You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

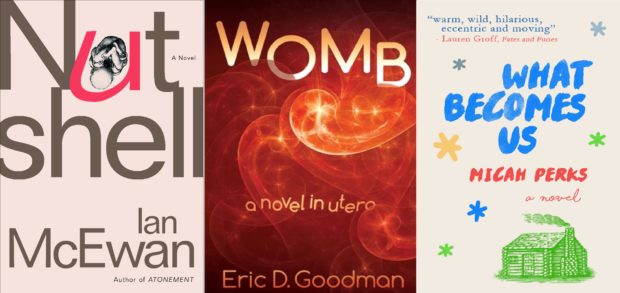

We’ve encountered unusual narrative perspectives before. Psychopaths, death, the colour red – they’ve all been attempted. But foetuses feel new. Or felt new, momentarily: in the space of a year, three foetus-narrated novels have arrived at once. The first, Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, sidesteps the obvious restrictions on the pre-natal narrative voice by making his foetus a well-educated one, absorbing the ideas of the podcasts to which his mother listens. Nutshell borrows its framework from Hamlet; our unnamed narrator listens in as his mother and uncle (Trudy and Claude, a not-so-subtle take on Gertrude and Claudius) conspire to kill his father. This reworking of Hamlet in utero has remarkable moments. I enjoyed the pleasure the foetus takes in sound and motion, and his sensitivity to the workings of his mother’s insides (her anxiety is measured through the hurry of her heartbeat and the churning of her bowels). And the relocation of Hamlet’s predicament to the womb is curiously convincing. McEwan heightens the claustrophobia in Hamlet, tightening its themes and narrowing its focus. Where Shakespeare’s protagonist is unable to make a decision, this unborn Hamlet is robbed of any agency at all. His worst fears are realised with lively derision: ‘Not everyone know what it is to have your father’s rival’s penis inches from your nose,’ he comments.

Occasionally, the Hamlet references come too frequently. ‘It’s what we should have used,’ Claude says. ‘Diphenhydramine. Kind of antihistamine. People are saying the Russians used it on that spy they locked in a sports bag. Poured it into his ear,’ just as the ‘juice of cursed hebenon’ was poured ‘in the porches’ of King Hamlet’s ear. Later, desperate, the foetus intends to kill himself with his umbilical cord, ‘three turns around my neck of the mortal coil.’ Arriving into the world, the newborn remarks that ‘[t]he rest is chaos.’ And the title itself is lifted from Shakespeare. ‘Oh God,’ Hamlet says. ‘I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.’

This feeling of boundedness is the book’s most interesting quality, and McEwan is largely successful at limiting the narrative to the experience of the foetus. The novel is at its least effective when we hear McEwan creeping into the womb to voice opinions of his own. At one point, the foetus angrily informs us that the ‘almost-educated young’ are ‘on the march… longing for authority’s blessing, its validation of their chosen identities.’ He envisages ‘the special campus safe room equipped with Play-Doh and looped footage of gambolling puppies’, a protection against ‘inconvenient opinions’. This stab at identity politics has no obvious place here; the tentative link is that the foetus’ mother ‘marches with a movement’ in ‘identif[ying] as innocent’ when she is guilty. It is a jarring passage, for – of all narrators – a foetus feels a likely advocate of safe spaces.

These authorial interruptions are the book’s greatest shortcoming, and it is for similar reasons that the second of our foetus-centric novels also exposes itself to criticism. Womb: A Novel in Utero by Eric D. Goodman is to be published early next year by Merge Publishing. Like McEwan, Goodman rises to the challenge posed by the foetus’ limited perspective, relating a story of betrayal and domestic turmoil through the filter of the uterine wall. The narrator of Womb is in possession of knowledge beyond his experience, this time not the work of podcasts but of a ‘connection to the greater consciousness’ which ‘allows me to peruse the works of great philosophers and thinkers, to study sociological and psychological experiments, to witness the past and see such theories put into practice in the field’. With such a wealth of insight under his belt, it seems odd that he can’t work out why ‘Mom’ is telling her co-worker Stan about her pregnancy before her husband. ‘I was as shocked as Stan’, we hear.

