You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

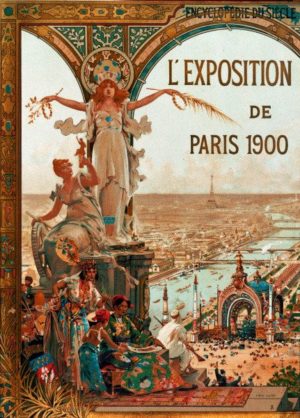

World’s Fair, Paris, summer of 1900: we’ve arrived from two dozen countries. Nine hundred ninety-nine women with a single fever dream. In a mixture of addled French and our languages, we talk while heading down to Vieux Paris, to the Victor Hugo display. Religion and violence intertwined. A wash of jugglers and clowns and madmen: fiction made real. Esmerelda dances beside her funny white-haired goat. Quasimodo – a sheer shadow in his warped tower – gazes down. Food vendors dressed in medieval costumes sell mead and meat pies, shouting out good deal with outstretched hands. The smells leave us nauseous, a slick, hard feeling, but still we buy pies and bite in. Small packages warm us. Sour acid crumbles down our throats.

Nervous to meet? Yes, but more nervous not to. But what if we start arguing? Grow bored with one another; hateful, even? If we meet, for a few days, then scatter?

We must, as best we can, distract ourselves. Here, a moving sidewalk shoots us to the Trocadero, past skulls leering at the Dahomey hut, over the Jena Bridge. Here: exhibits chart the glories of progress: colonial riches, a sparkling (overdone) American-style Ferris wheel.

We stay for hours, gathered in small groups, chatting. Some link arms. Some stay silent; others shout, amid shimmering lights at the Palace of Electricity. This landscape’s composed entirely of flashes, threaded through with novelty.

*

The next morning, Frau Elena, the one who’d called us, takes the podium, birdlike, Eiffel Tower gleaming at her back: hands at her heart, mouth working reedily. “The year: nineteen hundred. Propitious, yes? The year we wash our hands clean. The year we’ll use to imagine.”

Clustered in a circled pack, we listen, empty-handed, and dream.

Around us, the sounds of an entire World’s Fair coalesce: flickering lights, tinny music rising up from birches, turnstiles, bowled sky. Gripping the podium, Frau Elena releases her skirts and starts speaking, head tilted, voice a bullhorn, detailing the history of this place. “Earlier this year, Parisian architects received free rein to design buildings in any style. They planned to gut the city completely, leaving only Trocadero and the Eiffel Tower untouched.

“Soon,” she continues, “complaints poured in about inadequate space. The Japanese delegation lacked room on the pavilion. The U.S. – kept from the Quai des Nations with the other first-world powers – launched an official protest.[1] We are equally if not more important: their argument. Laughable? Maybe. But in the end, their bullishness won out. As they squeezed between Austria and Turkey, all the ‘less important’ countries made room.”

Yet the pavilion needed a centerpiece. A signature. A clou. Transforming the Eiffel Tower would do it, the higher-ups said. Change the lower half into a waterfall; crown the upper with a 450-foot statue of a woman with searchlight eyes blinding everyone in her reach: a brilliant panorama, sharp-lit gaze crazing the roving tourists. Or crown the tower with clocks, sphinxes, celestial globes: everyone spouted out madhouse dreams.

“In the end,” Frau Elena says – spinning to us, triumphant, black braids unwound, long dress hiked to her calves – “the Committee chose to apply a coat of golden yellow paint to the Tower’s spike, then turned their attention to more reasonable alternatives.”

And us? Before we can move forward, we must decide to collaborate. It’s not as simple as it appears. Perhaps, she warns – reedy voice grown severe – we’ll start catfighting, quibbling before our three days are done. In such circumstances, who’d build a fresh community? Who’d want to? Not her. She’d never want to leave with such a crew.

And so: in a nervous haze, we spend three days among the lights, among Swedish castles and Turkish turrets that stir every longing we’ve ever known. Seventy-two hours; more like a hundred years. Among pleasure gondolas, fishing boats, Art Nouveau architecture, we wander, splashily clean. Our voices din among the torrent. Cakes and sticky breads linger in our throats.

