You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

There is much to admire in Owen Sheers’s Pink Mist. In this play, Sheers explores the responses of three young men – Arthur, Hads and Taff – to their first tour in Afghanistan. They are accompanied onstage by three women – Arthur and Taff’s girlfriends and Hads’ mother – and through this ensemble of six we are made privy to the physical and emotional consequences of the boys’ decision to enlist.

Pink Mist began life as a radio play. You can hear this straightaway: its form is made for the radio. It is a verse drama, and is littered with rhymes – end rhymes and internal ones. This is affecting for obvious reasons; our ears respond to the patterns in speech, to echoes and lyrical language. There are moments of real poignancy in Sheers’s writing. So, for example, when one of the three main characters is attended to after an accident: “Like two maids making a bed,/ they unfolded, smoothed and checked for snags,/ before draping me in the colours of the flag.” The rhyme is impactful, and the imagery uncomplicated. Elsewhere, we hear about Arthur’s encounter with a man on Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol who “just looked at me, took one long drag,/ stubbed it out, then – ‘He jumped?’, his girlfriend asks. “‘No./ Well, yeah, he did. But more like flew.'” This is where Sheers is at his best: with simple images which rarely miss their mark.

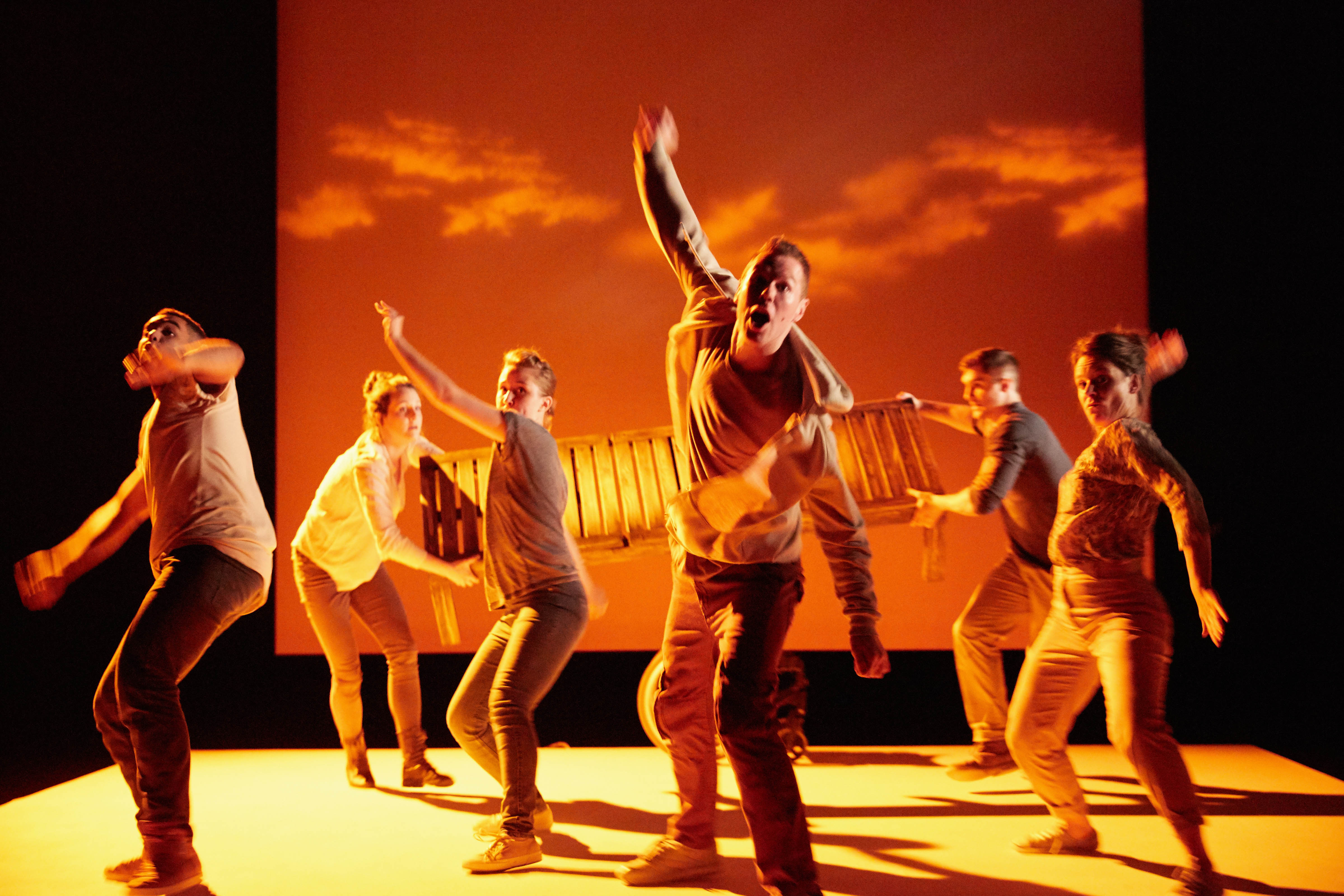

In the Bush Theatre’s current production of Pink Mist, directed by John Retallack and George Mann, the actors work as a slick unit. Their movements are almost mime-like, deliberate and ritualised. Of the six, Phil Dunster as Arthur stands out for the pathos with which he narrates his life-story. His movements are fluid and his mastery of the stage is, at moments, captivating.

Why, then, did I find the blend of the two – the words and the action – occasionally lacking in power? I enjoyed the language, and as I reconsidered the text later I continued to discover elements I admired. But during the performance I found it difficult to forgive the play’s straight narration, the absence of a space for creative enquiry. At times, the production felt stiff as a result of this spoon-feeding, and the incessant rhymes only seemed to compound this formality. Sheers himself highlights this problem in his introduction to the programme, noting that Pink Mist “breaks the cardinal dramatic rule of ‘show don’t tell’… Pure telling… is rarely dramatically engaging and this is where the lyrical note of Pink Mist is vital”. I disagree with this. It is not “the lyrical note” which rescues a formal narrative text from becoming dry and unconvincing – not in contemporary theatre, anyway. It is characters and emotional engagement. This is where the actors might have assisted, bringing life to the voices which narrate the drama. Instead, the actors work as a single body: a dexterous, mesmerising body, yes. But a body nonetheless, robbing the performance of the close character portraits it craves.