This disconnect isn’t the novel’s worst offence, however. ‘One of the commonest signs of a lazy or inexperienced writer of fiction is inconsistency in handling point of view,’ David Lodge informs us, and it is this inconsistency – unexpected in McEwan, and abundant in Goodman – that undoes the carefully-constructed conceit around which both novels hinge. Goodman repeatedly places into the mouth of his foetus-narrator the kind of moralising language which doesn’t fit with the playful inquisitiveness of the character. Rather, the foetus’ comment on his mother’s adultery – ‘your wrongdoing will be made right when Brother and I are born’ – reads like the insistence of a puritanical author. What’s more, Goodman’s treatment of Mom, the home of his narrator, is often less than attractive. Through the judgements of her unborn child, Mom is depicted to be unfaithful and impractical, unable to function without the calming presence of ‘Dad’. ‘Everything smelled good when Dad was around,’ we read. ‘[M]aybe I just subconsciously recognized Dad as an ally’. Of the possibility of abortion, the foetus pleads: ‘Give Dad a chance… Let him make that decision.’ By pitting Dad as the embodiment of reason against Mom, the voice of unchecked emotion, Goodman creates a dichotomy which feels unpleasantly two-dimensional.

The narrators of Micah Perks’s What Becomes Us, a pair of unborn twins, are unable to make such impersonal pronouncements about their parents because – unlike the protagonists of the previous two novels – their consciousness is shared with that of their mother. This novel barely touches on the physical reality of residing in a womb, a description which McEwan manages so lyrically. Rather, it focuses on a woman’s relocation from one side of America to the other to escape an abusive relationship and begin a fresh life with her soon-to-be-born children. The foetuses report on their mother’s new home in a small community on the east coast and her interaction with the local history. She becomes obsessed by a book by Mary Rowlandson, a colonial woman captured by Native Americans in the seventeenth century, and believes herself haunted by her ghost. The hunger Rowlandson felt in captivity preoccupies her, and the book lingers on descriptions of food.

There is much to praise here, specifically an absorbing cast of characters who address the problems of their past in idiosyncratic ways (one woman, for example, ‘can’t stand the fact her daughter snorts coke and doesn’t go to Church and fornicates outside of wedlock and never calls here, so she killed her off in the twin towers’). The novel offers moments of beautiful writing as it considers, in Perks’s words, ‘this business of becoming I’. But the decision to describe ‘this business’ from the perspective of a barely-there ‘I’ is puzzling. Perks is preoccupied with history and the inescapability of our past; why, then, is her novel narrated by a pair of foetuses without any pasts at all? Moreover, the present tense gives the prose an immediacy which comes to feel quite wearing. The book feels stretched in too many directions at once, attempting to contemplate the past as well as existing only in the present, a character-driven story in which our narrators never actually meet any of the other characters. This conflict between form and intent explains why Perks so rarely delves into the experience of the foetuses, why she insists that they share the thoughts of their mother.

There is a common thread to these novels. Perks examines the mother’s journey from past to present: determined to erase her own history, she embarks on a reinvention of self to match the invention of self happening inside her. Goodman laments the loss of unlimited knowledge. After the baby’s birth, his language fragments into staccato-sentences: ‘Mommy. Daddy. Holding. Hugging. Heartbeats. Gush Glow. Grin. Laugh. Floating’. And McEwan’s newborn mourns the ‘private ease of Mother’s womb’, as Thomas Gunn wrote so memorably in ‘Baby’s Song’. Gunn’s baby wishes to be ‘put… back/ Where it is warm and wet and black’. Now, ‘raging, small, and red’, he knows that while things may be forgotten, ‘I won’t forget that I regret’. This regret, a startling sentiment in narrators who haven’t yet lived, permeates all three novels.

Nutshell was published by Jonathan Cape in September and is available in hardback for £7.99; What Becomes Us was published by Outpost19 in October and is available in paperback for £12.91; Womb is published in spring 2017 by Merge Publishing.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.