Every few hours, Frau Elena comes round: small-faced, back so elegant, she could bear wings. In groups of two dozen, we head off to inspect the diesel engines, the talking films, even that magnetic audio recorder (the telegraphone, a mustached man at the front proclaims). We try to pretend we’re engaged, not struggling to decide whether we could live together, as one community, for weeks, months – years? Inspecting the first matryoshka, Russian dolls nested in dolls nested in bellies, we find the smallest, only fingernail size. Clustered together, claustrophobic, we travel to the pavilion Gates of Hell. The door’s bronze and plaster; massive. For a whole year I lived with Dante, with him alone: Rodin’s scribbled words. At the end of this year, I realized that while my drawing rendered my vision of Dante, they had become too remote from reality. So, I started all over again, working from nature, with my models.[2]

A triumph: six meters high. Beneath its portal, we loosen our lips.

“What,” we ask one another, “do you most love? What do you most want to leave?”

Soon, our laughter rings from every turnstile, every beacon. We joke with abandon, in basic French, with endless gesturing. We get along. We would get along, in hills or mountains, among the crystalline slopes of whatever forests we’d find ourselves in. The hope of it threads through our throats. Our hearts lunge forward. We’ve agreed, without even needing to speak.

Soon enough, our question changes: Where could we travel and not be seen? Beijing, Buenos Aires? Impossible, crowded spots. Some wooded valley: fairy houses, piled-up sticks? Or a Paris suburb? The Bois de Boulogne, say? Nearly a thousand women sailing about its glimmering lake? Consider its a rich history: a remnant of the ancient oak forest of Rouvray – now the forests of Montmorency, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Chaville, and Meudon—

“A simple forest?” one woman laughs, showing horse-like teeth. “Ridiculous.”

“What’s wrong with a forest?” The chant rises up. “Leaves, mushrooms, sweet reek.”

“We need a space far more beautiful.”

We must not be found; that much is certain. If so, our society would be ended posthaste. We’d be laughed out of town; told to forget every notion we’d ever had of pure music, or of bodily purity. Pariahs, we’d be: no longer attended to, no longer the darlings of our respective stages; no longer feted, given trophies, no longer (we fear) even loved.

We back up, talk through the plan: a society of pure music, the first of its kind, untrammeled by spiritual deadness. Unruined by critique. Heart-rich, in a land meant for us. One where we’d lash together, sticks for a boat. Where we’d birth the first female sound.

“It’s been done before,” one girl says (too thin, with a downcast look).

“Not like this,” we answer, sharp-tongued. “Not so well.”

Thrilled, we start chattering, recalling operatic music: the rising tones of magma, geyser-spray, tectonic plates shifting underneath. In our ears rings the tone-poem of Jean Sibelius. We’ve seen the score: Finlandia. Only seven and a half to nine minutes long, it masqueraded (to avoid Russian censorship), under various titles: Happy feelings at the awakening of Finnish spring. A Scandinavian Choral March.

We won’t masquerade: we’ll become ourselves, better than any utopia.

Briefly, over lunch, then walks, then dinner, we review the historical attempts. Take the Oneida community in New York: seeking heaven on earth, or harmony, living as a single family. A noble enough goal, we assume. For a full day, we study their books, examine the photographs of their 93,000-square-foot home, The Mansion House.

“Take this as inspiration,” one girl shouts, enthralled.

“Don’t forget the general meetings,” another answers, sour-tongued. “Each community member criticized, their moral value considered. Faults aired. Listen to their goal: eliminate all undesirable character traits. And from their records: Mr. Noyes summed up. He said that Charles had some serious faults; that he had watched him with some care; and that he thought the young man was earnestly trying to cure himself.[3]”

“Here,” another girl, Lina, shouts, clutching a dog-eared page, “Women over forty required to act as sexual mentors for adolescent boys. Not allowed to conceive or bring trouble.”

We sigh, imagine pleasure without the decades-long aftermath. Ruddy-cheeked, bare-breasted, statuesque women, teaching lick and fist and chest out of duty, begging themselves not to fall in love. Press of lips to spine, hip to hipbone.

“But look,” a younger woman, Myra, calls, pushing back jet-black bangs, fumbling to the book’s end. “They have vineyards by the acre, raspberries, strawberries. Ten or twenty acres. Pear and apple orchards. Barns filled with sheep and pigs. Stabling for over one hundred horses and cattle. A truly natural spot, it sounds like. Perfection, I’d say.”

