You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

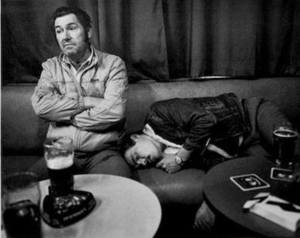

I first came across the photographs of David Wise in the Independent Magazine (24 March 1990) where they illustrated an article about drinking in Hartlepool pubs. The black and white pictures were raw and honest – brutally so – but they also depicted moments of great tenderness: a man looking at his crying girlfriend unable to comfort her, a drunken kiss, a last desperate hug before kicking out time.

I forgot about the photographs for 30 years. Then last year I was looking through a book of pictures gathered by the late Bruce Bernard. Bruce Bernard had been the picture editor at the Independent and had commissioned David Wise’s photographs in 1990. Included in the book was his portrait of a young woman in a Hartlepool pub from 1986. She is leaning back with her eyes closed, her hand on her knee with a cigarette burning between her fingers. It is a wonderful study of exhaustion.

The pub pictures had also been published in Creative Camera (“From the Bridge to the Volunteer,” September 1989) and in Photography Magazine (March 1991), but after that David Wise seemed to disappear. There is very little information about him online, and the only biographical details were in the Bruce Bernard book which recorded that David Wise was born in 1959 and died in 1999 – aged just forty.

David Wise worked within a documentary photography tradition that has represented both the “North” and the pub. There is a popular visualisation of the North that goes back to the ’30s and that was reinforced by films and TV dramas in the ’50s and ’60s. It is of an industrial landscape and tight-knit communities and families. The North is seen as a different country – a bit like the Wild West – ungentrified, where the men and women work hard physical jobs in pits, factories, and docks.

The North has been widely depicted by photographers, whether it is outsiders such as Humphrey Spender or John Bulmer or photographers from the North such as Shirley Baker, Tish Murtha, Chris Killip, and Graham Smith. They have provided an “authentic” picture of working-class life in the North over the last 60 years, capturing in unflinching detail the effects of economic change and industrial decline. But they have also recorded the humour, tenacity, and strong bonds that continue to hold the communities together.

The pub features regularly in depictions of the North. It is a natural subject for social documentary photographers – pubs are full of big characters, unexpected action (sometimes violent), and fraught human relationships. Booze tears away people’s reserve, exposing their most extreme emotions. It is Graham Smith’s pictures of pubs in Middlesbrough that seem to be the greatest influence on David Wise – though both artists also owe a debt to Bill Brandt’s photographs of East End pubs in the thirties.

The other photographer who was an influence was Anders Petersen. His acclaimed book Café Lehmitz recorded a lowlife bar in Hamburg and his photographs have the same intensity and capture the same desperation to have a good time that we find in the pictures of David Wise.

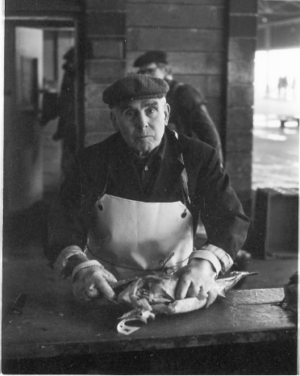

David Wise photographed his hometown of Hartlepool. Hartlepool suffered greatly from the loss of heavy industry – first shipbuilding then steelmaking. In the ’80s it had an unemployment rate of 30 percent, and those men who were employed worked in hard physical jobs such as fishing and oil rig construction. Hartlepool suffered all the problems that have blighted former industrial towns in the North – unemployment, high crime, urban decay, drug taking, and alcoholism. Even amongst other northern cities, it has a reputation for being a hard place. John Bulmer produced a harrowing series of photographs of Hartlepool in the harsh winter of 1962–63, and the same proud, haggard faces can be seen in David Wise’s pictures thirty years later.

David Wise’s particular setting was the old port area of Hartlepool known as the Headland. In pubs such as the North Eastern, the Middlesbrough Tavern, and the Volunteer, he photographed men and women determined to get drunk and escape their environment.

