

I rarely thought about those books after that; they came to mind only after I began my own voyages of discovery into the past. My father gave most of them to me one summer about a decade ago (the Leviathan went on a separate journey – but that’s another story) and I brought them back to university in the United States, nestled in my suitcase along with lime pickles and spicy fried snacks. I haven’t actually read the books, but sometimes, rummaging through my shelves for something else, I come upon them and wonder about the boys in the printers’ shops whose small hands carefully set the type, the forgotten booksellers who sold the printed works and the readers who bought them. But I wonder even more about the most recent purchaser of these books, my grandfather, the stern-faced bearded man I know only from photographs. P.V. Charry at the age of 20, among the first, if not the first, brown student in his Cambridge college. I wonder who he had been before he became my father’s father. What had he thought and felt as he traversed the narrow streets looking for books? Had he missed home with the sudden, sharp longing that is the travellers’ and the immigrants’? Had he been cold? Out of place? Or simply lonely? Or had his quest for antique books been too consuming to allow for mundane things like homesickness? Now, as the years go by, I also wonder about his child-bride, my grandmother, long dead now, whom he left behind in her little hometown in India. I try to imagine what she’d thought when he returned to her after nearly two decades, this husband she barely knew, now even more a stranger, with his foreign degrees and foreign ways, this man with an English accent, and with these very old books.

Litro’s mission is to find the best and most exciting new voices in fiction and non-fiction from across the globe and give them a platform for their work. Litro wants to continue to showcase the best emerging artists. You can help us by supporting our Crowdfunder Today!

About Brinda Charry

Brinda Charry is a novelist and short-story writer. She has published two novels : "The Hottest Day of the Year "(Penguin India, 2002 and Transworld UK, 2003) and "Naked in the Wind" ( Penguin India, 2007), as well as a collection of short-stories "First Love" (Harper Collins India, 2009). She has also published poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction in other forums. Her fiction has won prizes in the BBC Short Story Competition, Katha Prize Stories competitions, the Hindu-Picador Short Story Competition, and the Commonwealth Broadcasting Short Story Competition. Her second novel was awarded the India Plaza Golden Quill Award. Brinda is also a teacher and scholar of English Renaissance Literature and has published several academic articles and two academic books (" 'The Tempest' - Language and Writing," Bloomsbury, 2013 and "The Arden Guide to Renaissance Drama," Bloomsbury, 2017) and co-edited the essay collection "Emissaries in Early Modern Literature and Culture, 1500-170 ( Ashgate, 2009). She lives in Keene, New Hampshire, USA where she teaches both Renaissance Literature and Creative Writing.

What an evocative and fascinating essay. I loved the transposition between the cold but beguiling library with its treasures, and the warmth of home and family. I also loved imagining this Indian student navigating 1920s Cambridge, finding solace in the bookshops (always a good place to find solace, I think!).

The uncommon ebook society of india is the first of its kind – it’s far a virtual space for uncommon e book collectors and records buffs to read, speak, rediscover and down load misplaced books.Importantly, it targets to focus on the knowledge that there may be constantly multiple truth in history! Sourcing from virtual libraries inclusive of the net archive, google books and the net collections of numerous museums round the sector, rbsi has curated these rare books and pics, and supplied them in a context that offers them relevance and shows every piece as part of a grander entire. GST Software

Reading is a great habit and one must read books. I personally have hundreds of books. Anyways, enjoyed reading your article. Alluring Places