You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

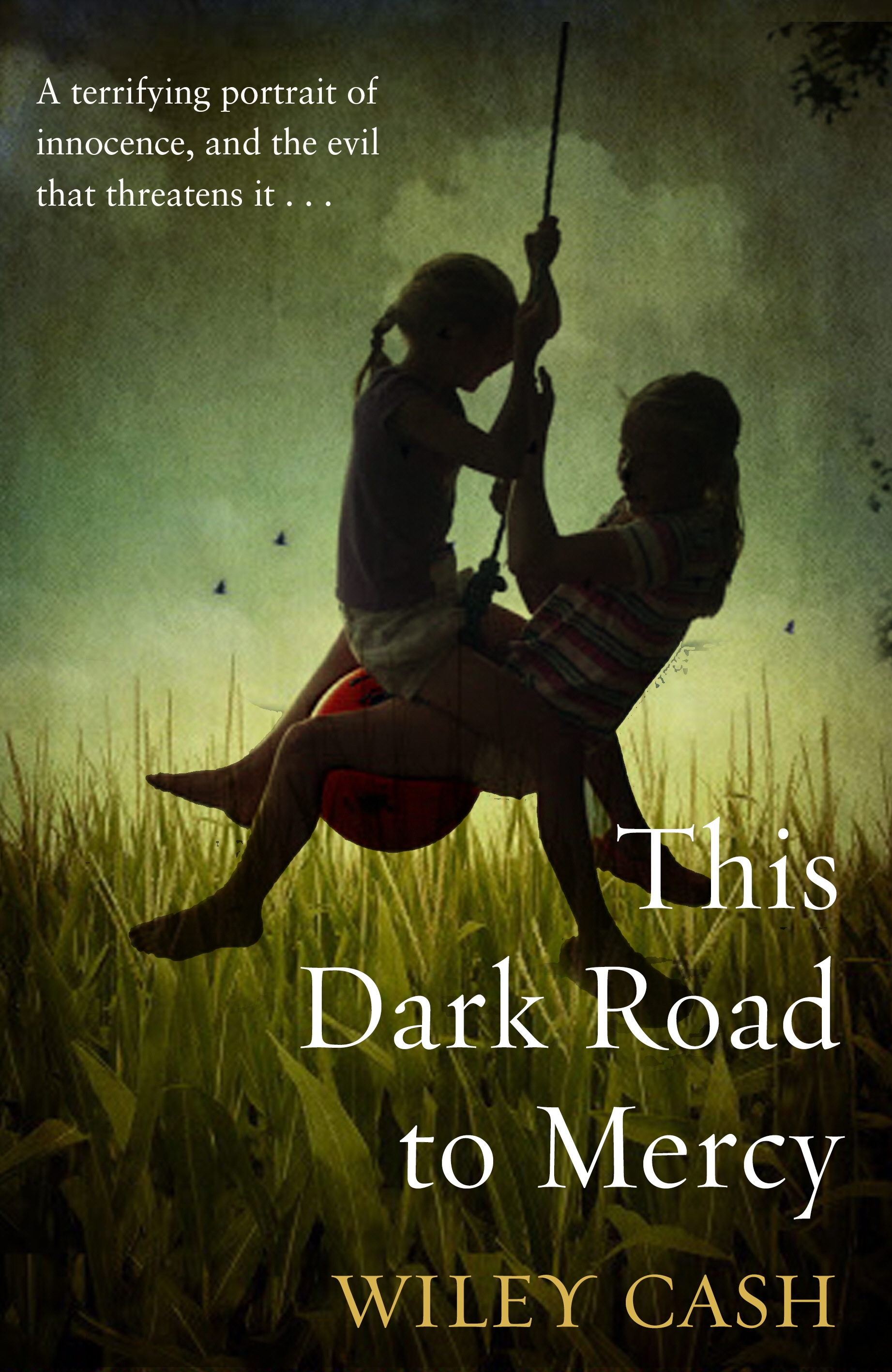

The inspiration for This Dark Road to Mercy began with a beautiful story my wife told me about her childhood, and this led me to recall a tragic story from my own past. I’ll begin by sharing the story I heard, and then I’ll tell you about the story I already knew.

