You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

What makes us laugh? Misfortune – epitomised in the act of slipping on a banana skin – is endlessly funny. The luckless characters of Chaucer’s fabliaux bring us famous examples of this, and, a little later, Malvolio’s yellow-stockinged incarceration does the same. Indeed, Malvolio’s plight marks one of the earliest recorded uses of the term “stitches”. Maria commands the others: “If you desire the spleen, and will laugh yourself into stitches, follow me.” “Stitches” then, as now, attests to a sharpness, a pain, felt by the laugh-er, but also, we presume, by the laughed at, and this pain is acknowledged in the ius nocendi or “right of injury” that Horace believed comedy to possess. Laughter is too often cruel (we’re never really “laughing with”, are we?). And British laughter: might that be the cruellest of all laughters?

Twentieth-century literary laughter has a lot to do with class, and the butt of such jokes are rarely treated benignly. The Bertie Woosters of Wodehouse’s imagination, and the Reginalds between Saki’s pages are endlessly mocked; cruelly so, perhaps. In Saki this has a sinister edge. His short story “The Reticence of Lady Anne” describes Egbert’s “quarrel over the luncheon-table” with his wife Lady Anne, and her subsequent “defensive barrier of silence”. He protests and cajoles, to no avail; only later do we hear from Don Tarquinio (the cat) that Lady Anne “had been dead for two hours”. Similarly, Evelyn Waugh brings his comedy to levels of near-hysteria before his characters burn out spectacularly and unhappily.

But when we read these books – or, to look elsewhere, the endearingly strange works of Douglas Adams, the wince-inducing musings of Adrian Mole – are we really laughing? No, said Ned Beauman in a conversation with scriptwriter-turned-novelist Jesse Armstrong. We’re not really laughing. Beauman, who has himself been hailed a success in comic-writing spheres, observed that he would feel fortunate if his writing elicited a “weak smile” from his reader. That is the remit of comic novelists these days: the uncertain lips of idle commuters. Forget roars of laughter, or wiped-away tears. The power of novels lies in weak smiles alone.

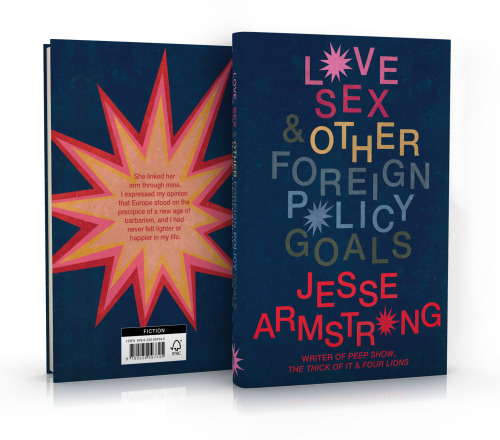

Perhaps this is true. Yet Jesse Armstrong does much to remedy this in Love, Sex & Other Foreign Policy Goals, his debut novel about a group of idealistic youngsters in the 1990s who plan to take a travelling play to the war-torn Balkans, bringing with them a host of risible inadequacies and sexual tensions. You will know Armstrong from his work on Peep Show and The Thick of It, and his ability to read people, to capture exactly their uglinesses and their faults, translates well into a novel. His characters are completely believable: from the incessant question mark which punctuates every one of their sentences, to their focus on the menial even as they drive through devastated villages (“a nudge of Christian’s Adidas shoulder bag a few centimetres into my footwell felt like a thumb pressed on my windpipe”, our narrator complains).

Beauman suggested that the selfishness of Armstrong’s characters points to a pessimistic world view (a “Dostoevskyan nightmare-scape”). With such self-interested pettiness dictating human behaviour why, he asked, his expression serious, “don’t we just die?” Armstrong replied with, perhaps, the most interesting revelation of the evening: that despite writing such unlikeable characters, despite hating the company he keeps “over half the time”, he still considers himself an optimist. He subscribes to Updike’s interrogative outlook (“my work says, ‘Yes, but.'”, Updike explained in a Paris Review interview), asking and asking of his characters until they are entirely exposed. Not a misanthrope, then. Seeing the best in people even as he leads them into minefields to relieve themselves (one of the funniest episodes in the book, actually).

Beauman tried a different tack. If you don’t hate them, do you admire them? Do you envy the passion with which these students take their sincerely-crafted, if terrible, play into the Balkans? Armstrong laughed again, and admitted to being a liberal. His position is to be open to lots of positions. So, no. He doesn’t envy the students their single-mindedness.

The book is funny; a “money-back guaranteed” kind of funny, Beauman said (and that’s Beauman’s money, Armstrong was quick to add). It’s cruelly funny – Armstrong even slips a banana skin beneath his protagonist’s feet at one point – and self-referentially so:

As we made our way towards Slovenia, Christian’s delight increased steadily. He started to laugh as he read. That is always irritating. “What’s so fucking funny, friend?” you want to ask of this person off on their own, having a good time with an author right in front of your face while you’re trying to mind your own business among all the horror in the world. He banged a fist into the seat in front of him. “Oh man, this is it!” he said and crossed his legs with merry abandon.

But it also raises plenty of questions about the funniness of idealism, of earnest art. And it deals bravely with issues of the Bosnian War and Britain’s position of non-intervention. As we have seen elsewhere – in Four Lions – and as we significantly haven’t seen elsewhere – in his unproduced screenplay Murdoch – Armstrong isn’t afraid to address “difficult” subjects.

In light of this talk I left the book with a feeling of admiration for Armstrong’s self-professed optimism. If you can live with this really unloveable bunch, their rising lilt ringing in your ears day after day (after day?), immersing yourself in what Beauman called a “Hobbesian universe” in which people make only “ephemeral associations”, and still maintain a love for your fellow humans – well, I’m very impressed.

Love, Sex and Other Foreign Policy Goals is published by Random House.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.