You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

When his son called him to say he was being discharged, Dale was working on a wiring project at Ridgeview Middle School. He stayed late to finish, wouldn’t get any overtime. The next morning, he got up at 5 a.m. and drove all the way from Gaithersburg to North Carolina. It would normally have taken six hours, but he made it in less than five and a half, praying under his breath he wouldn’t get stopped for speeding.

It took him a little while to find the hospital; it was in a suburban neighbourhood of hushed trees and 70s houses with fake wood siding. The ward was a small set of low rise buildings near a more foreboding tall concrete unit with tiny mesh windows pocking the sides.

He gave his son’s patient number, and the bored dark-haired man at the desk checked his ID. Dale sat at the edge of the waiting room’s lumpy sofa. He watched the dark-haired man fill out paperwork, and noticed the metal detector next to the reception desk. Beyond this, windows looked out a small courtyard. He flipped through car magazines, absently, and then began to watch the fish tank. It was large, rectangular, and full of green pebbles, orange and purple twists of fake seaweed, a gold-glitter castle, and a plastic sunken galleon. A bloated white fish with brown spots drifted amid the rubble.

His son materialized behind a male nurse in maroon scrubs who pushed a metal cart through the metal doors. The cart had DJ’s stuff in it—hoodie and a brown paper bag. DJ looked a little dazed, but he hugged his dad hard, harder than Dale could remember being hugged, though maybe it was his own eagerness at seeing his boy.

They had lunch at a Waffle House, DJ’s favourite restaurant. Dale always joked that it was because DJ’s mom was a Southerner. . . in Florida, wherever she was.

They sat in a booth.

“Scattered. . . covered . . . smothered . . . diced . . . ” DJ told the waitress slowly, knitting his brow as he traced the menu.

“You want ‘em all the way?”

“Everything . . . no chilli.”

“No chilli,” he repeated, smiling vaguely when the waitress left. Dale smiled back, his heart choking him.

The fort was less than forty minutes away. DJ was being quiet; Dale thought, he’s gained a little weight. His boy’s round face was softer, like the baby fat was coming back. While they drove over, Dale filled the time by talking about the Redskins’ season, though neither of them followed football much. “You remember when you were five, and we went to Wilmington? You made us pull over in Cape Fear to look for Venus fly-traps.”

“Oh yeah?” DJ asked, his eyes slightly dilated.

“We should go back there,” Dale said, eyes watering. “Next time you get some leave.”

It was only when they were getting near that he started to speak his mind. “You’ll take your medicines? It’s . . . you . . . you think you’re ready—”

“They’ll clear me before they send me back out, pop,” DJ said, placing a limp hand over his dad’s hand, which gripped the transmission. “Desk duty a little while.”

They idled through the visitor line of cars, past the perimeter fences. DJ’s best friend Jason met them at the canteen, where they got Dr. Pepper’s from a vending machine—“I insist, my treat,” Jason said, extending dollar bills to the machine. DJ and his dad didn’t laugh.

“This your first time at Fort Bragg, Mr. Riley?”

“Oh, no,” said his father, trying to smile. “Been here at least a few times.” He was dreading the drive back, but he couldn’t stay, couldn’t get more than a day off on short notice.

DJ smiled vaguely, beatifically.

“We’ll take good care of him,” Jason said at the door, clapping a strong hand on Mr. Riley’s shoulder. Dale hugged his son one last time.

When he had gone, when they’d waved away his Chevy Cavalier and watched it fade back through security, Jason turned back to DJ. His buddy, he could see, was drugged as all fuck.

*

The Seroquel made DJ edgy and fuzzy-brained. Sleep was not sleep but a vacuum into which sound vanished to be replaced by a tremulous suck. It was like donning noise-resistant headphones on the UH-60.

This version of oblivion tossed him back up every morning before dawn. He woke to his leaden heart stamping his chest, and lay in bed watching the bleary light come through the blinds of his stupid little army apartment, the mattress shoved in a corner. He heaved and tossed the sheets around, begging sleep to knock him back down.

Then suddenly, he stopped. He tucked his breath, thought: slow, slow. He became “hyper-vigilant.” He began to inch his index finger, wrist, and palm toward the bedside table, began to move so slow the movement would scarce be visible. But it didn’t matter.