Still we sneer, reading over her shoulder: “In whoredom, love is paid for by the job.”[4]

Up until now, we remember, we’d always been trustworthy. The men in our lives liked us that way. They bound us, buried us, cared for us like little ferns; called us, once in a while, beautiful. The sound of beautiful became us, signaling that, temporarily, we had worth. We breathed in beauty as the Graces had, distilled it from our fingers’ motion, the cross of our legs, even the downswing of our bones. Dead – so we’d be in less than a century. All of us. Faces like fresh-plucked poppies, we could hardly believe it. For a while, men convinced us it was not so.

Until now, we’ve had only inklings of revolution. Our inspiration arose from the innovators of old: Maurice Ravel, who filled his house with tiny musical toys, convinced mechanical things contained musical souls. A small man, tending a tiny garden in a house meant for an oversized doll. Anton Bruckner, obsessed with counting: windows, statues, prayers, leaves. Before composing a piece, he counted the exact number of bars he’d need, refused to sway from that count. And that Erik Satie, demanding a piece be repeated 840 times in performance. Once attempted, the feat took over eighteen hours.

Or, our greatest love: Olivier Messiaen, who demanded that trombonists render a passage more green-orange. For him, each note birthed a color, and those colors shifted; orange to purple to navy blue. Swapped brain connections linked color and music. An obsessive transcriber of birdsong, he composed Oiseaux exotiques in 1956, involving eighteen different species from India, China, Malaysia, and the Americas. Such a collection could never exist in nature, he’d proclaimed. Only he could marry them, bring together divorced nature and sound.

We played music first because we were taught to. But once we found the love for it, we never let that love release. Music let our minds slush and fill with ocean surges, with March skies smacking continuously of snow. We loved music the way we imagined girls love cigarettes, the slim paper weight faltering. At first, we were only clever, so our teachers had said. We flinched when aggressive notes found us. They cleared, and our muscles slacked.

Over time, our technical skills improved. Music became an internal thing; a need. We tapped at the dinner table, sung notes under breath, drove mothers and sisters mad. We no longer whispered bass and treble. We proclaimed. Notes became our alphabets. In feathered fields, the weather grew dreary. Our mountains mulled frost. Still, we turned the pages of Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Brucker, Satie, Brahms. We honed our use of metronomes. We played.

And now, in Paris, we gather together and decide: we’ll move to a grand stretch of water, an oceanic tilt. We pull out maps and scan through every coast. Thunderous waves will become neighbors. We’ll found our society on the shores of somewhere. On shifting dunes.

*

Watergate Bay, Newquay. Cliffs and caves. Two miles of golden sand. Reliable surf from the Atlantic swells. Wheeling overhead: peregrine falcons, fulmars, gulls. Everywhere, birdsong, thrilling and strange, pooling from open beaks. We imagine that syrinx, the two-sided organ allowing vocal gymnastics, producing two pitches, unrelated, at once. That wood thrush, Hylocichla mustelina: what a genius, performing rising and falling notes simultaneously.

If you hear a bird sing, our teachers once told us, it’s probably male. In temperate zones, females tend toward shorter, simpler calls. Males produce the complex sounds we interpret as song. Young birds, fledgling, recreate their tutors’ vocalizations till they’re perfectly matched. Songbirds – catbirds, thrashers, mockingbirds – mimic otherness: cats, frogs, fire alarms.

Cornwall: Frau Elena’s birthplace, not far from Paris. A spot of birth and rebirth, of invention. A place we can breathe. If absolute music could arise from anywhere, it’s here.

All around: the hint of new music. Buzzing bee-like in elbows, stirring waists and spines. We’ve become one band, one pack. At shore’s edge, we listen to the waves’ sway and swell, flushing off Paris and men’s warnings – you’ll fall ill, catch pneumonia, starve. Not for now. We remind ourselves: we’re thriving, hungry, well.

We wake off this coast, a band of childless, motherless girls, our skin tones ranging – tawny-skinned, ceramic, skin as dark as water before stars. Dressed in loose skirts and shirts the color of autumn, we’re filled with the hope of wheat fields before they’re plowed.

We’ve arrived, the nine hundred ninety-nine, toting whatever instruments we can: flutes, violins, pianos, organs, violas: every symphonic object, every talisman. We heaved them onto the shores with mahogany thumps, metallic clangs. We remember our histories with these old companions (we touched their keys, blew into them our breath, offered our labors, the way men lifted firewood to flames). Years of hours, spent in motion even deaf men could feel. Jubilant – arms linked, faces skyward – we remind ourselves: we’re done with all that.

To invent a new music, we must first forget the old.