I felt especially disengaged from the female characters – largely, I suppose, because they are entirely identified by their relationships with the men. They never address each other. Their every action and emotion is dictated by the decisions of the three male characters. It is a tricky predicament; Pink Mist is, after all, a scrutiny of war, and three young men as victims of that war. But this side-lining of female voices only served to distance me further from the drama.

And then there was the close of the play, which – beyond the too-formal marriage of word and movement, and the absence of autonomous female characters – was its most jarring aspect. The narrative reaches its dramatic climax and continues beyond its natural end in a moralising vein. “That’s all I hope for,” Arthur says, “When the debate’s being had,/ the reasons given,/ that people will remember/ what those three letters mean,/ before starting the chant once more -/ Who wants to play war?” This is the play’s worst (or should that be best?) example of “telling” rather than “showing”, epitomising its lack of faith in the capabilities of its audience. Poetry need not be the “mouth” that Auden pronounces it, making “nothing happen”. But neither, conversely, should it be “a blueprint… an instruction manual… a billboard” (to misemploy the words of Adrienne Rich). I’m glad when poetry and drama engage with questions of ethics, but believe there should be room for excavation. If there is no space for interpretation, the experience of theatre-going or poetry-reading is no longer a dialogue; it becomes an act of submission.

Still, I’d urge you to go and see Pink Mist. Go for the poetry, the blend of the figurative with idiomatic Bristolian language, the epic arc of the three boys’ journey to Afghanistan. Go for the perfectly-timed choreography, the strength and precision of the six actors’ movements. Go for the stunning displays of light and sound. The lasting effect is worth it, even for its moments of disquiet.

Pink Mist continues until Feb 13 at the Bush Theatre. Tickets are £15-£20.

About Xenobe Purvis

Xenobe is a writer and a literary research assistant. Her work has appeared in the Telegraph, City AM, Asian Art Newspaper and So it Goes Magazine, and her first novel is represented by Peters Fraser & Dunlop. She and her sister curate an art and culture website with a Japanese focus: nomikomu.com.