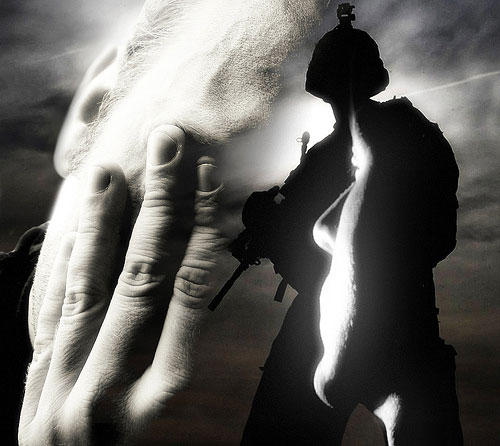

Death was in the room again, reeking of incinerated metal, leaving her yellow sulfurous smear on the windows and floor.

“Go away,” he moaned, and threw a lumpen arm over his eyes.

“Think of the blood.” Her voice was shrill, lunging directly at him in a metallic spiral yet echoing everywhere.

His mind panned over the wreckage smoking the gray craterous rocks the mangled bodies inside. “After we landed, I was the first off and the last one to get back on,” he said, with the flat cadence he used for reporting to a superior. The night after responding to the accident, after they got back to the base, the mess served up spaghetti splattered with red sauce and huge chunks of meat. He took one look at the plate, and puked in his mouth.

“What do you know about Death?” she taunted. He could feel her hovering over the mattress, and her stench stang his nostrils.

“We were the closest.”

“When you go back, don’t sleep,” Death shrieked. She dragged from him thoughts he was trying to hide, facts about the velocity of bullets and fantasies of gasoline burning his throat.

*

Dale watched boys in camouflage, dark berets, and sand-coloured boots carry them down onto the tarmac. It was a cool October night. A little standing area with a carpet had been set aside for family members. He stood beside an ashen faced couple, older than him. A beautiful black girl in a red sweater stood a little bit apart, tears tumbling down her face. He watched the six gun-metal-gray caskets and thought numbly, wonderingly, which is DJ?

He hadn’t allowed himself to think it. His boy had problems, but he had been promoted to crew chief the year before, and they’d told him he would be back to flying helicopters soon.

He didn’t allow himself to think it until he called Maragit — DJ’s ex, his grandson’s mother, a quartermaster who was stationed at Fort Campbell in Kentucky. “Oh God,” she moaned. “He did it. He finally did it.”

Dale was waiting to hear back from Arlington about the date when he got the CID report, with “non-combat related injury” printed near the top.

DJ had been found alone in an SUV parked within the security fences in Kandahar Airfield. The records said they had taken his gun away a few days after he arrived there. He was found with a single bullet hole in his head, and his roommate’s M-4 at his feet.

DJ had placed his phone on the windshield. It lay open to an unsent text message

im so sorry pls u + god forgive me

*

Before they had finished laying the earth, Dale and Maragit walked out of the section. They didn’t speak. It was a gray day, with a touch of wetness in the air. Dale wore an olive raincoat, and his shoulders were more hunched than usual. He thought of the first time he’d met Maragit . . . at Christmas three years ago, when she was already pregnant. She and DJ had come on Christmas Eve, and driven late that night to her family in Indiana. Dale had thought DJ would be embarrassed by his little bachelor condo, with its Walmart furniture and meals cooked in one pan, so he’d taken them out to the steakhouse near the interstate and there — his Christmas present, DJ told him the gyno said it would be a boy and that they were going to name him Dale the Third, in honour of his grandfather. “Keep a good thing going,” Dale Jr said with a wink. Dale had been so overcome that he couldn’t say anything for a minute . . . when speech returned to him, he tried to make a joke about what nickname could you call him, DT, D the 3. Maragit said, oh no, not like some video game. But that’s what he and DJ called him.

Dale wanted to ask her about D3, whose middle name was Aaron. Thinking of it now, unable to look at Maragit’s severe face, he wondered if Aaron would become his grandson’s name.

The trees were breaking with fragile autumn colours. He and Maragit climbed a hill, past bare magnolia trees. They walked deeper into the rows of neat, identical white. When they turned around the view surprised them. The stark points of Washington’s spires and monuments followed the curve of the Potomac, soft on the horizon.

About Ingrid Norton

Ingrid Norton's essays, fiction, and reportage have appeared in publications such as Boston Review, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The St. Ann's Review. She is a doctoral student at Princeton University, and a former editor and journalist. Norton is working on a novel.