You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

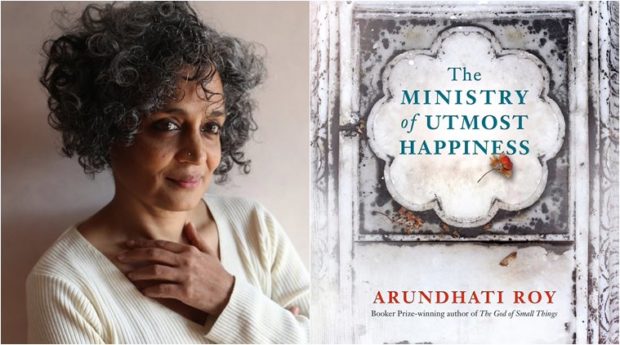

Go shopping A second novel is a tricky thing. If your first novel was a barnstorming global sensation that won the Booker Prize, doubly so. If you then take twenty years to produce that elusive follow-up, well. With the weight of all that expectation, you could sink. Arundhati Roy’s second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, does not sink. It is in many places gripping, moving, and fueled by a burning rage at India’s human rights record. If it doesn’t entirely float, either, that is due not so much to the inclusion of political material per se as to the sheer quantity that Roy is willing to include, a proliferation of detail that doesn’t always pull its weight within the framework of the story.

A second novel is a tricky thing. If your first novel was a barnstorming global sensation that won the Booker Prize, doubly so. If you then take twenty years to produce that elusive follow-up, well. With the weight of all that expectation, you could sink. Arundhati Roy’s second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, does not sink. It is in many places gripping, moving, and fueled by a burning rage at India’s human rights record. If it doesn’t entirely float, either, that is due not so much to the inclusion of political material per se as to the sheer quantity that Roy is willing to include, a proliferation of detail that doesn’t always pull its weight within the framework of the story.

Roy opens with the birth of a Hijra: born as Aftab, our protagonist is quickly found to have two sets of genitals—one male, one female. Though Aftab’s parents attempt to raise their child as a boy, by the time Aftab is old enough to be aware of difference, he knows that he’s a she. A chance sighting of a famous Hijra who goes by the name of Bombay Silk sparks a series of reactions that finish with Aftab’s name change (to Anjum), a move out of her parents’ house and into the house known as the Khwabgah, or House of Dreams, where other Hijras live and work, mostly as specialist courtesans. For a while all is well: Anjum has a career, a chosen family, and adopts a small child whom she finds in the street one day, naming her Zainab. A visit to a shrine in Gujarat, however, coincides with the massacres being perpetrated upon Muslims in the area at the time, and results in trauma that Anjum, upon her return to Delhi, refuses to discuss. Her internalised distress forces her to move out of the Khwabgah and into a nearby graveyard, which she slowly sets about turning into a complex of rooms to which she refers as the Jannat (“Paradise”) Guest House.

Anjum’s story intertwines with the story of Tilottama, or Tilo, a trained architect who becomes a political activist, and the three men who love her: Musa, who takes advantage of the rumours of his death to become a major figure in the Kashmiri insurgency; Naga, a respectable official whom Tilo marries in order to ensure her own safety; and Bilqab, the least assuming of the three, who works in the Intelligence Bureau and engineers Tilo’s release when she is captured by the sadistic captain Amrik Singh. In this strand, too, an unclaimed child generates redemption: Tilo adopts a dark-skinned baby found on the street during a mass protest. The child is named Miss Jebeen the Second in honour of Musa’s daughter, shot by police while on the fringes of a Kashmiri martyr’s funeral.

There is a sense in which Roy’s inclusion of many characters and forms of oppression is generous, giving the reader many points of view from which to access the story. “How to tell a single story?” Roy muses near the end of the book, in a paragraph reproduced in its entirety on the back of the proof copy. “By slowly becoming everybody. No. By slowly becoming everything.” It is an admirable idea in theory, but there are pitfalls to that approach from which The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is not exempt. It is extremely difficult, for example, to differentiate characters. Writing the previous paragraph, I had to pause and think, long and hard, about which lover was Musa, which was Naga, and what Bilqab had to do with it all. There are many minor characters so similar to each other that they might as well be the same person: Saeeda and Nimmo Gorakhpuri, for example, both of whom are flamboyant and confident young Hijras known to Anjum. Both appear, and are named, throughout the book, but there is no sense of each woman as a separate, rounded entity. There is a young man called Saddam Hussein who lives in Anjum’s graveyard and ends up marrying her daughter, but by the end of the book it’s a challenge to recall why he’s there, what narrative function he is fulfilling.

In a way, this might be precisely against the point. Questions of literary efficiency—of narrative function, of plot rationalisation, of what a given adjective or character or event is actually doing in the novel—are mostly absent. That kind of novel, one where every word is weighed carefully, every action accountable for, doesn’t seem to be the kind of novel that Roy is writing. She has said in interviews that she wants to “wake the neighbours”, and if your ultimate goal in writing a novel is to raise awareness, then indeed it can seem entirely right to leave in as much as possible. By following this strategy, Roy achieves inclusivity, but she also gives the novel the appearance of ticking a lot of boxes. Homelessness amongst Delhi’s transgender population? Tick. Drug addiction? Tick. Blameless (indeed, mentally disabled) martyr? Tick. Rape and torture? Tick.

I’m not leveling charges of gratuitousness at The Ministry of Utmost Happiness; quite the opposite. Roy treats these topics seriously and renders to her characters a level of dignity generally not afforded them by Western writers of atrocity porn. To write a good political novel, though—and it is more than possible to do that—you need an emotional core. Roy gives us plenty of personae and detail, but in opening up the focus of her story, she diffuses it. Perversely, an authorial choice that was clearly motivated by a desire to provoke empathy obstructs the fiction reader’s ability to empathise.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is published by Hamish Hamilton. RRP £14.99.

About Eleanor Franzen

Eleanor Franzén is a London-based writer and editorial assistant. She blogs about books at Elle Thinks (https://www.ellethinks.wordpress.com).

This was such a good thing for me.