You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Three years ago, I took up meditation. It was for all the reasons westerners do; I wanted to look deeper into my “self,” to find better ways to deal with stress from my family and my new job, and ultimately to become a better, happier person. It’s not that navel gazing was a new subject for me; it was my enthusiasm for the self that had landed me in my current situation in the first place. My whole academic career to this point had been focused on the self. It was the subject of almost all my research as well as the nonfiction writing classes I taught four days a week. I was encouraging as a teacher, insistent that my students open up, create themselves as characters and analyze their own voices.

In my work I examined and interviewed countless scholars who had looked to their family histories, classroom experiences and emotional growth as evidence for meaningful insights and scholarly evidence. I pushed everyone around me to be courageous, sometimes with great success. Meanwhile, I was desperately trying to cater to all the powers that be with me in my own writing, to please my committee with my dissertation (I could either choose the topic I wanted or the style I wanted, not both), get my degree, adjust to a new city, pay my rent and keep my job. I was becoming hardened from starting my living and working life on an instructor’s salary in NYC and working days and nights in my office.

Although city therapy had done me a lot of good, much better than the grad school mental health center where a nice man told me my panic attacks were “in my head,” or the suicide survivor’s group where the closest survivor tried to relate to my father’s recent shotgun to the head by recounting memories of a distant cousin’s suicide ten years ago, I thought there must be another way to control my own patterns of worry and future projecting. I was tired of thinking five years ahead, trying to people please to succeed, teaching a method I believed in but wasn’t open enough to embrace and obsessing about everything. I desperately wanted to live in the moment.

Sure, over the years I had collected some Buddhist books from other professors’ house sales that I stacked on my shelf, as well as a flag or two, the material trappings of the noncommittal academic who almost by definition needs to dabble in Eastern religions. I’d also made a habit of attending myriad services with religious friends who were Unitarian, Baptist, Jewish and Episcopalian. I had friends that were Mormon and atheist and I was curious, perplexed, initially supportive, but not enough to join up. Mostly I was caught in a cycle of trying to get my life where I thought I wanted it, looking for some guidance where others found it, falling prey to the myth that this was possible but not wholeheartedly enough to adhere to anything, and ultimately realizing the fact that I wasn’t sure what the ideal was in the first place. I had checked off some important boxes lately due to my persistence. I finished my dissertation well enough and I got the tenure, but now what? My therapist had asked me one day what I wanted. It was such a weird question, like, when I got up in the morning what did I want out of my day? I had never thought about life that way. Mostly my thoughts consisted of what I needed to do, what others needed me to do, what I was supposed to do, and how to hit my marks. When I was a kid I told my parents I wanted to be an archaeologist. My father told me that was a bad idea, that I wouldn’t make any money. I remember saying I just wanted to be happy. He said happiness was not a goal. I still hadn’t learned, was it?

I have never considered myself a religious person. As a child, I was made to attend catechism classes, get baptized and confirmed, to attend church with my grandmother as often as possible and with my parents on major holidays. Religion never served a positive or meaningful function in my inner life; I thought of it mostly as an obligation to support my grandmother who I loved dearly and to tenuously hold onto a belief in God that my parents thought was important for children. My CCD teachers were the first to tell me what masturbation was (sinful and a waste of God’s gift), how heterosexual normative sex physically worked (it goes IN there?), and that confession could absolve me of my sins (although I had to fabricate sins to be forgiven for because, well, I was ten). I wore crosses more because I loved Madonna than the church, and by the time my former college roommate introduced me to friends at her house party as lost and Godless, I knew belief systems were probably not for me.

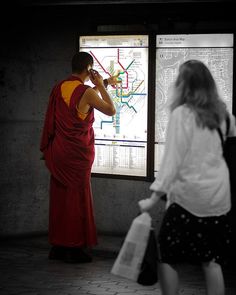

In fact, I have always been turned off by assumptions about my identity, being categorized, or being told what to do, whether in my personal or professional life. This is a real fault in NYC where people constantly want to define themselves, often by what they do least. Conversely, I truly envy others who find comfort and all that is good in faith and identification. Although I have made it this far on a fairly conservative path, I am ultimately resistant to a fault and often make problems for myself where they don’t exist. I resent others thinking they know me based on some categories I fulfill. When a popular boy I liked in middle school asked if I was going to be a cheerleader, I laughed in his face with a long awkward noooooo that only a self-conscious all-black-wearing nerd could muster. I’ve been singing since I was born but cringe at being called a choir girl. I acted for years but never had the necessary ego to consider myself an actress. I write but don’t identify as a writer. To my own detriment, I quit things out of principle or as a result of minor disagreements with the system, ultimately proving a point to no one. I have unimaginable anxiety about being called a wife after my recent nuptials. In other words, I was unwilling to trade my dislike for my Catholic upbringing for dislike of yet another set of ideas I could not completely adhere to. So it was surprising to find in a real way that I was drawn to Buddhism for its practical applications, the healing possibilities of meditation, its teachings on living a more mindful life. Unable to ever find a palatable disconnect between logical moral positives and teachings inherent in most religions and non faith based practice of these ideas possible in Christianity, I hoped to be able to extract the practical parts while leaving the faith to others.

