You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

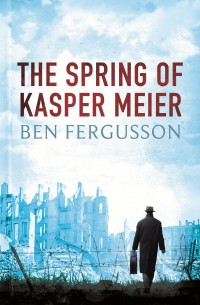

Go shoppingWe recently interviewed Ben Fergusson – author of our current Book Club read, The Spring of Kasper Meier – and asked him about the importance of travelling and living abroad for a writer. Here he goes into greater depth on the issue of living in Berlin, and how it changed the way he thought and wrote.

Inspiration

Living abroad is of course highly inspirational. For me, in Berlin, this was partly to do with the history – the bullet-strewn walls, the gaps in blocks of housing, the crumbling sections of The Wall – which I’ve talked about in more detail in an earlier post. But it was also to do with more quotidian things, like the weather. I remember experiencing my first proper snow fall and it feeling so different from home – large soft lumps that settled into great drifts and freezing cold air that seemed so ‘Eastern’. These differences literally transport you somewhere else – you spend a few thrilling seconds imagining that you are walking through post-War Berlin or 1970s East Berlin in a cold winter and stories begin to form themselves automatically.

Once I was writing the book, it became very easy to wander or cycle somewhere and imagine that I was Kasper or Eva or any of the characters in the book and start to notice things as they might have noticed things. It became a perfect set to project my imagination on, especially when the layers of the city’s past history were so evident.

Distance

It has always been the case for me that having a little distance on my subject helps me to clarify what I want to write about. In honour of the cliché that you should ‘write what you know’ I have often planned, begun and completed unpublished pieces that are much more related to the realities of my life. I never felt these worked as well. The issue is the ability to judge what is unique, important or interesting about a story. I find that trying to interpret my own life feels rather like standing too close to a modern painting, with far too much detail to pick out the patterns and connections that create the broader narrative. In Experience Martin Amis said that he has to be 10 years away from any phase in his life to write about it, and this makes sense to me. Perhaps my great satirical novel of life as a publisher of art books will have to wait until I retire.

There is also a wonderful distance you get from speaking another language and being out of your regional context. If you learn the language, you are stripped of those elements of region and – importantly for Britons – class, that people immediately hear when they speak to you in your own country. All that people in Berlin could hear in my accent was that I wasn’t German; if I told them that I grew up in rural Oxfordshire it didn’t mean anything to them; if they found out that I went to state school, it was meaningless in a country where everyone goes to state school. Being stripped of context is hugely liberating as a human being in general, but particularly as a writer when your job involves inhabiting lives that aren’t your own.

Difference

A few things happen when you spend an extended time abroad reflecting on cultural and social difference that feed in to how you write, how you think about your characters and the things that make them unique:

You first see all the elements in another culture that are very different from your own. In Germany, this was in part the way people talked and interacted. There is, for instance, a formal ‘you’ in German and this changes the way you talk to people and formalises when you are friends. There is the famous German honesty, which can feel cutting it you’re English, but also can be hugely warm – if someone says ‘we should meet up for a beer sometime’ they literally mean ‘let’s go for a beer next week’ not the English ‘nice meeting you, but we’ll probably never speak again’. It was also the food and the relationship with food. This wasn’t just what people ate – like hundreds of different types of bread and a whole supermarket counter for sausages – but also how people ate: breakfast is a bigger, slower meal, dinner can just be a slice of bread and some cheese, lunch should be hot. Taking this into consideration in your writing isn’t just about veracity, it’s also about using these cues to help form the characters and relationships that you’re writing about.

When you notice all this, you begin to see all the things that are unique to your own culture. This counts whether you’re writing about the place you’re living in or not. There is of course food and language, but also how you place yourself in the world. I came to realise what an island nation we are in the UK and how little we worry about our borders. In fact in Germany Britain is often just called Die Insel (The Island). They also find it completely strange that we talk about ‘Europe’ and ‘The Continent’ when we’re in Europe and part of the continent. In my case, this is formative for my characters – what is it like to grow up in a country that forms itself afresh every twenty years? But also, when I now write about British characters, I’m also often thinking, ‘Is this something they’re thinking because this is innate to this character or is this because they’re British?’ The moment you feel that a character is holding on to their nationality to gloss over something more complex, the character – and the narrative – becomes far more psychologically interesting.

When you inhabit that new culture you also begin to see the lack of difference. This is vital in writing a novel set in another country and is something that begins to form after you’ve been away for an extended period. It is the basic sense you get that, on an emotional level, there really is no difference between you and the people around you; that the subtle differences are fascinating, but at the end of the day don’t really mean anything significant in terms of the characters’ humanity. This is a key realisation if you want to properly inhabit a character. If you’re still thinking ‘what would a German do?’, then you’ve not lost yourself enough.

All of these elements, even if they weren’t things that were directly used in my writing, jarred me in the best possible way and allowed to write a novel that I would never have attempted had I never left ‘The Island’.

We pick the most exciting new titles out there for the Litro Book Club, and you’ll get them sent to you before they hit the shops. You’ll get access to live author Q&As, and the chance to see your reviews published on the site. It’s a great way of meeting like-minded book-lovers too.

Join the Club

Read the book?

Tell us what you think on the Book Club discussion page.

About Ben Fergusson

Ben Fergusson is a writer, editor and translator and has worked for ten years as an editor and publisher in the art world. His short fiction has appeared in publications in both the UK and the US and has won and been shortlisted for a range of prizes. From 2009-2010 he edited the literary journal Chroma and since 2013 has been the editor of the short story magazine Oval Short Fiction. His debut novel The Spring of Kasper Meier is the Litro Book Club summer read.