You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

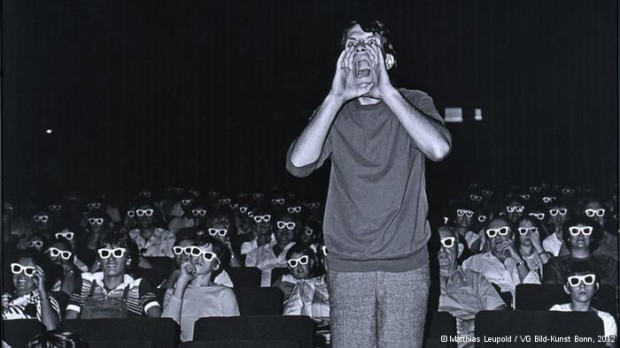

Of all the irritations of the cinema, other people are the worst. A modern cinema audience will chatter, eat, obscure the view, throw litter, snore and confidently make pronouncements on the plot to all and sundry. Friends will shush friends, then giggle. There are people who I know and love and have planned to murder for 90 painful minutes on a weekend, listening to them talk back to the characters on screen, self-censored by a half-whisper, which only goes to show they know that they are doing something forbidden. It’s true: you are.

And yet. On Monday evening I finished work at 6pm and walked along the streets between St Bartholomew’s Hospital and Smithfield Market. The City is a marvel for being both the oldest and the newest area of central London: steel and glass utility crammed improbably on top of medieval foundations, with plenty of alleys, ditches, old churches and guttural names to amplify the paradox. After reaching the old City walls, I climbed the stairs at Barbican tube station and skulked along the empty walkway which runs above Beech Street. The three mighty towers of the Barbican Estate, Le Corbusier’s bastard sons—Cromwell, Shakespeare and Lauderdale—loomed rigidly above me. I felt as though I was on a film set, about to get my head kicked in by a gang of thugs, or at least discover I was being followed by the Stasi.

On this occasion I met two friends at the Barbican’s swish new cinema. When we arrived the foyer was empty. There were two girls in black shirts and skirts wearing colourful sashes with the word INFO written across them. The impressive set-up for screens 2 and 3 of the Barbican arts complex boasts everything people have come to expect from a contemporary art-house cinema: cake and coffee, bold signage, suggestively Swedish plastic furniture, digital projectors and pop-cultural references dotted ironically on the walls and in the toilets. We ate bowls of pasta in a nearby Italian café, then headed back for the £6 Monday evening screening. More people had by now arrived, of all ages and stripes. Nobody seemed entirely comfortable in the building. Its newness left us feeling a little exposed. Where should we stand? What do we do?

We had taken to our red leather seats in the polished auditorium and were waiting for the screen to boot up when one of my companions took out a bag of crunchy popcorn. Horror of horrors. Relax, I thought. This is an indie comedy starring mumblecore sensation Mark Duplass and Parks and Recreation’s Aubrey Plaza: popcorn is OK. Popcorn is good.

And it was. A large part of what makes going to the cinema memorable is the added awareness that comes with sharing your experience with others. Being squashed into a room alongside ten, fifty, one-hundred strangers, is part of the process. There is no such thing as silence when you watch a film like that. In the absence of noise, there lingers the airborne buzz of expectation, the deep breaths of catharsis. With comedy, the pleasure of laughing is partly down to recognising that the lives of others must in some sense resemble your own. People choose their favourite characters, tense up to varying degrees and ooze compassion to the point that the air feels thick before the final credits. I took a handful of popcorn. Though I still relish the freedom to walk into the cinema alone whenever the instinct grabs me, I am glad that, chances are, I won’t be in there on my own.

When the film was over we agreed that it was dumb in parts but pretty decent. A pleasant way to start the week. We said our goodbyes (sad ones, my friends are moving to California this week), and I tried to find a path through the Square Mile in search of Moorgate Station, being constantly re-routed by construction fences which created little lanes and crannies, where the City of the past has been flattened by the demands of—what? Law firms? Accountants? I have no idea.

I took the Northern line south, got off at Oval, stopped to read the day’s mantra on the notice board at the top of the escalator, and headed home. I live in one of the seemingly endless series of early 20th-century tower blocks which spread all over south-east London: erected in a previous period of planned social housing, spurred on by poverty and industrialisation, fifty years before the modernist explosion following the bombs of the Second World War. I walked down a back road past the goods-in entrance of a Tesco supermarket. It was almost midnight. Two men on bikes rode around me like sharks. One lent towards me, forcing me off the pavement onto the road. But there were no cars. Unlike the dead silence of the City, here there is the restless silence of a residential area. I could no longer pretend that I was walking through a film set.

About Philip Maughan

Philip Maughan was born in Middlesbrough in 1987. He currently works at the New Statesman and blogs at philipmaughan.tumblr.com.