The first time I was ever truly attracted to Buddhism happened when I took a celebratory trip to Thailand at the end of 2009 after my friend and I completed our dissertations. It had been a long and uncertain slog for both of us and when he announced his travel plans I eagerly tagged along. I had just broken up with my partner of twelve years, been forced to move out of my apartment, given my ex most of my belongings, and been distanced from friends and family who had gotten used to thinking of me as married off. It’s not surprising that some change and adventure in a tropical climate with someone I trusted had never sounded better. Perhaps because my life was at such a low point, I was immediately hooked on a feeling of calm I had never experienced before. It was my Eat, Pray, Love moment. In Thailand I was free of the life I had known since I was eighteen and mesmerized by the symbols of Buddhist religion more than those the large Catholic churches of my youth, perhaps only because they were so different from my previous experience. As intended, the oversized statues, the warm colors and the silence struck a chord with me. I felt calm, happy and warm in the hot sun and at peace in my environment. I wanted this feeling to last forever. When I got home I knew my journey of self-awareness and fulfillment would start. It was time for a new beginning.

My first meditation experiment back home took me to a Thich Nhat Hanh mindful living group that met once a week. This was perfect, practical, nonreligious and around the corner from my studio apartment in Brooklyn. I was eager to start my practice and my new path.

That first Sunday night, I walked timidly into the church basement trying to blend in but unwittingly plopping down directly next to the teacher. I didn’t know how to sit, so I awkwardly crossed my legs and hoped I didn’t look ridiculous. I bowed when others did, and tried to look down. I wanted the feeling I had in the open spaces of Wat Pho where Buddhism and meditation seemed a natural part of being. A crowd of fifty meditators later I understood that night was going to be different for me. On top of my self-consciousness, the meeting was a special tea ceremony, replete with the passing and slow silent mindful chewing of treats. Crackers upon crackers, nuts, juice and cookies got passed, sampled and passed around the hungry yet patient mouths. Growing up in a household where you could be brutally punished for making a crunching noise at the dinner table trained me to jump on the smallest lip smack with fury. I was in a personal hell: a room full of saliva, teeth grinding with no talking to mask it, thinking about being silent, mindful and not achieving any of it. Forty-five minutes of personal triumph later, it was time to meditate. I closed my eyes, eager for peace at last. The woman next to me swallowed her snot every thirty seconds for the next half an hour. My body grew more and more tense and I almost cried out after giving her mindful dirty looks. By the end and the final sharing session, which culminated in some off-key singing that made my sensitive-to-pitch ears scream, I could barely keep myself from bolting as the group politely invited me to get some Chinese food. I never returned.

After a year of recovery from this first excursion and many other trips to various Buddhist and meditation centers, one where the enlightened Brooklyn monks in training expressed passive aggressively during a meeting how they hated new people, I ended up finally settling on a small space in lower Manhattan. Daytime classes were a bit like group therapy with a higher age range of mostly female retirees. I was invited to talk about my difficulty focusing and controlling my mind and even received sympathy. When I asked my teacher for some reading, he told me not to worry about reading, just to experience. My patterns of rebellion overcame me again and I skipped the next class, frustrated, but eventually returned leaving my reliance on my library at home.

Then, bolstered by my three months of once a week success at the meditation center, I started researching silent meditation retreats, liking to throw myself full throttle into whatever new endeavor I chose. I didn’t want to spend yet another winter without some peace of mind. Running away had worked before, so it could work again. My new partner was going off to write in the cold of his Minnesota family farm and I could have stayed in NYC and kept up normal practice, but instead I decided isolation would be a quicker route to inner peace.

It was tricky and somewhat counterintuitive to try and find a retreat free from my feared trappings of religion. Yelp reviews, Trip Advisor accounts, and dated websites provided only very basic outlines of what to expect. Retreats in the states, mostly in New York and California, were thousands of dollars for silence, yoga and organic meals. If it was going to cost that much, I reasoned I could afford to fly back to Thailand. I found a place that worked with my teaching schedule and budget, $150 and my plane ticket, so I applied. According to their three-click web page, the couple running the retreat had been doing it for twenty-five years in partnership with the local Thai island monastery. Years ago, the head nun identified this couple’s potential to spread Buddhist teachings to the many curious English-speaking visitors who took a break from drinking during the tourist season to visit the monks. The pictures of hundreds of students sitting peacefully in the Thai sun were perfect. I would be joining them in January.

