You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping She left the photograph on the table. She knows this, because before she left her apartment this morning she turned, looked at it, and said, as usual: Auf Wiedersehen, meinen Schatz. She walked out onto Sebastian Strasse and pulled the collar of her coat up, like his in the photograph. She smiled at this, wondering whether he too, on the other side of the Wall, pulled his collar up against the chill and thought of her. She stopped to look at the Wall at the end of the street, grey as the sky above. Perhaps he too looks at the Wall. He told her, when he visited, that the Western side was covered in art; he had described the section he walked along every day on his way to work: the colours, the faces, the words. She imagined him stopping to admire something new, and tilted her head, trying to conjure a better view of him in her mind. A noise, boots on concrete, distracted her. She turned. A man in a black overcoat nodded at her. She smiled at him, moved her gaze to the pavement, and walked in the opposite direction. She carried on with her day: right at the top of the street, left, then right again, the door to her office, typing, a new paper cut, making her boss’s coffee, apologising for her spelling errors, throwing her coat on, a quick visit to the grocery store, home.

She left the photograph on the table. She knows this, because before she left her apartment this morning she turned, looked at it, and said, as usual: Auf Wiedersehen, meinen Schatz. She walked out onto Sebastian Strasse and pulled the collar of her coat up, like his in the photograph. She smiled at this, wondering whether he too, on the other side of the Wall, pulled his collar up against the chill and thought of her. She stopped to look at the Wall at the end of the street, grey as the sky above. Perhaps he too looks at the Wall. He told her, when he visited, that the Western side was covered in art; he had described the section he walked along every day on his way to work: the colours, the faces, the words. She imagined him stopping to admire something new, and tilted her head, trying to conjure a better view of him in her mind. A noise, boots on concrete, distracted her. She turned. A man in a black overcoat nodded at her. She smiled at him, moved her gaze to the pavement, and walked in the opposite direction. She carried on with her day: right at the top of the street, left, then right again, the door to her office, typing, a new paper cut, making her boss’s coffee, apologising for her spelling errors, throwing her coat on, a quick visit to the grocery store, home.

Now she walks into her apartment, shakes the cold air from her limbs, flicks on the light, puts her handbag and bag of groceries on the floor and her keys on their hook. She pulls off her gloves, unzips her coat, unravels her scarf, and looks in the direction of the photograph. Her lips begin to form the words she always says at this point of her day, Guten Abend, meinen Schatz, but she does not say them. The photograph is not on the table.

She steps forwards, knocking over the bag of groceries in the process. The milk bottle clinks against the floorboards, and a slow trickle of milk seeps into the carpet. The photograph has been on the table ever since it was taken. Ever since he visited here, carried over on a rare train from the West. He appeared in Friedrichstraße Station in his western clothes: Levis, white shirt, denim jacket slung over his right arm. She had kissed that man with Brylcreem in his hair under the watchful eye of the border guards.

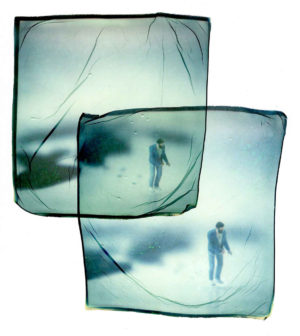

She had him in her hands for twenty-four hours. When they arrived at her apartment, he picked up her camera and proceeded to snap her on their limited travels: as she walked along streets, slightly ahead of him, eyes flitting left to right, in the manner of a bodyguard protecting their charge. They developed the photographs in the makeshift darkroom they created in her bathroom. To this day she still does not know how he got hold of the materials required, but she does know he disappeared for about an hour despite her protestations about the danger. He left his denim jacket strewn across her bed. She sat with the material pressed to her nose, trying to get the measure of all the components of his scent, as if she might be able to concoct it herself when he had crossed the border again. When the photographs of her came into view, she instantly hated them all: her head always turned towards him, her ugly brown coat, the dimples in her cheeks, but he demanded she sign one for him. A love note he would carry from East to West if the border guards did not confiscate it on the way.

She walks to the table and rubs her hands over it as if it might have developed a mouth and swallowed the photograph whole. Then she crouches down and crawls under the table, feeling in the shadows for the edges of the frame. She finds a corner of a carpet tile and pulls it up, and then another and another. She stops herself, and cannot decide whether to laugh or cry. After all, how could the photograph have fallen from the table and crawled under the flooring?