According to my wife, when she was a little girl she was an incredibly talented baseball player, but she had only one weakness in her game: she didn’t know how to slide into base. To remedy this, after her father arrived home from work in the summertime, the two of them would walk to the baseball field behind the grade school she attended, and they’d take turns sliding into third base, her father lending his encouragement and offering tips to help her feel more comfortable.

I invite you to picture the image she painted for me: it’s dusk on a summer evening in the American South; a father and his daughter are alone on an empty baseball field, taking turns sliding into base; the sound of crickets rises from the woods on the edge of the field; fireflies glow in the dusk; a car quietly passes on the road in front of the baseball field and slows down for a moment, taking in the scene. The car’s windows are down and you are inside it: you can hear the crickets, you can feel the warm, humid air, and when you look out toward the baseball field, what do you see?

My wife’s story is an emotionally touching story to hear, and I wanted to write about that girl and her father, but I knew it wouldn’t necessarily make for a compelling read. Readers like more complications, more drama, less innocence and purity and much less simplicity. So I reimagined the scene: the little girl is out there playing ball with her friends one day after school, and when she slides into third base she stands up, dusts herself off, and spies her father sitting up in the stands, watching her. All she can think is Why is that loser here?

When it came time to write my second novel after the publication of A Land More Kind Than Home, I returned to the story my wife had told me, and I once again conjured the image of the lone girl and her loser father, and I thought of ways to complicate it. I wondered if this girl had a younger sibling she had to care for, and it was then that I remembered two young girls I’d known growing up in North Carolina. They were foster children, and when I met them they were being raised by an elderly couple that went to my church. The oldest girl was my age, and her sister was about three years younger. I knew them for a few years, but eventually they went back to live with their birth mother, and I never saw them again because we didn’t go to the same school.

A few years later, I heard the girls’ names on the local news; they’d been murdered by their boyfriends, two grown men who suspected the sisters of stealing drugs from them. The oldest was fifteen, and her sister was twelve. The two men had picked the girls up at their mother’s home the night before and driven them out into the country. There, at the base of a mountain, they cut the girls’ throats, buried them in shallow graves, and covered their bodies with lime.

I invite you to picture the image that has been in my mind for years: it’s well past dark on a weeknight in the American South; two young sisters are riding in a truck with their much older boyfriends, both of whom seem nervous and don’t have much to say; the streets are empty, and the girls hear the sound of the truck’s tires as they move from pavement to gravel and then to dirt; the driver parks the truck and tells the two sisters to get out; once they are outside they hear a car pass quietly on the road not far from where they’re standing, but they know no one can see them through the thick trees.

After almost twenty years, I found that I couldn’t stop thinking about those two little girls and the tragedy that had befallen them. I wandered about their lives, about a mother who would allow her minor daughters to date grown men, about grown men who would murder children in cold blood.

Before I knew it, the story of the two sisters merged with the story my wife had told me, and I began to add my own fictive elements: two sisters are languishing in foster care; their missing father returns and kidnaps them, desperately hoping for another chance at raising his family. But things can’t be that simple. Hot on the father’s trail are two very different men: a violent bounty hunter with a years’ old vendetta and an ex-cop who’s the girls’ court-appointed guardian.

This Dark Road to Mercy was inspired by both beauty and tragedy, innocence and evil, and these conflicting elements drive the novel. The two girls in my novel don’t suffer the same fate as the two sisters I once knew, but they nonetheless are forced into an adult world before they’re emotionally prepared to confront it, and their lives will never be the same. But, at its core, the book is about mercy, and that’s what the two sisters in my novel are shown. I only wish that the two young girls I knew could’ve been shown the same mercy. Their tragedy haunts me still.

We pick the most exciting new titles out there for the Litro Book Club, and you’ll get them sent to you before they hit the shops. You’ll get access to live author Q&As, and the chance to see your reviews published on the site. It’s a great way of meeting like-minded book-lovers too. Join the Club

About Wiley Cash

Wiley Cash is The New York Times best-selling author of A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME and THIS DARK ROAD TO MERCY, which are both available from William Morrow/HarperCollinsPublishers. His stories have appeared in Crab Orchard Review, Roanoke Review and The Carolina Quarterly, and his essays on Southern literature have appeared in American Literary Realism, The South Carolina Review, and other publications. Wiley teaches in the Low-Residency MFA Program in Fiction and Nonfiction Writing at Southern New Hampshire University. A native of North Carolina, he and his wife currently split their time between Morgantown, West Virginia and Wilmington, North Carolina.