You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

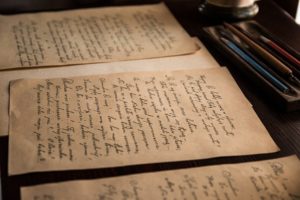

17th September, 1955

My love,

The house isn’t half empty without you. I came back this evening from Walmsley’s, it wasn’t even half-past six, and when Mrs Pemberton was standing on her doorstep, she smiled at me and asked how you were. I’d almost forgotten you’d gone to Keighley – like I’d almost forgotten I’d married a Yorkshire lass! – but then I remembered, and it didn’t half make me sad to tell her. You’ll be back soon, I know, but it doesn’t mean I don’t miss you every day you’re gone.

It was a bit of a difficult day at work, my love. My one and only. They rag me on a bit the lads. I don’t know why, I’m no different from them, but for some reason they’ve got it into their heads I’m a bit of an oddball. It’s a small place as well, so it’s not as if I’ve a chance to make many friends, but every time I feel down and start regretting that I left Courtauld’s, your face comes to mind and it all seems worthwhile. You’ve no idea how much I think about you each day, petal. Wish I’d never let you go off to the White Rose – it’s here you belong, now, on this side of the border! Mr Crowther was saying this only just the other day; I was in his shop, trying to decide what to get for tomorrow’s meal, and he asked me out of the blue where you were, as he hadn’t seen you for quite a while. When I told him what had happened he seemed quite sad, but I said it wouldn’t be long before you were back. And it won’t be, either.

I’ve been trying to get rid of that stain you talked about on our front living room floor – fair promised myself it’ll be gone by the time you get back here. If you knew the efforts I’ve been putting into this place to get it spic and span for when you return, my love. Even upturned three of the flagstones in the back yard, fair did my back in doing it – because you said you’d always missed a garden. Of course I can’t give you a garden where we are – you know there’s none of us in our street that has one – but now there’s a decent square of earth you can plant something in when you get back. You won’t recognise the house when you do come back ! All to make up for the times I’ve let you down – because it breaks my heart, it does, to remember them, and remember all the moments I’ve made you unhappy, when marrying me should have been the happiest thing ever to happen to us both.

Anyway, I want to get this letter up to the top of Fishergate Hill before five o’clock, so I’ll end it here. I’m counting the hours down to seeing you again, my precious, my one and only, my life.

From your beloved, Arthur

19th September, 1955

Your letter arrived this morning, and I’m writing back straightaway. It’ll be a short letter because I want you to get this tomorrow, or at least by Friday. It was so nice what you wrote, Arthur. You didn’t need to feel so bad. Couples quarrel, and then they make up. You can’t expect a couple to marry and not quarrel ever. It’s what marriage is about. My mother told me the same thing. “Alice,” she said, “it’s about learning to get along with one another,”

We went together to Loch Lomond for our honeymoon. Do you remember that? 1952. Fancy that. Coronation year. You kept saying they should be celebrating our wedding! You were such a joker. And we went to that hotel and there was no-one in it the whole time and you said it was run by a ghost! Such a beautiful place. It made me sad on the train thinking about it. I don’t know why. I remembered it all as I sat there. We went past Hebden Bridge and I thought of your cousin Clifford. And that poor wife of his who’s now dead. Miriam.

Anyhow, this is a short letter because I have some bad news. I’m not coming back next week. I wish it were different, Arthur, but you know the reason why. Maybe you pretended you didn’t know. I don’t know what you’re thinking nowadays. I wish I could come back tomorrow. But at the moment it doesn’t look likely to happen.

In the meantime, to be practical, you can do four things while I’m away. 1) buy a brick of soap from that shop on Osborne St and wash the step down. It looks filthy. 2) Order three bags of coke to put in the back (oh and wash it out with a bucket of water before you do – there’s a nasty smell in that outhouse). 3) Get James to fix that drying rack in the living room so we can dry clothes again without them freezing outside. 4) Buy a small tin of paint from that shop on Fishergate and paint the front door a new coat of red. It’s peeling away.

Hoping to see you soon.

Yours, Alice xxxx

23rd September, 1955

My love,

You won’t believe how sad your letter made me. Even though it was short, a tiny patch of a letter, it fair broke my heart. I got it two days ago and have already done all the things you’ve asked, barring the drying rack. I think James is away in Morecambe until next week. As soon as he gets back I’ll put him straight to it.

You say I know the reason why, but I don’t want to think about it. It pains me so much – if you only knew how much it hurts me – to think of it. It’s like something cutting right through me, stabbing me in the chest and going all the way down inside me. I wish there was some way I could make it up to you. My love, you’re the centre of my world. Everything I’ve ever done, I’ve ever been, revolves around you. I wish there was some way I could make you believe this.