He would laugh if he could see her now. She can hear his laughter as if he were stood in the doorway of the apartment, and she turns to check whether he is actually there. A moment exists in which her heart beats too quick for her ribs and she fears it might break free, but the empty space thwarts its excitement. Crazy, he would call her. He called her that before he walked through the checkpoint at Fredrichstraße, when she clung to his denim jacket, afraid of never seeing him again, of him finding a nice Western girl who he could kiss without having his person thoroughly examined.

Perhaps she didn’t look at the photograph before she left the apartment, not on this table at least. Perhaps it was on the bedside table, and it was the bedroom doorway she stood in. She shakes her head. Crazy, yes. She walks into the bedroom, flicks on the light, and looks towards the bedside table. A lamp. A book. A half-filled glass of water with a lipstick stain. Is the lipstick stain hers? She walks towards the glass, and picks it up. Did she forget to take her lipstick off last night? She mentally retraces her steps from yesterday evening: got home; keys on hook; coat, scarf, and gloves off; Guten Abend, meinen Schatz; dinner at the table with the photograph; television for an hour; make-up off – a tissue rubbed vigorously against her lips because she was wearing a shade of pink she hadn’t before and it was proving impenetrable; tissue scrunched up and thrown in the bin; scrubbed face in bathroom until her natural pallor reappeared. She examines the bin’s contents. Tissues for every day of the week, and yesterday’s on top with its different hue, but then the lipstick on the glass. She pinches herself. Crazy, yes. She mustn’t have scrubbed hard enough. A stupid detail to distract herself with when she needs to find the photograph. She looks at her bedside table once more: glass, lamp, book. No photograph. She tears the bedsheets from the bed, the pillowcases from their pillows. Nothing.

She definitely looked at it before she left this morning. She went from bedroom to hallway, looked back at the dining table, and smiled. She walks. Four steps to bedroom door. Eight steps to apartment door. A brief turn of the head so the dining table lies in her line of vision. A smile she doesn’t really feel at an empty space that wasn’t empty this morning. Did she linger a moment longer this morning? Yes, so it wasn’t a brief turn of the head. It was a full turn of her body towards the photograph, and she had her keys in her hand. She picks up her keys now, and grips them so tightly that they leave their teeth marks on her palm. She stares at the spot where she left the photograph, wills the frame into existence. Why did she linger longer this morning? She jangles the keys, lets them hit her fingers, as she recalls the reason: one year since he visited. One year since the photograph was taken. She knows this for certain because he scrawled the date on the back of the photograph, and she had looked at it only last night. There was a message on the back which she examined from time to time. Promises and kisses. A declaration of love. A signature and a date as if it were a legally binding document.

So the photograph was definitely on the table when she left for work this morning. Did she go back, one more time, before she left? No, but today she did sit at the table and eat her breakfast, instead of leaning against the kitchen counter, so she could enjoy the company the photograph evoked. Toast. Coffee. His face. A smile with a gap in it; a lower incisor was knocked out in a fight he refused to talk about in any great detail. His hair slicked back. His Hollywood style, that’s what he called it. She preferred his hair ruffled, and had tried to muss it up before the photograph had been taken, but he refused, holding her at arm’s length. Now take the shot, he said. Standing, smiling, branches dancing behind him, the collar of his denim jacket turned up and a cigarette gripping at his upturned mouth for dear life. A puff of smoke gave him an ethereal quality. She didn’t know if she liked it at the time, when the photograph developed and the real thing stood by her side, but the more she dwelled on it during lonely mornings and over meals for one in the evenings, she changed her mind.

The low rumble of a U-Bahn train beneath her feet makes her look down, makes her question whether the photograph could be under the table. Perhaps it did fall, and she didn’t feel it the first time around. But the trains have been moving in the ground beneath her apartment building ever since she moved in, and long before that, and nothing has ever fallen, slipped, tumbled because of them. Still, she walks back to the table, wishes she could rip the light from the ceiling to illuminate the spaces she might have missed during her first investigation, but scolds herself. The table is an average-sized table for two people, three at a squeeze, not something from a royal court. She did not miss the frame the first time around; the frame is not on the table nor under the table. She looks to the sofa, the television, but knows the photograph will not be there, because she left it on the table. She turned to look at it before she left for work.

Or did she? Is she getting confused with yesterday’s routine? Did this morning somehow differ because it’s an anniversary, one year since the photograph was taken? Maybe she carried the frame around the apartment while she cleaned her teeth, because she refuses to stand on the spot when performing this ablution. Crazy, he called her when he observed her, white foam at her mouth, wandering around. She had thrown the frame at him then; she meant it as a joke but it nearly hit him in the face, and he tore the toothbrush from her mouth and cut her lip in the process. A row ensued. A row in which she picked up the frame again, and threw it at the wall. The result was a chip in its top left-hand corner. She often spent time rubbing that little nick as if trying to buff it out. The row was over before it began, as was his furlough into the East.

