You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

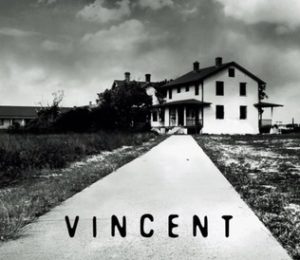

Go shopping “Authorities say a man was stabbed to death, decapitated and partly cannibalized in what appears to be a random act of violence on board a bus that was en route to Winnipeg late Wednesday.” Thus begins Vincent, the third – and most recent – book of poetry by the American author, Joseph Fasano. Unlike Fasano’s first two collections, however, Vincent is a single, book-length poem: loosely inspired by Vincent Weiguang Li’s baffling 2008 murder of Tim McLean on board a Canadian Greyhound bus. For 80 marvelous pages, Fasano imagines the world through Vincent’s eyes: his childhood, his relationships, his dreams and fixations – and of course the murder that’s kept him locked away ever since.

“Authorities say a man was stabbed to death, decapitated and partly cannibalized in what appears to be a random act of violence on board a bus that was en route to Winnipeg late Wednesday.” Thus begins Vincent, the third – and most recent – book of poetry by the American author, Joseph Fasano. Unlike Fasano’s first two collections, however, Vincent is a single, book-length poem: loosely inspired by Vincent Weiguang Li’s baffling 2008 murder of Tim McLean on board a Canadian Greyhound bus. For 80 marvelous pages, Fasano imagines the world through Vincent’s eyes: his childhood, his relationships, his dreams and fixations – and of course the murder that’s kept him locked away ever since.

Fasano writes effusively, and Vincent reads like a psychological bonfire that loses none of its smolder from the first page to the last. A fellow reviewer, Timothy Liu, argues that Fasano’s poem “demands to be read in one sitting. Indeed, the thing held me spellbound with its quiet mania.” Perhaps I lack Liu’s endurance, for it felt strenuous to read more than ten pages in a sitting. Not in a negative way; rather, the way a rich meal makes even the thought of one more bite impossible. Indeed, there are fresh horrors on each page, relentlessly stitched together as a ladder into the inner room of Vincent’s madness: “I went out into the field that night / with my mattress with a crate / of my sisters dolls / she had carved down in the greatest hours / of her sickness / carved off the little nubs / of their breasts like ticks / on the feral or the dull.” And for all of the Stoic restraint with which Vincent portrays his surroundings, the poem itself remains ecstatic, barbaric.

Much of Vincent is filled with memories of a lonesome, disturbed upbringing in rural Canada. Such is Vincent’s imagination and psychological complexity that it’s near impossible to differentiate between genuine memory and recollection from vision and fantasy. There are incidents of animal mutilation, child molestation, abuse, starvation, decay. The entire narrative seems to take place at dusk, late in November, somewhere in the barren fields of the North. Fasano’s world of thin horses and leafless trees is beautifully rendered; his depiction of blank, rural winter is one of Vincent’s true triumphs: “And even the wind was heavier now / like the dresses in the closet / of a drowned girl.”

An unmissable theme throughout is mathematics, strangely enough. On first reading, it’s easy to dismiss, or misunderstand the poem’s constant allusions to complex math, given how the rest of Vincent seems to live on the fringes of a backcountry haze. Vincent’s fasciation with mathematics is certainly an eccentric addition by Fasano – perhaps even an implausible one. But more than anything, it draws attention to the theoretical idea holding the entire poem together: Vincent is not merely an agent of chaos – a monster deaf to everything but the whims of the voices inside his head. Nor is he an oaf. Rather, Vincent’s character is grounded in a complicated, but consistent, worldview – with his own notions of right and wrong, clean and unclean, duty, etc. Depravity, sure; but his is still an inner life rich with memory, loss, desire, and righteousness – just as complex as the mind of anyone on that fateful bus ride.

In this way, Fasano’s poem stares unflinchingly into the misleading stigma that mental illness is somehow the same thing as mental disorder. Disorder, after all, implies a lack of order – amorphous activity without a coherent structure or system. Chaos. Whereas in reality, those with mental illness exhibit fully formed, consistent systems of thought – they simply aren’t systems we condone, or deem logical. Take, for example, eating disorders: there’s nothing “disordered” about an anorexic’s relationship to food; rather, his or her diet is staggeringly regimented, ordered, and systematic. Mathematics is the ultimate expression of order – a coherent system of thought, deduction, and conclusion. There is no ambiguity in Vincent’s last line, then – “But my beautiful proof lay in ruins” – he is a seeker of structure, and balance.

This paradox is another thing Fasano gets absolutely right in Vincent; a lesser poet might have taken great joy in the liberties we sometimes give to literature of the insane. For cheap thrills, writing a psycho murderer means no rules, no holds barred, no limit to whatever bizarre, chilling antics come to mind. “Mental illness” allows us to write off someone’s entire inner world as incomprehensible; any attempt to get inside his or her head is futile, and empathy is entirely abandoned. Real life offenders like Vincent are easily dehumanized; for we are desperate to retain our belief that human beings aren’t capable of murdering, decapitating, and violating a fellow commuter for no apparent reason.

And this is where Fasano’s poem shows its greatest integrity; he never dehumanizes his protagonist. Fasano may imbue Vincent’s inner life with all sorts of penetrating illness and violence, but the poet never abandons him as beyond empathy. Fasano portrays his murderer with a steady and consistent hand, painstakingly revealing the logic through which Vincent views the world. (Not anything like conventional “logic,” but equally far from chaos and thoughtlessness. Take for example, “I don’t remember the difference / between the solstice and the / equinox but I remember one of them cleans me / and is for doing things like that / which help the system remain.”) This is not to say that Fasano’s account condones, or romanticizes the unconscionable actions of Vincent Weiguang Li – just as Lolita doesn’t condone pedophilia. The poet’s attempt at empathy shouldn’t be mistaken for sentimentality; and Vincent’s howling verse shouldn’t be mistaken for a romp.

As a final note, we must remember that Fasano’s poem is in no way intended as biography, or an accurate depiction of Vincent Li’s childhood. Which begs the questions – what is the poem’s raison d’être as a fictional account of a real person? I like to think that Fasano’s answer comes straight from Vincent’s mouth: “I whispered listen / listen today I read in a place / I cannot tell you of the dark matter / in the cargo of things.” Our protagonist, while a fully formed character, is a vehicle more than anything – a vehicle to explore the “dark matter of things:” “a mare giving birth under the porch / of a blind man’s home,” “the breastmilk / buried in the valleys of the moon,” a landscape overwhelmed by its own emptiness. Comfortless and acute, Fasano’s exploration is well worth reading: a superb effort, and the best thing yet written by a poet whose name we are sure to hear more and more in the coming years.

About PJ Sauerteig

PJ Sauerteig is a recent graduate of Columbia University, where he pursued Creative Writing; his poetry has appeared in Profane Journal, The Columbia Review, Glassworks, 4x4, and elsewhere. PJ is currently studying law at New York University; he also releases music under the moniker, Slow Dakota, and manages a small record label based in Midwest - Massif Records.

One comment