Of course I remember Loch Lomond! I had tears in my eyes when I read those lines you wrote. The ghost hotel! You didn’t mention the little ducks, either, which always walked into the restaurant every morning. Or the Triumph the locals let me have a go on. I’ll never forget those memories as long as I live.

The house is so silent now. When you’re here, you often have the radio on, and you’re listening to some jingle or another. Even when I’m upstairs, reading my paper or practising my breathing exercises and my voices, I hear it going on. Now there is nothing in the house, only silence. I find myself wondering where you are, what you’re doing at this precise moment, as I write these lines. I wish there was a way I could reach out to you. I wish I could find a magic genie to fly me over to you on a flying carpet. But you’ve told your mother not to take my calls, and all I can do is wait until you forgive me. Until you come home and bring life back into this cold, empty house.

But I am making things good for your return, my treasure, you’ll see soon enough. I know how much you like tomatoes so I’ve started planting a line of them in that small square of earth I’ve made in the back yard. Albert Smart from work says there’s no point trying to grow anything in peat, which is what all the back-to-backs here are built on, and I must admit it looks like peat, but let’s see. Maybe I’ll have to dig it all out and replace it with proper soil, although for some reason I really don’t want to do that until I’m sure. You’re right about the outhouse, too. Even though it’s washed out now and filled with coke, it still smells a bit funny.

Speaking of work, I’ve got into a bit of trouble. No, no, before you start worrying, I didn’t start anything – and Mr Kenny’s taken my side, as well. One of the lads at work made a horrible remark about you. You remember, they saw you once last year, that day you dropped by to tell me your Auntie Elsie was coming down from Keighley for the day. Well, of course I didn’t stand for it, especially since the thing he said was so horrible, and downright rude, that if I’d let it pass they’d have made it another one of their jokes. I love you so much, my precious, I can’t stand them saying your name with their evil, filthy mouths. Anyhow, I clipped him one, right on the chin. Mr Kenny called us both into his office and I explained everything as it had happened. He might be a harsh man, Mr Kenny, but he’s got a sense of decency. So I’m alright for now – as long as the others don’t jibe me for it again.

All of this would be meaningless if you were here now. I wouldn’t care about any of it if only you were here again, and not on the other side of the Pennines. The emptiness is driving me mad, giving me desperate thoughts – as if I wasn’t already an oddball, as the lads at work say. I’m going around the house, finding fault with the slightest thing I see, so that I can fix everything ship-shape and Bristol fashion. That stain in the living room is still there, despite all the work I’ve put into cleaning it. I didn’t even notice it at first, because the sofa is over most of it. But when had to push it back last week to get a two-penny piece I’d let roll under, that’s when I saw it. I’ve no idea how it got there – I don’t remember seeing it when we moved in. Maybe because at first we had those cheap carpets we bought from Pinders in Longridge. Do you remember going there? How exciting it all was. We had thirty pounds that your Grandad Levi gave us – to buy any furniture we wanted! It breaks my heart to remember how happy and giggling you were in those days. I can’t even write these lines without bawling like a baby, remembering it all.

Please come back. Come back now. Come back to where you’re loved, where you’re needed. Don’t make me wait any more. I’ve learned my lesson.

Arthur

26th September, 1955

Arthur,

You are a silly person. All these sentimental letters you’re writing and all. Like I never loved you, or I’ve stopped loving you now. What a silly person you are! And saying you’re wondering where I am, as if I’m wandering about somewhere on the moors – you know exactly where I am, you foolish boy!

I hope you are feeding yourself properly. Look – even when I’m not there, I’m worried about you. Like a mother I am sometimes, to you. Really. I hope you’re not just buying fish and chips on your way back from work. You need to be eating something healthy. Vegetables, carrots, something green.

I’m sorry you’re having problems at work, Arthur. You need to keep a tab on that temper of yours. You’ve always had it, Arthur. Don’t let anything they say get to you. Most of that Walmsley’s crowd aren’t even half as educated as you. I’ve never met anyone who’s read so many books. Most evenings you’ve always got your nose in a book. What do those yobs know? More fool you for letting them get to you.

I remember Pinder’s as well. I remember the musty smell of the place. And the big Persian carpet we bid for – didn’t it have an old letter in it, or something? And that old wardrobe that we bought and then gave back cause it didn’t fit upstairs. Good old Grandad Levi. We were flush with money. You sang George Formby songs all that week. I’d never seen you so happy.

I hope you did all the things I asked you. Go to Mrs Pemberton – or to one of the neighbours – and ask if they have a pair of ladders to put up them lace curtains for the back room. I asked you about it before, Arthur. I don’t want people from the bank opposite peering into the back of the house.