So I began my journey to learn the potential of intense meditation. The retreat was in the middle of the rainforest at the top of a steep mountain on a southern Thai island, known mostly for its resorts. One eighteen-hour flight, one three-hour flight, a two-hour ferry and a challenging truck ride later I made it up to the monastery on the mountain. Backpack latched on, I signed my name on a numbered sheet of white paper. I had no idea what was to come. So I slept at my seaside paradise down the mountain, had some fried rice and a beer and prepared to embark on my ten-day adventure.

The slightly graying American and Australian couple running the retreat met all forty-five of us face to face first thing the next morning. They called us up by name, asked a few perfunctory questions about where we were from and took our small donations. Some were repeat attendees, but most of the people from over twenty-five countries were there for the first time and for a host of different reasons I would not find out for ten days. It was a silent retreat. All of the normal things I did to escape what I considered real life did not apply. I didn’t know if I could follow the rules and whether this would this lead me, finally, where I wanted to go.

And there were many rules for a non-rule liking person. No phone, no technology. No speaking, no eye contact, no petting the three cute dogs that made the monastery their home. No music, no writing and no reading. No exercising outside of the forty-five minute morning stretch to a melodic prerecorded tape. There were things you could do like meditate, sleep, eat mindfully at meal times, bathe from buckets and work duty. I washed dishes after the 11am lunch.

We each got a bunk in a simple clean dormitory. I chose a mattress/meditation mat, about three feet square and two inches thick, that I placed on the wooden sleeping slats along with a small hard pillow and a mosquito net. In January, Thailand’s air is thick soup. The birds and frogs call out like car alarms in the night. I avoided the direct sun and drank plenty of water to compensate for the sweat that settled on my skin the entirety of my stay.

A typical day started with a bell at four am, sitting meditation, then our light yoga-type exercise before a breakfast consisting of fresh papaya, pineapple, peanuts, soy flakes, sesame seeds and sweetened condensed milk. There was more walking and sitting meditation and our second meal at eleven. The rest of the day was spent walking, standing or sitting in meditation until tea around four and work duty. In the evening, we’d have more meditation, and then a brief talk of about an hour from one or both of the teachers, which we listened to with great intensity.

I quickly learned that there are repercussions to this willing removal from all obligations. All you have is your thoughts and the tiny distractions of the natural world surrounding you. You are with your most essential “self.” Despite my long years of research on such things, I’d never been presented with myself in such a stark way. Initially, I became panicked. I had no outlet or escape, nothing, not even the normal restful ones where I could write and read or talk to a friend. I planned my flight in my head. I could run the next day. It would be easy; I didn’t have to stay there. I could surely find a cab to the port and just catch the next boat. I could stay in one of the beautiful resorts on the water. I had food anxiety from eating only twice a day, even if it was delicious fresh fruit and vegetarian staples. One day I burst into a kind of delirious laughter when we only had a plain white bread bun in a plastic wrapper for lunch.

The small sounds of water bottles and throat clearing that permeated the air as forty-five other people struggled the twelve hours each day made my Brooklyn adventures seem worlds away. I envied better meditation pants, stiller sitters. Tears streamed down my face during a talk or a session. Feelings of euphoria overwhelmed me in the middle of the hot afternoon. Some days, I felt like energy was going to burst forth from the top of my head like a volcanic eruption. I was doused in mosquito repellent to no avail. I noticed and envied the people who took fifteen-minute bathroom breaks just to take a walk.

On the other side of the experience, the sounds of the wind rustling through the thick leaves kept me company all day. There were moments of stillness where I lost my self and my bodily anxiety. I used the reflective exercises they gave us to redirect my emotions to the ones I loved and felt the value of the difficulty making me stronger. There were moments of learning about a “self” that I usually hid under all the layers of obligation and activity. There was nothing else to do here except face whatever was inside my head.

I realized I was not ready to go home. The teachers’ lectures at night exhilarated me as they captured the very pain and struggle I was experiencing. They encouraged us to be compassionate not just to others, but also to ourselves and made us recognize our own willingness to try something different. I slept without the aid of a noise machine for the first time in years and became able to sit hours on end through much bodily pain. I reflected on difficult relationships and situations in my life. In the three one-on-one meetings I had with our teachers over the course of the retreat, I cried over what I couldn’t control. On the message boards, provided for additional questions the teachers might aid us in answering, I was surprisingly earnest. How could I forgive someone I didn’t want to forgive? How could I deal with the pain of loss? How could I bear hard emotional and physical burdens? Why was change so overwhelmingly hard? The answers were rarely what I wanted to hear, but there was sympathy there and willing ears that reinforced that I needed to look to myself for the answers.