David Wise must have earned the trust of those he photographed. This is an area where everyone knows everyone, and photographing in pubs is an intrusive activity. If a stranger tried taking pictures in these pubs, he would end up getting his camera smashed. David Wise has said that, “Photography is associated with voyeurism. But these are pictures of my life taken with full assent, so I don’t believe I have a charge to answer.”

The men and women depicted are strong but battered, protective of their independence. Their aim is to get drunk, to enjoy themselves, and to escape their problems. They are photographed at closing time when drink has taken its toll and their heads are bowed in an exhaustion that can look like despair. These are intimate portraits and the subjects are presented with compassion.

In the Independent article, Graham Coster said the word “hard” is on everyone’s lips – hard jobs, hard times, hard women, hard drinking. He says that hard means “difficult, intense, determined, proud, emboldened, and often pitiless.” These are the very qualities that David Wise captures in his photographs. They are not polemical. David Wise is not reaching to make some political point about poverty or social deprivation. He is just presenting the world around him as he found it.

After publication of the pub pictures, David Wise disappeared from the photography scene. There is no record of any exhibitions of his work, his pictures do not come up at auction, and his work is absent from the surveys of British photography of the ’80s or ’90s. Were the pub photographs just a one-off thing? A lucky coming together of photographer and subject?

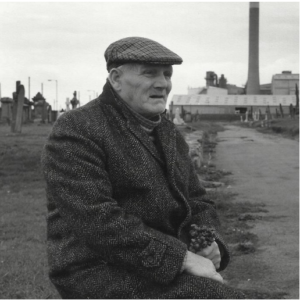

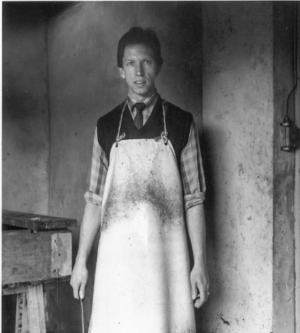

Hartlepool Museums Service hold a collection of David Wise photographs that were donated by him before he died. The collection is not catalogued, but a few of the images are included on the Hartlepool History Then and Now website (www.hhtandn.org). These portraits of Hartlepool men speak of the dignity of skilled, physical work – of jobs that have now disappeared – and of male camaraderie and sometimes loneliness.

There is also reference online to a book by David Wise called Gravity and Grace: Boxing Culture in Hartlepool, which was published by Hartlepool Borough Council in 1992 but which now seems to be unobtainable.

Biographical details about David Wise remain elusive. A brief biographical note in the ’90s said he was self-taught and that he had worked for a while as an unemployment benefit officer. Although he was regularly commissioned by Hartlepool Borough Council to take photographs, he does not seem to have been a professional photographer.

The history of photography includes several individuals like David Wise. People who take a brilliant series of photographs of a particular subject, get those pictures published to some acclaim, and then disappear. It often takes someone with a discerning eye like Bruce Bernard to recognise such talent and bring it to public attention. It would be a pity if David Wise were forgotten. His pictures of Hartlepool pubs are amongst the most moving images of working-class pub culture we have. He also took tender, powerful, humane photographs of other subjects and captured the dignity of men working in punishing, physical jobs.

David Wise said, “My pictures are inevitably personal, in describing life I describe myself.” He wanted his photographs to work like poems, and he succeeded. When you look at his work, you see the human spirit standing against adversity, in anger and resignation, and with a determination to squeeze moments of pleasure from a lifetime of grind. His photographs deserve a wider audience, and he should be recognised as an important contributor to British social documentary photography at the end of the last century.

All reasonable efforts have been made to trace the copyright holders of the images used in this article.

About David Ford

David Ford lives in London. A collection of his poem has been published by Happenstance Press and his short story 'Last Great Blizzard' was published in Litro 131. He is currently researching the work of the photographer Henry Grant.