I don’t know when I’m coming back, Arthur. It won’t be next week, that’s for sure. None of this can be a surprise to you. I don’t know why you’re acting like it is. Anyway, I’ve told my mother you can call me – she’s not happy about it, but she’ll put you through. You know the number but I’ll write it again: Keighley 553 48

Kisses, Alice

30th September, 1955

Dear Alice,

My love. Every morning I wake up now, I keep the curtains open so I get the first bit of sunshine as it comes through the windows. I stay in bed an extra ten minutes, looking at the space next to me. The space where you used to sleep. My life makes no sense without you, my precious. No sense at all. Did you forget me so quickly ? Is there someone else you’re seeing now? If that’s the case you have to tell me, Alice. I need to move on, even though I can’t bear the thought of living without you.

P’raps I shouldn’t start a letter like that. If you were here you’d say to me “Stop getting so worked up about nowt”. Bless you, Alice. Bless your soul, I really mean that.

But you must know why I’m writing like this. I called your mother today. On the number you gave us. She seemed surprised to hear from me, as though you’d never talked about me at all. She said she hadn’t seen you since you went over in June for Keighley Gala day. I said, “Are you sure? How can that be? All the letters I write are going to your house”. She said – this is the oddest thing – she gets them, but just puts them unopened in a pile above the mantlepiece. She said she’d been waiting to hear from you for ages. Where have you gone? I wish you would be honest with me. Or is it your mother that’s not telling the truth? She’s always been a bit cool to me, you know that. Even on our wedding day, everyone said, even Clifford and Miriam (God rest her soul) said, she looked like she was putting on a happy face. Clifford said she was at a wedding, but it looked like she was at a funeral.

Another funny thing happened to me today. While I was walking back up Christchurch Street to the top, I’d just come off work. None of the neighbours would talk to me. The Denhams were there, on the doorstep, with all their kids. I said “Evening, Walter, any luck with the geegees?” (because you know he likes his horses, Walter). And they all looked at me like I was Adolf Hitler. Not one of them replied to me. Even little Tommy, with his trains outside, who always has a banter with me, looked like he’d been told to avoid me. Downright odd, it was. Two doors up, the same thing happened with Mrs Pemberton, whom I’d only just chatted with day before yesterday. I nodded at her and she gave me the coldest, icy stare. What do you think all that is about? You haven’t been writing to Mrs Pemberton on the sly, have you? Telling her things that aren’t true? Because we both know, Alice, that sometimes you do like to tell a tale or two. I don’t hold it against you, my love, but it would hurt me to think you were spreading gossip and lies about me, especially when I do love you so much, so painfully much.

Yesterday I was on my knees all day in the front room, trying to get that stupid stain off the floor. Looks like it’s soaked right into the wood. I used the soap you told me to buy, from the lad with the queer accent in the shop on Osborne Street. Can’t begin to think what’s caused it. Washed it back and forth, left and right, up and down. But after an hour, it looked just as fresh as when I’d started.

Maybe I’m giving up because in my heart of hearts, I’m starting to doubt, Alice. Starting to doubt whether you’ll ever come back. Even though I miss you and love you so much you wouldn’t believe. I would do anything, anything, to have even half an hour of our time back again. I was thinking about the time we went to Blackpool, and it was so packed we waited half an hour just to get an ice cream cornet. Do you remember? “If you could see what I could see, when I’m cleaning windows!” But I’d give my left arm to wait again half an hour with you in a queue, you laughing and giggling and putting your head on my shoulder, and calling me ‘loopy Arthur’.

Arthur

4th October, 1955

Dear Arthur,

I got your letter today, like I’ve got all your previous letters. I’ve read every single one. How can you doubt that? Why would anyone keep a pile of unopened letters behind a clock on a mantlepiece? My Arthur, you need to keep your wits about you. Don’t let your mind play tricks on you. You know we’ve talked about this before.

You need to be brave now. Braver than you’ve ever been before. You need to look yourself in the mirror. Face up to what you’ve done. It’s really one of those moments, Arthur. Don’t go listening to what other people are telling you, dear. If I’m not getting your letters, then who’s writing this one then? Pull yourself together, get a cup of tea, sort yourself out. I know you’re not a drinking man – that’s why I married you – otherwise I’d be worried you were seeing things after having a tipple. But I’m proud of the fact I’ve never seen you drunk; never even seen you touch a drop.

I do love the idea that you’ve made a garden for us, Arthur, from that back yard. Must have been awful hard work to lift up those flagstones. What are you going to plant there? I’ve always loved orchids, wild orchids. But it’s a bit fanciful for Lancashire, isn’t it? Too cold and wet and grey. I remember my mother getting a bunch of them when I was a child. Not from my father, mind. From someone she’d helped. They smelled so wonderful.