Then it came. I posed in the back of a group photo to prove I had been there and learned through brief conversations that the other people had struggled as much as I had. I met a young doctor from NYC who maintained every holier than thou stereotype I had left behind. I talked to two young Estonian men who were making a go of living on the island hand-to-mouth. I sat with middle-aged women who were there for their third or fourth time because they wanted to refresh their spirituality. This year was the last year they were holding the retreat – I had just made the deadline.

But I had a flight to catch. I jumped a car that took me quickly through the dense greenery to the water. I booked a hotel room in the nicest place I could find in Bangkok. I ate a seven course breakfast while I Skyped my new partner and overlooked an Olympic sized swimming pool and the Bangkok skyline. I bought trinkets and watched television and went to bed and rose late. I indulged every impulse after so much restraint.

But there were changes in me and others noticed. Back home, it was weeks before I constantly held my phone or computer. I didn’t mind the jostle on the subway for room. I really felt compassionate towards others and was happy just sitting instead of my usual constant need to being doing. The normal work stress rolled off my back. I felt good about life and wished that everyone could have the experience I just had. I was proud, although I wasn’t supposed to be. My self-imposed exile had been difficult but emotionally liberating; I had survived.

Yet, this was not a cure all. I knew no one, including me, could really take the time away from all of their responsibilities to simply spend two weeks with themselves. This fact was not lost on me. After about six weeks, I resisted my weekly practice because I didn’t have the unrealistic isolation and structure of the retreat. I wanted that perfect feeling, the warmth of the sun on my face as I raced back to Bangkok on the ferry with one of the other attendees right after we had finished. Even there, when we parted halfway, he had told me to have a “good life.” It was so final. But it was true; the excursion was not my reality. Eventually, many of my old habits came back to me: a good deal of stress and future projecting, the pressures of money and time and family and everyday life.

On the final night of the retreat, our teachers had told us we needed to separate from identification, something I had always longed to do. We should avoid defining ourselves by societal constructs and feelings of accomplishment. I understood. But they also told us to detach, to not take things personally, and to let it all, life, wash over us. That was the problem.

After the retreat I felt an impulse to write like I hadn’t felt in years. I was writing my experiences in my head, rejuvenated, excited about sharing my insights and couldn’t stop the feeling that I was going to just explode if I didn’t get it all down. I was convinced that this kind of radical deprivation of outlets was a cure all for emotional blockage. As I traveled home, I had computer and pen and paper right there as I kept writing in my head, but ultimately I chose not to record my emotion. In the past, I’d successfully kept blogs, written my daily experiences for a good-sized audience, and quickly stopped both times. Each time I realized I was living for the writing rather than writing about my living. This time, I just wanted to experience. I didn’t want to make it just another story.

So I write about it now when most of my memories have dulled in a year’s time. I don’t feel the rush of emotions, the compassion, or the excitement I felt this time last year. My writing about my experience, by necessity, is reflective rather than experiential. Reflection is a big part of meditation. Reflecting on my actions, my emotions and their consequences leads me to an understanding of where I am today. I have had the chance to see my path for better or worse. I still meditate, but cannot stick to a schedule. I relish the times at my meditation center and the feeling of just sitting with others in silence, but I often run from identification with this community, choosing to join and disappear at erratic intervals.

What this reflection has shown me most is that I like and need to identify. Writing about and studying the self is all about identification. In my writing, as I’ve taught my students over the past twelve years, I’ve had to create a self to engage my readers. Here, I’ve positioned myself as a character with a crazy family, panic attacks, anti-religious tendencies, degrees, neurosis, and a new marriage. I’m a woman who occasionally sings, acts, teaches and writes. I’m also often a recalcitrant pain in the ass. My work and writing life in many ways are at odds with everything I went to the retreat for. To get my message across, I’ve had to align myself with the very categories that have historically made me feel uncomfortable. Courting discomfort is what I encourage my students to do almost daily.

Ultimately, I can’t and don’t want to stop resisting the rules. I think it’s important to teach others to do the same. Meditation, it turns out, won’t entirely give me the answers to happiness more than anything else will. Religion may not be for me, but my foray and writing about it was not fruitless. While my “self” may be constantly evolving, it’s important to pause and make connections. It’s just another part of the difficulty and joy of having compassion for myself and for others.

About Melissa Tombro

Melissa Tombro is an Associate Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology, SUNY in NYC where she teaches writing. In addition to teaching, she volunteers for the New York Writers Coalition where she runs writing workshops for at-risk and underserved populations. She lives in Sunset Park, Brooklyn with her husband Matt and their dog Lily. Her work has appeared in Eclectica, Crack the Spine and StepAway Magazine.