Waking, we imagine ourselves afloat in the Dead Sea, lighter than water, than air. Not wheat and chaff, as nature intended. Whale-bellied, dolphin-thin, straight-spined, hunched: no matter. Thrilled at the novelty, we dive headfirst into waves, hoping they’ve got what we’re missing. Uncontained, an intensity rises in us: the energy of fish bones, marrow, mud.

At shore edge, starry-eyed, we invent dances, give speeches absurd in historical reach.

“See,”a girl of nineteen shouts, jumping from a jutting rock: “Adam made from the rib of Eve, nicked from her body.”

And, “look here,” another calls – twenty-three, head held high as she mimics sheer greed – “Eve eating freely of the garden’s trees. Slaking hunger because it would otherwise have consumed her. Embracing the rumbling in her gut.”

“And here,” a third woman says, with a sallying dance, blond hair flinging, “Eve describing her first waking morning, sensing nothing inside her body but air (and God, of course). Every momentary motion, fish and fowl, upended, veins and tendons blossoming.”

Strange dreams fill us, nothing like the blurs we’d had in our family houses (small fires being set, flaming out). No: we dream of Robert Schumann, Romantic, face golden with suffering. My heart pounds sickeningly, and I turn pale: age eighteen. A year later: My symphonies would have reached Opus 100 if I had but written them down. Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible.

So full of music. We connect with his two sides: Florestan: the passionate, energetic aspect. Eusebius: the melancholy, introspective one.

Swayed, we strip. We’ll be embodied, visible. Ourselves, no poor imitations. We enter the sea. Cold waves scar. A startling feeling: we’ve hidden behind layers for months, years? The new-song urge stirs in us. Rushing out, we dress and begin.

How to find the first note? Authentic sound would resemble what? If only we had a compass, a map. On the beach, we set instruments in cases, lift them in a simultaneous rise.

“Start with the first notes you remember playing,” one girl cries, bow at the ready, and tries a careful scale: one octave, two. “The note that first rose up when you touched keys.”

In summer’s sheer humidity, her notes squawk, refuse lift-off. We all have a different notion of sound. Our pianos’ tones shifted based on altitude, sea level to Argentinian salt planes. One gave a concert in the Himalayas – mirrored music, five thousand meters high – altitude turning the notes crisp, her fingers freezing, mind refusing to recant.

“Swim first,” Frau Elena shouts. “Afterward, try again.”

Nodding, disappointed, we dive, resurface. Algae winds around ankles. Saltwater laces teeth. Breath jitters deep down. The air reeks of metallic mud. Each face pressed against the next.

We’ve listened long enough to stories of our sickness: thorns and strains, deathly hallows, that old urgency to drown, to sacrifice. No longer will our bodies anchor to bone. We’ll leave the poor musculature of tendons and flesh, turn eternal, airy, through the very fact of song.

At least that’s the promise we bind ourselves to, each to each. Refusing stale myths, recorded words, we dredge up every underhanded consonant and vowel.

Here, we trace alphabets in sand, creating tiny pockets and rivulets. Hours pass. We feel like children; not timebound, in flux. Against the backdrop of our wooden and wind instruments, against fluttering pages, we stand and dance: feet to face, hand to arm, wrist to femur, ulnar to nerve. Every overuse injury we flag and pressure, releasing strain.

Soon, our dampened scores look useless, ink-scribbled sheets. What purpose do they serve? What value, other than reminding us what we’ve left?

In one line of nine hundred ninety-nine, we stand, pages clutched to chests. Against the sea air, they crackle: delicate, out of place. For a second, the fury of past decades fills us. For too long, we’d believed notes could save us. We’d relied on notes – an empty hope – alone.

“Toss them in,” one of us shouts – the youngest, a thin, piping voice – and the rest of us follow, shivering. Pages lift, a single blinding force; starlings, taking flight. A single breath holds us, overwhelms. Among strawberry anemones, among crabs and rock pools, those pages descend, then sink. Good riddance, yet our minds whirl with nostalgia. A fold, a ripple.

Blue-green water eats those pages up. And then: the eagerness we once felt to fill stages, hold fermatas, leaves us. Our dreams grow grassy. The staffs that predict our present disappear.

[1] https://www.arthurchandler.com/paris-1900-exposition

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gates_of_Hell

[3] https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/religious/the-oneida-community-1848-1880-a-utopian-community/

[4] https://library.syr.edu/digital/collections/h/Hand-bookOfTheOneidaCommunity/