Write to me again, Arthur. Don’t forget me, dear. I’m your wife, remember? The one you married on that April morning. We were both so happy! Just because I can’t come back to you right now, doesn’t mean I don’t want to, Arthur. I look forward to all of your letters. Every morning, as soon as I’m up, my ears are listening for the letter box. Because I’m getting these splitting headaches, Arthur. I don’t know where they’ve come from, but they’re so bad that when they come I can’t do anything else.

I’m stopping here so I can get it in before the weekend post. Keep in mind what I said.

Love, Alice xxx

8th October, 1955

My love,

I have to start with something serious. Not sure what to make of it. A copper turned up at the door yesterday. I’d just got back in from work. I hadn’t hardly taken my jacket off, and there was this right knock on the front door. They call it a copper’s knock, and that’s just what it sounded like. When I opened the door he was standing there, nothing friendly about him at all. He started asking all sorts of questions about you – when you’d gone, why you’d gone. Where I thought you was. I showed him the letters I’d got from you, but it didn’t make him any happier. I even gave him your mother’s number but he didn’t seem to set any store by it. All the time he talked I was wondering what I’d done wrong. I wonder if any of the lads at work had put him on to me. Or even Mr Kenny. I wish I knew what was going on. I wish I knew where you were.

It’s odd you’re getting those headaches you wrote about, because they sound exactly like mine. Splitting ones, from ear to ear. Headaches so bad if I put my hand on my head I can feel them beneath my skull. The pain’s so bad it’s messing with my head. I’m sure some of it is to do with you. I’m not blaming you, my love. But I just can’t carry on like this. It’s not that I’m giving up on you, Alice. I’ll be in love with you for as long as I live. But I’ve a feeling you’ve gone away for good, despite all you say. I don’t think you’re ever coming back. So I’m thinking I should maybe sell the house – it was only ever in my name anyway – and move somewhere cheaper.

You can’t know this, my love, but I’m crying as I write these lines. At the thought of leaving this house, where we’d been so happy together. Where we were going to build a future for ourselves; so many happy things we had planned. I don’t know where it all went wrong. Sometimes my head is so full of people I can barely think, all of them trying to help me, and get things sorted out. But maybe all I need is just a change of scene.

Anyway, that’s that, I suppose. There’s nothing much more to add. If you saw me writing this letter you’d see I was a wreck. There’s a lass from Dutton Forshaws that keeps passing by at work. You always said I was a bit of a ladies man (I have to smile as I write that). Something might come of it, we’ll see. She seems keen on me. You remember that’s how we met, while I was with Sally (I know you don’t like me mentioning her). You’d pass by Courtaulds every day, although Sally didn’t like it. Anyway, that’s all in the past now. But I didn’t want to lie to you, or keep anything from you. I would never hide anything from you.

Arthur

17th October, 1955

This letter won’t be long, Arthur. It’s one I knew I was going to have to write at some point. Like you said yourself, it’s breaking my heart to write it. You can’t believe how happy I was when we got married, you know. That Saturday in April, it was a bright blue morning sky. You say my mum didn’t look so happy but that’s not true. She didn’t take to you at first, I’ll give you that. She said you were an odd one, and she wasn’t wrong. But she was happy for me that morning, because she loved me, and if I was happy then she was. We had to get Paul and his bakery van to bring three of the guests. What a laugh. There was the two of us, laughing and joking. Breaks my heart to see those photos, it does.

You don’t have to be sorry, Arthur. I understand you can’t stay chained to me forever. Of course you have to sell the house. It’s time for a change, somewhere fresh. P’raps with someone fresh, too. It just saddens me that I won’t have you near, anymore. You won’t even be able to visit me when you want. We had something really good, really beautiful going between us, Arthur. Breaks my heart it’s somehow gone wrong. Who knows how that happened? Maybe it was my whims. Maybe it was your funny voices. Who knows.

Just promise me, before you go, not to put the flagstones back in the yard. Plant something nice there; begonias, hydrangeas, erica, I don’t know. Something to cheer me up. Let me see the big, beautiful sky above. Give me a crown of flowers, of orchids, beautiful wild orchids. Something I can wear like a crown over my head. Every time I see them, I’ll think of you.

Records were procured and submitted at Preston, with the cooperation of the Lancashire Constabulary. Signing officer Detective Sergeant Kenneth Ackroyd and Officer Brian Harris, 7th May, 1962.

About Arthur Mandal

Arthur Mandal is a writer based in Eugene, Oregon (but grew up in the UK). He has published over 20 stories in The Barcelona Review, LITRO, december, 3:AM, The Forge Literary Magazine, BULL, The Stand, The Summerset Review, Under the Radar, Bending Genres and others. He also has a chapbook forthcoming with the acclaimed Nightjar Press. www.arthurmandal.com

- Web |

- More Posts(1)