She opens the cupboards in the bathroom, lifts the mat, lifts the toilet seat, lifts the cistern cover. She lies on the floor and peers beneath the bath. No photograph. No frame. Just a bruise forming on her elbow from where she bashed it against the tiles. She sits on the floor, leaning against the tub, with her head in her hands. She can’t remember if she really did leave the photograph on the table, or if she moved it somewhere else. Maybe she took it out of the apartment. Crazy, she whispers. But nevertheless she goes to the hallway, and empties the contents of her handbag onto the floor. Purse. Powder compact. Lipstick. Cigarettes. Tissues. Nothing else.

She opens her powder compact and examines her face in the tiny mirror. She stares at her reflection as if she expects it to suddenly break into laughter and tell her where the photograph stands. She tries to decipher a code in her facial expressions, but snaps the compact shut. Crazy, she calls herself.

She puts the compact back in her handbag along with the other objects she poured onto the floor. She pushes the long-abandoned grocery bag so it leans against the wall, and uses a tissue to mop up the puddle of milk. Did she do something similar to the photograph? Obviously she didn’t mop it up, but did she hide it away?

She opens drawers in the sideboard, scattering newspaper clippings and documents onto the floor. But she knows she did not hide it away. Why would she? She stops herself, clutching a newspaper from the day he arrived to her chest, and looks from left to right. She sniffs the air as if her apartment were not her own; she does not know why she does this. The air undeniably smells of her: her perfume, weakly masking the perspiration provoked by her racing heart, and the sweet stench of the spilt milk.

She walks towards the table, rubs each of its imperfections, focusing on the spot where the photograph stood. Auf Wiedersehen, meinen Schatz. Her mind mimics the slamming of the door. She looks at the door, at the peephole, half-expects an eye glaring back at her, and jumps when there isn’t one. Did the Hausmeister let himself in? Did he carry out some work on the apartment? Did he move the photograph? Is the table out of place? Did she complain about cracks in the ceiling or stains on the carpet? He usually tells her if he plans on visiting. He usually visits on weekends, when he isn’t in work, and she usually makes him coffee and engages in idle conversation with him while he hammers and chisels and wipes his hands on his patched-up overalls. And he, without fail, returns everything back to its place. He often tells her about his photographic memory, demonstrating by memorising paragraphs of newspaper articles and reciting them back to her as she marvels at his talent.

She walks around the room, looking for wet paint. She runs her fingers along the walls, checks her hands for smears. Nothing. She opens and closes the kitchen door; it still squeaks. She has been meaning to tell the Hausmeister about the fault for a few weeks. She looks at the table as if the photograph might somehow be back in its place. She catches her finger in the door, and cries out. A trickle of blood runs down her palm. She rushes to the sink, turns the tap on, and winces as the cold water hits her broken skin.

She switches the tap off, picks up a dish towel, and wraps it around her hand. If he could see her now, he would call her crazy. He would call her crazy for opening and closing kitchen doors. He would call her crazy for senseless multitasking. He would call her crazy and kiss her bloody finger. She turns, and leans against the kitchen counter. Her eyes come to rest on the counter opposite: on the photograph, which stands next to a piece of toast on a plate and a cup of coffee marked with a lipstick stain that isn’t her shade of pink. She ate her breakfast this morning, didn’t she? She definitely ate her breakfast, sat at the table with his photograph. And his photograph was definitely on the table when she left the apartment that morning, because she whispered as she does every morning: Auf Wiedersehen, meinen Schatz. She sniffs the air again, hoping to smell paint or oil, hoping to smell the Hausmeister’s tobacco, or even him: him with the denim jacket slung over his arm, him with the gap-toothed smile he won’t talk about. Perhaps he climbed over, ducked and dived to get to her. Perhaps he will leap out from behind the kitchen door. She walks to the door, pulls it towards her, and stares at the empty space. Crazy. She presses the heels of her hands into her temples as if she might rip her head in two. If someone were watching they would laugh and call her crazy.

About Emma Venables

Emma Venables completed her PhD in Creative Writing at Royal Holloway, University of London. She is currently seeking representation for her first novel, which explores the experiences of German women in Nazi Germany. Her work has previously featured in The Gull.